P rior to writing his novel The Iron Will of Shoeshine Cats, Hesh Kestin mastered all things non-fiction, serving as European bureau chief of Forbes and war reporter for Newsday before founding two newspapers himself—the Israeli daily The Nation, as well as the prize-winning expatriate, The American. A career crafting leads and managing word counts has shaped Kestin’s fiction in a distinct way: though written richly, it never wastes a cent.

rior to writing his novel The Iron Will of Shoeshine Cats, Hesh Kestin mastered all things non-fiction, serving as European bureau chief of Forbes and war reporter for Newsday before founding two newspapers himself—the Israeli daily The Nation, as well as the prize-winning expatriate, The American. A career crafting leads and managing word counts has shaped Kestin’s fiction in a distinct way: though written richly, it never wastes a cent.

It’s a lesson this young writer’s lavish prose could benefit from, resonating as deeply with me as it does the novel’s protagonist when Kestin, a war-zone wordsmith, channels his unique perspective on “economy” through Shushan “Shoeshine” Cats, the Jewish gangster who takes Iron Will’s hero, Russell Newhouse, under his wing in 1963-era Brooklyn. Shushan sums up much more than Kestin’s past when he tells Russ,

“A general and a poet are exactly the same in one thing. What they do they have to do with critical efficiency. Not a word or an action wasted. And the action has to be more important than the man who creates it.”

This is as much a mission statement for how Iron Will is composed as to how Russ goes about solving the novel’s many crises. Kestin’s journalistic imprint paces the plot into a fluid regiment of short chapters jam-packed with reveals and introductions, all of which—and I mean this, because I actually charted out the turns, ten pages of hand-written notes because the story’s connectedness surprised the hell out of me—come full circle to impact not just Russ or Shushan’s fate, but every character’s and the city that contains them. It’s a no-nonsense approach to storytelling and the joy lies in discovering just how every word and action goes un-wasted. And in the end, Shushan is spot-on: the action that unfolds is indeed more important than the men who create it.

Or, as Kestin might say, the man who wrote it. In a 2009 reading with Dick Heffner, host of public television’s “Open Mind,”Kestin admitted this to his New York City audience: “I’m very often asked, what’s the book about? And I never know what to say because if I could say it in twelve words, I would not have spent 120,000 and a year and a half of my life trying to tell the story.”

Like Shushan, Kestin grew up in the Brooklyn of the 1950s and ‘60s. He knows the time period, and as a Jew, understands how it affected his people. More importantly, he knows how crime—organized, and, as Shushan puts it, “disorganized”—shaped the borough and its residents. The impregnation of Kestin’s past into Iron Will illuminates the author’s comments in a column for The Millions in which the author decried the state of new fiction, saying the following:

“Most new writing suffers from what can only be called peanuts envy, a wish to emulate the classic New Yorker story about uninteresting people with irritating little problems doing little or nothing about them but bumping into similarly boring people doing, if possible, less – and all of it slowly.”

Kestin’s Iron Will is a response to the shortcomings he describes above, stories he has punished physically, admitting, “For years I’ve had the extreme displeasure of throwing new fiction across the room. Launched just right, the spine splits and…pages shake out like, well, bad fiction: unconnected, insubstantial, rank.” Kestin attacks the shortcomings of boring, uninteresting characters by creating the opposite: connected in surprising ways and engaged in action constantly, Iron Will’s cast becomes more than simply colorful, it develops depth. By populating his story with gangsters and bookies from seemingly every New York City neighborhood, with strong-men, crooked cops and even JFK, some detractors of new fiction might think Kestin exchanges one problem for another—by attempting to write work that moves beyond character, he loses character. But that is not the case here. Beyond their looks or lines of work or historical significance, these characters are interesting because of their motivations, as devoted to one another as to a set of ideals or simply the ideal of survival. None of these characters has what can be called a little problem, and, as such, they go about solving them with incredible gusto, all of it developing fast and furious. Kestin has, in ways, written his first novel the only way he could: he has written something he would want to read.

