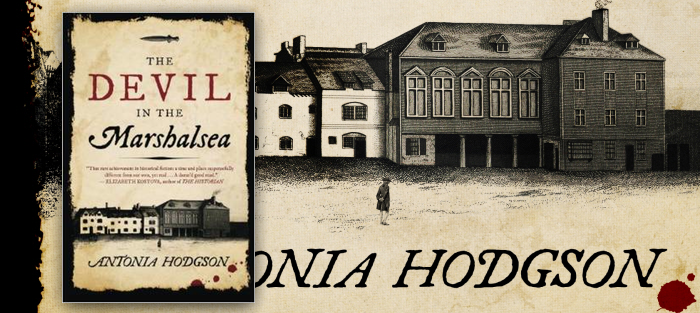

Antonia Hodgson’s debut novel is one of those genre hybrids that may eventually come to define early twenty-first century fiction as a literary period. Genre mash-ups are certainly popular with readers, as Hodgson, the editor-in-chief of Little Brown UK, presumably well knows. Her novel seamlessly blends elements of grizzly horror, mystery-suspense, and well-researched historical fiction.

The Devil in the Marshalsea is anything but a quaint period piece, a costume drama in prose. There are a few well-stuffed, beribboned bodices, but this novel is a grim tale of an eighteenth-century crime (owing money) and punishment (prison for same). The story takes place in 1727 over a four-day period in the life of Tom Hawkins. Imprisoned for a debt of ten pounds, he is desperate to raise enough money to stay alive in the Marshalsea, where everything, including a dormitory room shared with a plague-infected roommate, is sold at premium prices. If Hawkins can find out who killed the prisoner Captain Roberts, he can secure his release before he runs out of money and is tossed over the wall between the higher-class quarters and the horrific Common Side, a move he knows he is unlikely to survive.

As a character, Hawkins could have been lifted straight out of a novel by Daniel Defoe. Like Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, he is a man in need of redemption. During the moments in which he suffers some of the Marshalsea’s most hellish punishments, Hawkins devoutly wishes he had followed a safer, more respectable path. Instead he chose a dissolute life in that most dissolute of capitals, eighteenth-century London, over a secure future as a country parson. The novel provides us with enough introspection and backstory from Hawkins to make him engaging to readers, but not enough to slow the near-frenetic pace of the story.

As a character, Hawkins could have been lifted straight out of a novel by Daniel Defoe. Like Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, he is a man in need of redemption. During the moments in which he suffers some of the Marshalsea’s most hellish punishments, Hawkins devoutly wishes he had followed a safer, more respectable path. Instead he chose a dissolute life in that most dissolute of capitals, eighteenth-century London, over a secure future as a country parson. The novel provides us with enough introspection and backstory from Hawkins to make him engaging to readers, but not enough to slow the near-frenetic pace of the story.

That pacing will be a large component of this novel’s appeal, which is clearly that of a “page turner.” Hodgson combines a sure understanding of the historical period and its customs with a serpentine mystery plot filled with false leads and multiple potential killers–the various devils loose in the Marshalsea. The novel’s sinister prologue sets the story in motion. A murder is committed in the notorious debtor’s prison, and it looks as though the murderers are going to get away clean, except for one small piece of evidence they’ve overlooked. The prologue does not reveal the identity of the victim, but Hodgson skillfully focuses on this piece of evidence, making it a detail the reader is unlikely to forget as the story whipsaws through a handful of days in the life of our hapless hero, days that are lived out in the most terrifying spot in the British Isles.

An almost overwhelming sense of dread is built from the reader’s fear that the dead man will eventually turn out to be Tom Hawkins, our narrator. The way Hodgson works point of view in this novel, the way she controls our identification with Hawkins while persuading us that very bad things are inevitably going to happen to him, is an aspect of horror fiction that she has clearly mastered.

The Tom Hawkins who is first confined in the Marshalsea seems unlikely to survive his ordeal. His judgments are mostly misplaced, and as a result many of his efforts turn out to be misguided. Hawkins’ circumstances, like Crusoe’s, demand that he either change or die. Fortunately, like his eighteenth-century literary forbears, Hawkins is capable of reform. He develops some inner resources and life skills beyond card-playing and fondling loose women. And he proves himself to be a man of courage and honor as well as something of a fool. It’s a matter of which will determine his fate–his virtues or his shortcomings.

