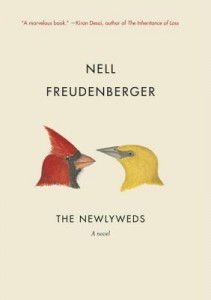

The cover of Nell Freudenberger’s third book, The Newlyweds, is clean and simple. The heads of two birds, a red cardinal and a yellow finch, realistically drawn, face each other on a cream background. This is in contrast to the flashy designs of her first two books, the story collection Lucky Girls, and the novel The Dissident. The relatively simplicity of the cover matches the quiet tone of much of the book. Amina, a Bangladeshi woman in her early twenties, has just arrived in the United States to marry George, an electrical engineer in Rochester, New York. Amina and George meet online, he comes to Desh to meet her parents, and after she is granted a visa, in a nerve-wracking application process, she leaves her family and begins the long journey of becoming an American citizen with the plan, not fully expressed to George for some time, of bringing her parents over to America as well.

The cover of Nell Freudenberger’s third book, The Newlyweds, is clean and simple. The heads of two birds, a red cardinal and a yellow finch, realistically drawn, face each other on a cream background. This is in contrast to the flashy designs of her first two books, the story collection Lucky Girls, and the novel The Dissident. The relatively simplicity of the cover matches the quiet tone of much of the book. Amina, a Bangladeshi woman in her early twenties, has just arrived in the United States to marry George, an electrical engineer in Rochester, New York. Amina and George meet online, he comes to Desh to meet her parents, and after she is granted a visa, in a nerve-wracking application process, she leaves her family and begins the long journey of becoming an American citizen with the plan, not fully expressed to George for some time, of bringing her parents over to America as well.

The story opens as Amina attempts to settle into George’s house. Before coming to the US she slept in a bed with her mother every night. Her father slept on a separate cot in the same room. The scenes that focus on Amina staring out the windows of the suburban house in winter are intercut with her memories of Bangladesh, and the contrast highlights the hush of her loneliness, and the strangeness of her new life.

When Amina returns to Desh to escort her parents through the post-9/11 visa circus, she recognizes in her relatives’ questions about America her own previous fantasies of that life. When she disagrees with George, he often ducks the argument by sighing, “cultural differences…” as an excuse, and it would be easy to read that gap of understanding as the novel’s chief concern. In fact, it is a novel about imagination: how it can fail us, or mislead us, color our self image.

The fantasy of America looms large around the globe: a land of opportunity, a fresh start, a bully, an enigma, a screen for projected desires. It is striking that Amina, the devoted daughter and dutiful wife, who nurtured her American dreams for years, has many difficulties with empathy. For her, imagination ends at other people’s inner lives. Freudenberger makes her so sympathetic that we don’t recognize Amina’s blindness until late in the novel, when she embarrasses a family friend, Nasir. Some disconnects do arise from cultural misunderstandings, but these resolve quickly—Amina is smart. In many ways this is less a novel about learning to become an American than learning to become an adult.

Amina’s parents prepared their only child for achievement, and when the family falls on hard times in Bangladesh, she willingly assumes the savior’s mantle. She worries about convincing George to help bring her parents to America, about her part-time jobs, and about money. She endures sex, George’s family, and George, but although she takes on these adult responsibilities, in many ways her thinking remains childish. She never really second-guesses her decision to leave Bangladesh. She finds it difficult to question the life she has chosen. George and Nasir and Amina’s parents all have secrets, and somehow in her resentment over these secrets, Amina forgets that she has her own. Freudenberger writes,

As a girl she’d often imagined a sort of magic that could give her a glimpse of the person she would one day marry. The likelihood that he existed somewhere made this fantasy even more irresistible, and she could spend hours daydreaming about it in the opulent apartments of her students, waiting for them to arrive at the solutions to simple problems. How thrilled she would’ve been if she’d been able to see George then: a man already, hardworking and reliable, decent looking if not overly handsome, sitting at a computer in an American office. The desire to be sixteen again was suddenly so powerful that a sound escaped her, something between a gasp and a groan.

Culture does not define this scene; such youthful longings are universal. It’s familiar to daisy pluckers the world over—loves me, loves me not. Both family circumstance and her image of America-as-promised-land hobble Amina’s desires—a fact so painful it elicits that gasp. It’s better to be sixteen, dreaming of being twenty-five, than the other way around. Marriage ties Amina to George, but not exactly as she expects, and she imagines herself, as so many people do, into the life she thinks she ought to have, which isn’t necessarily the life she wants.

Amina’s trouble with imagination extends to George’s cousin, Kim. The black sheep of the family, Kim is Amina’s opposite: the not-dutiful daughter. Kim married (briefly) an Indian man and spent time in India, so she expects to click with Amina, since Bangladesh is India’s neighbor. Their interactions reveal unflattering truths—that even well-traveled Americans can assume homogeneity across huge swaths of the globe. Dhaka and Bombay are, of course, miles apart geographically and culturally. But Kim also embodies an American optimism and empathy, traits Amina overlooks.

If this novel has a flaw, it’s in the flatness of many of the secondary characters. I was annoyed by the portrayal of George early on until I realized that he is two-dimensional to the reader because he is still two–dimensional to Amina. He represents her idea of an American husband, not a person. Still, he doesn’t grow much on the page as the novel advances, and Freudenberger relies too much on Amina as an unreliable narrator. When she honestly can’t see a facet of a character’s personality that’s one thing, but withheld information frequently appears with this as an excuse.

Freudenberger’s writing is often described as “witty” or “sly” and though parts of the novel display humor, in contrast to Lucky Girls this book is incredibly earnest. While the first half feels measured, slow even, the building wave of problems and misunderstandings that befall Amina’s family at the end of the novel kept me turning the pages impatiently, and finally brought me to tears. The Newlyweds delivers both a cautionary tale about the failure of imagination, and a monument to its power. It argues that in a country built by immigrants, and fueled by dreams, only the difficult work of understanding each other can save us.