Perhaps this is because the story in Iron Will is one Kestin himself wishes he could have experienced. For me, a new writer torn between industry expectations of success—to say nothing of family, friends and self—and my own unique need to simply express, this realization was liberating. The setting, characters, and plot—bricks that instead of forming foundation so often weigh upon a young writer’s sense of story, the result of which is a deflating heaviness that I sometimes call duty but you might know better as a reader’s expectation—are developed in Iron Will with “critical efficiency,” an exacting journalistic authenticity. But Kestin’s reliance on the tools of his trade does not make his work laborious. While we cannot know for sure if the writing was fun, if it was a joy to immerse himself in this world, we can say with some certainty that Kestin wrote the only way he could: by being himself. And it is this authenticity in the work that makes it a joy for readers to immerse themselves.

Likewise, the intersection of the “real” and the “imagined”—what Kestin has lived versus what could have been lived—shines on every page of the novel, including its cover; Kestin is, after all, the face readers see on its front. This overlap of reality and fiction gives the novel the multi-layered feeling of a palimpsest. When asked to reflect on his creation at the aforementioned reading, Kestin said:

“All I know is that when I finished writing the book, I realized that the child, twenty years old, in question, was me. But the story, of course, had never happened. And I finished half a bottle of whiskey after that. Because I realized that although I had gotten into trouble at twenty, and eighteen, and sixteen, and twenty-one, and twenty-two, I had never gotten into this kind of trouble. And I wondered if I had been man enough to handle it the way this young man did. To this day I’m not sure.”

The “trouble” Kestin alludes to is in continuous evolution during the course of Iron Will’s forty-seven chapters—every new character introduction and subsequent re-entrance brings with it some fresh factoid of Shushan and Russ’s past, a hint at their future, how these things connect. In fact, “trouble” becomes Iron Will’s spine. The turns and twists that occur throughout the book fuse its narrative with milestones built on revelations, every one of them fundamentally shifting the direction and scope of Kestin’s story, a sinfully fun read not just because Kestin is a master storyteller from his journalistic days, or because he knows Brooklyn from his childhood, but because his characters are fun and flawed, and allowed to show us why.

Take, for example, the novel’s namesake, Shushan “Shoeshine” Cats. A fearsome gangster despite his diminutive 5’7” stature, a man who might “…gain weight on a diet of grubs and water,” Shushan is more than just a thug, he is a thinker. Routinely quoting La Rochefoucauld to cops and musing on the seventeen accents and dialects in Huckleberry Finn reveals him as a man as self-educated in literature and art as trained with a rifle and fists.

The Soldiers' and Sailors' Memorial Arch at Grand Army Plaza in Brooklyn / photo credit Jeffrey O. Gustafson from Wikimedia Commons

Now, in a world post Tony Soprano, the gangster in touch with his feelings might not appear particularly original. Yet Kestin ensures Shushan isn’t too good to be true—a rabbi with a rap sheet—by making him painfully dogmatic on nearly every stance and subject. For a shortish man of Jewish heritage like myself, this ensures Shushan remains memorable without becoming a role-model. You come to respect the man for his black-and-white thinking, but fear him for the blood red that might come for foraying into the wrong. Shushan’s traits may be best encapsulated by his mother, a character we never meet but whose impact is clear when Shushan explains that it is she who taught him that if he is punched, he must punch back ten times. And in a perfect example of the duality of this character, he crafts a beautiful eulogy after her death, but insists that Russ read the speech because he can’t let people see him cry. After all, that would be bad for business.

Literature, poetry and music compete with gangster business-theory as constant forces in Iron Will, explored as often through Russ and his English professor as Shushan himself. These discourses on art and law and racism aren’t written to portray Shushan to the reader as some new evolution of gangster; rather, they illustrate how Shoeshine’s intelligence is as important to why he is revered and respected as to why he is feared. We end up believing in Shushan because he tells us what he believes in; because those beliefs, built as solidly as his physique, are allowed to be wrong, contradictory, flawed. Russ’s intimacy with the gangster gives us a unique vantage point. We come to understand how a man can become as committed to charity as crime, and how this makes that man human.

