Since the start of the pandemic, I’ve been teaching introduction to creative writing classes online using Canvas, a learning management system. I have each week of the course set up as a separate module covering a craft topic, say, point of view or setting. But my transitions between genres are abrupt and clumsy. I’m looking for ways to segue from nonfiction to fiction more smoothly than saying “that’s a wrap, folks,” and clicking on the next module with exaggerated finality.

Recently, I think I may have found such a segue in the similarities across first-person perspective in personal essays, memoir, and short works of fiction. Across genres, I’m drawn to works that often have both a strong then voice, a clear I in the scenes, the narrator as a character acting in the world, interacting with it—and an equally strong now voice, the voice of the essayist’s persona or fictional narrator reflecting on the events, sifting and sorting through the layers of meaning that the passing of time has revealed.

In his craft book on literary nonfiction, To Show and To Tell, essayist Phillip Lopate argues for this double perspective as being essential to the memoir. The trick, he claims:

. . . is to establish a double perspective that will allow the reader to participate vicariously in the experience as it was lived (the child’s confusions and misapprehensions, say), while benefiting from the sophisticated wisdom of the author’s adult self. This second perspective, which takes advantage of a more mature intelligence to interpret the past, is not merely an obligation but a privilege and an opportunity.

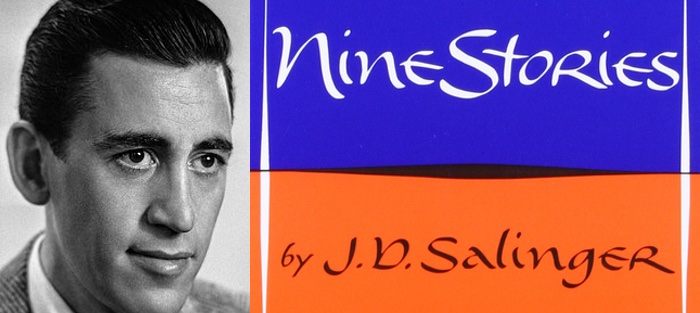

One story that seems to seize this opportunity especially well is J.D. Salinger’s “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period,” from his classic collection Nine Stories. Lopate says that this double perspective is useful in the opening of an essay or memoir, as a way to orient the reader. Salinger does just this, beginning with a dedication to the narrator’s stepfather, who he writes was “an adventurous, extremely magnetic, and generous man.” But then, in the following parenthetical sentence, also introduces us to the differences between who the narrator is now, thirteen years later, and his younger self: “After having spent so many years laboriously begrudging him those picaresque adjectives, I feel like it’s a matter of life and death to get them in here.” Clearly, the narrator’s appreciation of his stepfather can only be understood and articulated in retrospect.

The narrator, last name possibly Smith, then lays the groundwork for the rest of the story. His mother has just passed. And after spending his teen years, nearly a decade, in Paris, he and his stepfather move back to New York. This combination of the loss of his mother and his adopted culture add to the already volatile mix of early adulthood and precipitate a crisis. But I think it may be Salinger’s use of double perspective throughout the story, as a way to provide context and to poke fun at the self-serious young man, that wins the reader over. Even the characterization is filtered through Smith’s older, wiser perspective as when he’s fuming over a slight on a crowded New York bus: “at nineteen, I was a hatless type, with a flat, black, not particularly clean, Continental-type pompadour over a badly broken-out inch of forehead.” In a story brimming with mysticism and featuring not one, but two epiphanies, this older, wiser voice adds a welcome levity. The reader is on the bus with a young Smith frustrated and full of grief but also rooting for him because his story is filtered through an older, wiser, self-deprecating version of himself.

The narrator, last name possibly Smith, then lays the groundwork for the rest of the story. His mother has just passed. And after spending his teen years, nearly a decade, in Paris, he and his stepfather move back to New York. This combination of the loss of his mother and his adopted culture add to the already volatile mix of early adulthood and precipitate a crisis. But I think it may be Salinger’s use of double perspective throughout the story, as a way to provide context and to poke fun at the self-serious young man, that wins the reader over. Even the characterization is filtered through Smith’s older, wiser perspective as when he’s fuming over a slight on a crowded New York bus: “at nineteen, I was a hatless type, with a flat, black, not particularly clean, Continental-type pompadour over a badly broken-out inch of forehead.” In a story brimming with mysticism and featuring not one, but two epiphanies, this older, wiser voice adds a welcome levity. The reader is on the bus with a young Smith frustrated and full of grief but also rooting for him because his story is filtered through an older, wiser, self-deprecating version of himself.

The older narrator is constantly poking fun at the younger one, but with affection, admitting “except under pretty rare circumstances, in any crisis, when I was nineteen, my funny bone had the distinction of being the very first part of my body to assume partial or complete paralysis.” There’s no way of knowing how this story may have turned out without this double perspective, though it seems possible that the narrator’s angst and snobbery would have come off as insufferable instead of endearing (as Holden-haters are quick to say about the bumbling protagonist in The Catcher in the Rye).

