If you are what you eat, what happens when someone else eats what you are?

If you are what you eat, what happens when someone else eats what you are?

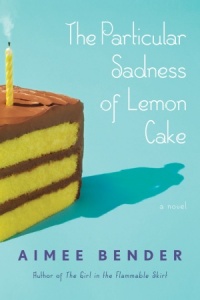

In The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake, 9-year old Rose first experiences this conundrum when she tastes her mother’s birthday cake, only to come away with the uncomfortable understanding of her mother’s lonely dissatisfaction with her life. The cake betrays the inner feelings of the cook. Over the course of the novel and Rose’s life, the predicament continues, building to an unwanted fixation of what constitutes food and those who make it, from the factories and farms to the lives and longings of the preparers.

In one humorous episode early in the book, Rose goes to the bakery with her grumbling kid-genius older brother Joseph and his winningly considerate friend George. There, they set up a series of food “experiments” for Rose. One of the guys working behind the counter offers Rose his sandwich, made by his girlfriend, as a kind of test, which Rose unwittingly passes: “The sandwich was yelling at me to love it. The yelling was loud, and it was too much information to sort through, and it was way too much for nine years old.” By the time Rose hits her mid-20s, the slightly whimsical conceit of being a “food psychic” has taken on all the qualities of a mythical curse.

Throughout, Rose remains a highly sympathetic narrator. As literary foils, Joseph is distant, guarded and aloof; her harmless father, somewhat hapless; her mother, unhappy. Rose’s matter-of-fact acceptance of her unwanted power and brewing family tensions positions her as something of a dramatic hero. She never pities herself. Her largely misunderstood attempts to explain the food problem are understated rather than melodramatic. Rather than see herself as victimized or put-upon, even as a kid, Rose’s affliction only compounds her intricate sense of compassion. Contrary to tenets of Milton doctrine, knowledge here does not corrupt innocence.

Aimee Bender / Photo credit: Philip Channing (from http://college.usc.edu/)

Aimee Bender mixes hyper-realism with magical realism like no other contemporary fiction writer. Experimental in style, her prose has always combined incendiary qualities (The Girl in the Flammable Skirt) with the painstakingly mundane. The laws of the world in Particular Sadness allow for certain fantastic elements, the ability to sense feeling from food, among others, while still imparting everything else pretty much as is, in language as efficient as it is poignant. The words on the page, despite their appetitive subjects, sometimes appear to be starving. The sentences are on a low-fat diet, making their impact all the more surprising. A smack in the stomach.

Bender’s dialogue, stripped of both quotation marks and em-dashes, is as clean as licked plate:

I went to walk by myself at the railing. The ocean looked specific and granular in the high heat. When we reached the very end of the pier, I stood by a short old Japanese fisherman who told me he had been there reeling up the mackerel since six-thirty in the morning. What time did you get up? He asked me.

Seven, I said.

I was already here, he said, looking at his watch. A full bucket of fish nestled at his feet, in a cooler. It was three-thirty. I’m still here, he said.

Now I’m here too, I said.

The elements of the novel are straightforward: the plot is told in three parts; the characters are clearly defined, and they deepen as the protagonist ages; the setting is an ironically lush and light-filled Southern California. Words can be visceral this way, ingredients blended into sentences that make us sigh or ache. But true to title, the world of this narrative is highly particular and overwhelmingly, consistently sad. More bitter than sweet. So much so, at times, that you find yourself thirsting for a reprieve, a prosaic palate cleanser. And while much in conveyed is sadness, the novel’s accomplishment and its shortcoming lie in the suspension of disbelief, the conceit required by the reader to allow a work of fiction to feel like something real.

It is to Bender’s credit that Rose’s trials feel somewhat universal for a character whose supernatural power quickly gives way to dark revelations. That the slender book packs such an emotional wallop in such tight space makes the narrative almost suffocating at times, reflective of Rose’s own situation.

In the final third of the book, the narrative pivots on the idea that these supernatural powers are more common than you’d think. And the question becomes not whether or not you have them but whether or not you use them for good or let them destroy you. In the act of telling, the novel seems to say, you can parcel out some of the loneliness that makes you as an individual strange and drop it back in the vat of communal disappointment. The characters most at risk in this story are those for whom their gift becomes their undoing or who are too afraid to fully understand it. It is a fragile world, with much suffering to swallow. So much unknown and more information than we can process. But in small bites, it can offer perspective, hark back to seeding and growth, a spot of earth, somewhere with good light and soft soil.

Like the food Rose intuits, the process of reading itself acts as comfort, provides sustenance, suggests inner workings of lives that are not our own. But because the properties of this world are so specialized, and because the prose is so tight, the distance between the character and the reader is actually greater than one might think given the accessibility of the prose. You are always aware that Rose is not you, and for this you are grateful. But it also takes away something from the story, when you are ever reminded that this could never happen. It dilutes the effect and creates a narrative distance that at times feels almost impenetrable.

What becomes heartbreakingly clear is that we never really want to know the inner selves of those closest to us, that the guises and masks donned for the benefit of others belong there, and when what is hidden reveals itself, the information transmitted can be awful or funny, sad or heartening.

Food, like sex or sleep, invites symbolic characteristics, something to decode and attach meaning to. To dress up, deconstruct, or simplify. We steal its vocabulary all the time, a delicious chill in the air, a salty attitude, a sour demeanor. In some ways it is our most evocative sense, and yet we don’t give it the psychological credibility of say, smell.

Recently, psychologists have released new information about supertasters, people whose taste buds are so sensitive that when a taste is slightly unappealing, they feel the need to scrape off their tongue. That is what the book is closest to—a highly sensitive and vulnerable state that you almost want to give back, but for the fact that so much is imparted, so much to savor:

My soup arrived. Crusted with cheese, golden at the edges. The waiter placed it carefully in front of me, and I broke through the top layer with my spoon and filled it with warm, oniony broth, catching bits of soaked bread. The smell took over the table, a warmingness. And because circumstances rarely match, and one afternoon can be a patchwork of both joy and horror, the taste of the soup washed through me. Warm, kind, focused, whole. It was easily, without question, the best soup I had ever had, made by a chef who found true refuge in cooking. I sank into it.

Much is made about food these days. Where it’s grown, how it’s harvested, if people are getting enough or too much. We have eating champions and cooking channels and reality television that employ food as a kind of showdown. A platform for machismo or decorum or flourish. But all of these things make taste secondary, if not all together expendable. And it seems that by remembering that food is supposed to be nourishing, it is also simply to say that food, like story-telling, is part of what makes us human.

Further Links and Resources

– Via NPR, read an excerpt from The Particular Sadness of Lemon Cake.

– Read (and watch) Aimee Bender’s story “Hotel Rot”.

– Random House’s Bender site offers “The Rememberer,” a story from the author’s debut collection, The Girl in the Flammable Skirt.

– This relatively new Bender story, “On a Saturday Afternoon,” is published in Nerve.

– Here are some interviews with Bender: with Dave Weich at Powells.com; with student Michael Campos on USC’s website; with Ilana Simons at BN’s Unabashedly Bookish; with Amy Myerson at Fanzine.

– See what books have blown Aimee Bender’s mind: