Steven Wright, a stand-up comic known for his droll, deadpan delivery, and for finding humor in taking the figurative literally, has a joke about naming his dog Stay and getting a sadistic kick out of training him to come.

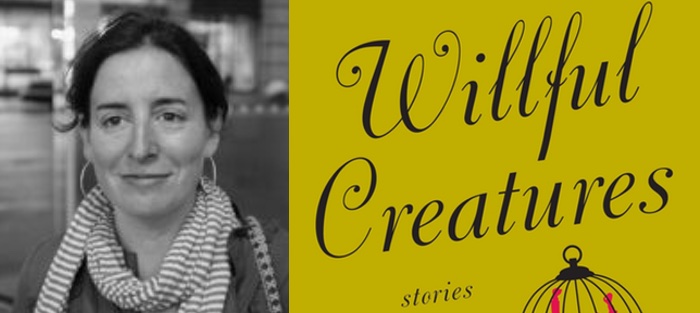

Aimee Bender’s short story “Off,” from her 2005 collection Willful Creatures, takes a similar premise as the title. The main character and narrator, who once had a Great Dane she named Off to mess with people at the dog park, is an insecure, angry, lonely, orphaned heiress who tries to take a casual party by storm. She arrives overdressed, fashionably late, and with the self-declared goal in the first sentence to kiss three men, each with a different hair color. If, as Charles Baxter claims in The Art of Subtext, scenes in fiction are the staging of desire, then “Off” is one long scene. The party is the stage where the narrator self-destructs, her superficial desire drives her to create a scene because, ultimately, she wants to be seen, to be loved. Such is her craving that when her art teacher had failed to notice the menace in her landscapes, failed to see the knives she painted into the cornfields and the loaded machine gun on the beach, the narrator—wielding the influence her inheritance has given her—had the teacher fired. She wants to be seen but seen for who she really is. Not simply a sexy, wealthy socialite but a complex, suffering human being.

Aimee Bender’s short story “Off,” from her 2005 collection Willful Creatures, takes a similar premise as the title. The main character and narrator, who once had a Great Dane she named Off to mess with people at the dog park, is an insecure, angry, lonely, orphaned heiress who tries to take a casual party by storm. She arrives overdressed, fashionably late, and with the self-declared goal in the first sentence to kiss three men, each with a different hair color. If, as Charles Baxter claims in The Art of Subtext, scenes in fiction are the staging of desire, then “Off” is one long scene. The party is the stage where the narrator self-destructs, her superficial desire drives her to create a scene because, ultimately, she wants to be seen, to be loved. Such is her craving that when her art teacher had failed to notice the menace in her landscapes, failed to see the knives she painted into the cornfields and the loaded machine gun on the beach, the narrator—wielding the influence her inheritance has given her—had the teacher fired. She wants to be seen but seen for who she really is. Not simply a sexy, wealthy socialite but a complex, suffering human being.

Bender expertly dramatizes the neediness and insecurity of her narrator via an irresistibly bitter voice that is simultaneously wounded and entitled, intelligent and articulate yet totally deluded. Well, perhaps not totally. Moments of genuine understanding break through her armor. One such realization occurs while she is assessing the couples at the party:

I stand alone because I plan on making all these women jealous, reminding them how incredible it is to be single instead of always being with the same old same old except tonight I am jealous too because all their men are seeming particularly tall and kind on this foggy wintery night and one is wearing a shirt a boyfriend of mine used to own with that nubby terry-cloth material recycled from soda cans and it smells clean from where I’m standing, ten feet away, and it’s not a good sign when something like a particular laundry detergent can just like that undo you.

All it takes is a whiff of detergent to undermine who she thinks she is, the image she is trying to project, bringing her loneliness home to her.

The narrator’s goal—making out with three men—may be a conquest of self-affirmation or a distraction from the lonely, unloved feeling that is simmering just beneath the surface. Her motives, like any compelling character’s, are complex and partially obscure, to reader and character alike. Bender excels at leaning into these unknowns and unknowables. In her essay on character motivation in The Writer’s Notebook: Craft Essays from Tin House, she cautions writers against oversimplifying their character’s psychology and argues against thinking of human desire in a simple “one-to-one ratio of motivation to action.” She worries that boiling down a character’s psychology to one clear motive “reduces fiction and reduces the human mind. It also demeans the character.” Her pitch for complexity and nuance goes right to the heart of what makes great fiction.

But that doesn’t prevent us from trying to figure this narrator out, to understand her desire. Or perhaps more than desire, this story is a staging of dread. She dreads being doomed to a life of never being seen or loved. Or, to quote Raymond Carver’s final poem “Late Fragment”:

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

The narrator of “Off” dreads not being able to say the same. And this dread feeds into all that she does at the party.

The quest for the three men, as readers might guess from the outset, doesn’t go well. The first, the redhead, laughs in her face after they kiss. It turns out they went to grade school together. His laughter and the fact that he remembers something she doesn’t, unsettles her, undermines her control, and she retreats back to the main room in the party, her darkening mood reflected in the food on the table: “the guacamole dip is at half, and there are little shit-green blobs on the tablecloth. The brie is a white cave. The wine-glasses are empty except for that one undrinkable red spot at the bottom.”

The next conquest, Adam, the blond, is a man she used to date. But the danger here is that Adam may have actually cared for her, may still care for her. They kiss and keep kissing until she feels some former feeling for him resurface. She rejects the feelings and him. This inner conflict, desiring love, dreading remaining unloved, yet not feeing worthy of love, not knowing how to love, saves the narrator from coming off as a sadistic snob. The memory of her dog Off displays her contradictions. She loved calling Off over at the dog park to confuse not the dog but the other people there watching her, a strange young woman in fancy dresses sending conflicting messages. But the memory also reveals her inner stores of tenderness: “Off died early because he was a purebred but I didn’t put him to sleep, I kept him company and stroked his big forehead until I saw his eyes shut on their own.”

Failing in her quest for the third and final man, she heads to the bedroom and creates a scene by stealing all of the other guests’ coats. A cry for help in the form of a lonely young woman in a fancy dress hiding under a pile of coats in a closet. People come looking for their coats eventually but find nothing cute in the prank. Instead, she feels even more alone. She feigns drunkenness but Adam sees her. Adam knows she isn’t drunk. This same Adam who took one look at her paintings and saw the pain in them. The story ends with Adam taking her hand and though the character is too complex for us to predict with any certainty what comes next, I think Bender would forgive her readers for inferring that, this time, she doesn’t take it back.