Language itself is a central seductive force in Iron Will. While on the surface drawing lines in the Brooklyn Babel-like war for turf—American streets fought over by decedents of China, Puerto Rico, Africa, and, of course, it being a book about crime, Italy—it is also one of the main reasons Shushan is able to seduce Russ, a devotee to reading and literature, into apprenticeship. The two bond over words and from there on, even when Shushan is absent, literature factors in how Russ solves problems and perceives the events around him in spite of the fact that he believes those old written worlds are no longer part of him:

…books, which had been all, were now merely a pleasant memory, a backdrop, a frame of reference. My adventures in literature could not hold a candle to my adventures in Little Italy, in Chinatown, at the Westbury. Whether purposely or not, I had to read to experience the world through the eyes of others. I was now experiencing it through my own, to say nothing of the other parts of my anatomy.

In the end, Iron Will isn’t about denial, it’s about confrontation. The confrontation of a Jewish people against the hardships they faced in World War II—“In melting-pot America [Jews] were heat-resistant, tempered by several thousand years of being close to, if not in, history’s fires”—just as it is about the confrontation and hardships that Black communities were enduring in Alabama—”‘I’m calling on you to do something about what’s happening to your people…Let me put it to you straight, Mr. Royce. Either you march for your people or you march against them.'” It’s about the confrontation of Russ against his sexaholic past, his orphan present, his open-book future. It’s about the confrontation of law men and criminals, gangster and gangsters, the right way of doing business and the wrong way of doing business. In the end, Iron Will becomes not simply a confrontation of a boy against his past and future, but a borough and country’s:

The ethos of the time was this: our failure—a nation’s, a group’s, an individual’s—was rooted in our own weakness or greed or lust or love or even in our genes. We could not blame someone else: we were our own enemy.

And yet, for such a perfectly tailored story, Iron Will sometimes veers toward too perfect. After all, there is something beautiful about a loose knot, and Kestin, who does such a fine job tying together his characters and twists, may leave some readers almost melancholy that their futures end so buttoned up. Still, if this book’s single flaw is that it it’s almost flawless structurally…well, let’s just say that’s a problem I’d happily embrace in my own work. Consider the multitudes of stories written about gangsters and it’s fair to say the world of new fiction is lucky to count Kestin in its ranks. Here is a writer who knows how to follow his own advice, to write work that matters, and to craft it not in floral prose but literary iron—forty-seven jabs, not a word or action wasted.

Further Links and Reading:

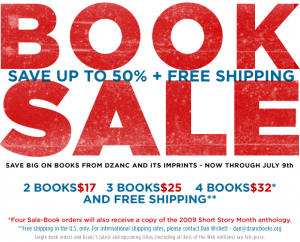

If you’d like to purchase a copy of The Iron Will of Shoeshine Cats, now is the perfect time to do it because Dzanc Books is having a huge summer book sale. From now until July 9th you’ll get half-off their titles plus free shipping. Help support this great non-profit by taking advantage of this equally great deal.

If you’d like to purchase a copy of The Iron Will of Shoeshine Cats, now is the perfect time to do it because Dzanc Books is having a huge summer book sale. From now until July 9th you’ll get half-off their titles plus free shipping. Help support this great non-profit by taking advantage of this equally great deal.

- To read a selection from Kestin’s novel, here is an excerpt from The Iron Will of Shoeshine Cats, published in The Collagist.

- You can also read about how Kestin came to writing in a brief piece he wrote for the Three Guys, One Book blog in their “When We Fell in Love” section, entitled “Books–and Walks–that Made me a Writer.”

- Other authors who’ve recently written on this topic for the “When We Fell in Love” series on Three Guys, One Book include Eric Puchner (Music Through the Floor) , Elwood Reid (DB), Tom Rachman (The Imperfectionists), and Leslie Jamison (The Gin Closet).

Kestin is also the author of Based on a True Story, a collection of novellas. Here is a description of the book from the publisher: “Set on the eve of WWII in an erotically charged Africa, an intensely un-Gauguinesque Polynesia, and a Hollywood of explosive racial and gender identities, the three novella that make up Based on a True Story reveal the roots of contemporary life in a world at war with itself.” This book was published by Dzanc in 2008.

Kestin is also the author of Based on a True Story, a collection of novellas. Here is a description of the book from the publisher: “Set on the eve of WWII in an erotically charged Africa, an intensely un-Gauguinesque Polynesia, and a Hollywood of explosive racial and gender identities, the three novella that make up Based on a True Story reveal the roots of contemporary life in a world at war with itself.” This book was published by Dzanc in 2008.