Longing to escape his loneliness in New York, the escalating tension with his stepfather, and, in effect, himself, Smith applies to a summer gig in Montreal teaching drawing and painting for a correspondence school. In his application Smith remakes himself into Jean de Daumier-Smith, descendant of the renowned artist, friend to Picasso, accomplished painter, and grieving widower. The lies are grandiose, but so is Jean’s self-importance, something the older Smith loves pointing out: “I also enclosed what I thought was a very casual note that only just began to tell the richly human little story of how, quite alone and variously handicapped, in the purest romantic tradition, I had reached the cold, white, isolating summits of my profession.”

Needless to say, Smith—now Jean—doesn’t thrive in his new position in Montreal. The school is a dump. The owners, who are also the only other instructors, are indifferent to Jean no matter how many lies he spins about his dear friend Picasso. His misery swells until he comes across a submission from a new student, a nun named Sister Irma. The sincerity and religious devotion in her application, along with the quality of her work, make an impression on Jean: “After thirteen years, I not only distinctly remember all six of Sister Irma’s samples, but four of them I sometimes think I remember a trifle too distinctly for my own peace of mind.” In this lonely, overwrought state, Jean churns out a letter, or, from the sound of it, a tome, to Sister Irma, gushing about her work, griping about the other students, denigrating the school, and practically inviting himself to the convent for a visit.

He mails his letter and, flush with joy, goes to bed. But older, wiser Smith informs us: “The fact is always obvious much too late, but the most singular difference between happiness and joy is that happiness is a solid and joy is a liquid. Mine started to seep through its container as early as the next morning. . . .” Lopate lives for these reflective moments, “where the writing takes an analytical, interpretative, generalizing turn: they seem to me the dessert, the reward of prose.”

The joy continues to seep out as Jean struggles with pretending to care about his other, talentless, students, while desperately waiting for Sister Irma’s reply. At this low point, his first—and one hopes, false—epiphany strikes:

I stopped on the sidewalk outside the school and looked into the lighted display window of the orthopedic appliances shop. Then something altogether hideous happened. The thought was forced on me that no matter how coolly or sensibly or gracefully I might one day learn to live my life, I would always at best be a visitor in a garden of enamel urinals and bedpans, with a sightless, wooden dummy-deity standing by in a marked-down rupture truss.

Hideous, indeed. This thought, living in a mean, ugly world with an indifferent and sickly god, drives Jean to bed where he lies shivering, trying to focus on Sister Irma, Sister Irma as a beautiful young woman his age, waiting for him to accompany her on a walk through the lush convent gardens.

But his courtship is not to be. An impersonal letter arrives from the Mother Superior of Sister Irma’s convent. Sister Irma will not be able to continue taking her courses. Unforeseen circumstances. Would a refund be possible? Jean, of course, is crushed. Later, alone once more in his room, he writes a second letter to Sister Irma. He begs her to reconsider. Wants to know why she’d decided to stop taking the course. Again, invites himself to the convent to discuss matters further.

Before he has the chance to bombard Sister Irma with another missive, his second, and true, epiphany occurs, once again, outside the providential orthopedic appliance shop. This time, a woman is inside, changing the truss on the dummy/deity. Jean stands outside in his tux creepily watching this work until the woman realizes she’s being watched and, startled, slips and falls. He reaches out to her but his fingers hit the glass of the window. The woman stands, ignores the creep in the street, and gets back to work fixing up the dummy. Then, the epiphany hits:

Suddenly (and I say this, I believe, with all due self-consciousness), the sun came up and sped toward the bridge of my nose at the rate of ninety-three million miles a second. Blinded and very frightened—I had to put my hand on the glass to keep my balance. The thing lasted for no more than a few seconds. When I got my sight back, the girl had gone from the window, leaving behind her a shimmering field of exquisite, twice-blessed, enamel flowers.

Jean—now, perhaps, Smith once more—stumbles down the street, shaken but also revitalized by the insight that follows after he sees the light: “Everybody is a nun.”

Smith’s time in Montreal speeds to an end. The art school shuts down because of a lack of licensing. Smith doesn’t mail Sister Irma his letter. He leaves her to her work. He forgets about the urinals and bedpans and meets up with his stepfather to spend the rest of the summer looking for love on the beaches of Rhode Island.

Smith’s time in Montreal speeds to an end. The art school shuts down because of a lack of licensing. Smith doesn’t mail Sister Irma his letter. He leaves her to her work. He forgets about the urinals and bedpans and meets up with his stepfather to spend the rest of the summer looking for love on the beaches of Rhode Island.

I have mixed feelings about epiphanies in narratives. Yes, they can be clichéd, tired tropes of literary fiction that sometimes result in too-tidy slogans like “everybody is a nun.” But they can also be sincere moments where meaning is revealed to us. Both of Smith’s epiphanies feel like the latter.

But how does Salinger pull it off? A retrospective, reflective narrator isn’t the only storytelling trick he’s employing here: he has a great ear for dialogue and a playful, clever, and compelling voice. Still, I think it’s the double perspective that sucks me in. The framing of the story, the older narrator alternating between tenderness for his younger self and taking wry jabs at his narcissism, even the confessed self-consciousness about his second epiphany, win me over every time I reread the story. Or, to put it simply, the success of young Jean’s story hinges on older Smith telling it.

Star wipe to next module.