Hodgson makes some smart moves in her characterization of Hawkins, giving him as much subjectivity as a character in an eighteenth century novel might have, more than enough to make him engaging to contemporary readers. And if, like many charming, good-looking rakes of the period, Hawkins is not a terribly complex character, another of the Marshalsea’s devils proves to be much more rounded. The bookseller, publisher, and political provocateur Samuel Fleet lives in comfort at the prison, and the other prisoners never tire of referring to the conniving Fleet as the devil. Because he’s imprisoned for sedition rather than debt, Fleet has one of the Marshalsea’s best rooms and offers to share it with Hawkins, who agrees to the arrangement only because he knows the alternative is death by plague. As Hawkins careens through the prison, clumsily trying to find the murderer and suffering the consequences of his ignorance, his relationship with Fleet gradually changes from one of complete mistrust to something resembling friendship. Hawkins’ fate is deeply entwined with Fleet’s. But by the time Hawkins discovers who his true friends are it will be too late for some of them.

The prison warden, William Acton, is also a candidate for the title Devil of the Marshalsea. A well-documented historical figure, Acton springs to life in Hodgson’s novel, a man with absolute power over the lives of the Marshalsea prisoners. The heartless Acton enriches himself by bleeding dry the poor wretches in his grasp. Known to Marshalsea inmates as “the butcher,” he demonstrates his power by whipping a boy to death before the assembled prisoners.

One of Hodgson’s surprising revelations about the Marshalsea, given its unrelenting grimness, is that a couple of its residents are volunteers, and both of them provide romantic interest for Tom Hawkins. The late captain’s widow Mrs. Roberts has paid her off her debts with an inheritance but vows not to leave the Marshalsea until she learns how and why her worthless cad of a husband was murdered, providing, in the meantime, several energetic plot twists. The comely Mrs. Roberts vies for Hawkins’ affections with Kitty, an outspoken serving girl whose father died at the Marshalsea but who, as Fleet’s ward, now has the freedom to come and go as she pleases.

Hodgson’s writing is at its best when describing the prison’s horrors, including the hellish Common Side strong room with its rat-infested corpses. When Hawkins emerges from this place, he’s changed forever: “Some part of what I had seen had been trapped in my eyes, like a fly in amber.” And yet the novel convincingly portrays Hawkins as a man who now stands straighter, emboldened by his survival and outraged on behalf of those who won’t be as lucky.

Part of this novel’s perverse appeal is also the unflinching way it throws open a window on human misery. That Hodgson uses that misery to create a stark sense of dread places her in some interesting literary company. Elizabeth Kostova has written a blurb for The Devil in the Marshalsea. Her best-selling The Historian is a beautifully written novel that evokes a powerful feeling of dread from its first paragraph. Like Kostova, Hodgson demonstrates great skill in establishing the tone and setting for horror. The difference is that the horror Kostova creates is based on a fictional character of near-mythic status. Hodgson relies on imaginative skill to bring to life horrors that are historically verified.

Part of this novel’s perverse appeal is also the unflinching way it throws open a window on human misery. That Hodgson uses that misery to create a stark sense of dread places her in some interesting literary company. Elizabeth Kostova has written a blurb for The Devil in the Marshalsea. Her best-selling The Historian is a beautifully written novel that evokes a powerful feeling of dread from its first paragraph. Like Kostova, Hodgson demonstrates great skill in establishing the tone and setting for horror. The difference is that the horror Kostova creates is based on a fictional character of near-mythic status. Hodgson relies on imaginative skill to bring to life horrors that are historically verified.

The Devil in the Marshalsea will be read compulsively, not just to learn the solution to the mystery, but to discover whether a place like the Marshalsea is survivable by an ordinary, flawed, mostly decent human being. The reader will know dread of a lingering variety as well as, eventually, a feeling of redemptive release. Hodgson may be more Philippa Gregory than Hilary Mantel, but she’s spun a good yarn from a little-explored aspect of eighteenth-century London and gotten her facts straight. Antonia Hodgson’s first novel is a nimble hybrid of genre entertainment and historical realism. She balances elements of mystery, suspense, and horror to produce something the former residents of the Marshalsea would have paid a pretty penny for – an intelligent escape.