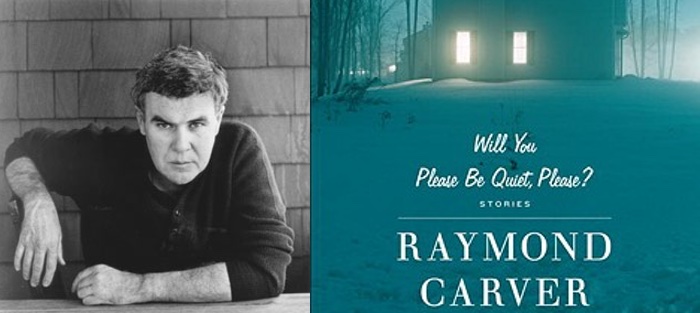

I’m not the type of hypochondriac who tells people I’m sick. Instead, I obsess over my imaginary ailments secretly. When I found myself pawing at my heart while reading Raymond Carver, I thought, “What’s wrong with me? Is it my heart?” Then, I realized it was my reaction to the short story, “Are You a Doctor?” from Carver’s collection, Will You Please Be Quiet, Please? (McGraw-Hill, 1976).

The story itself is about a lonely man, who receives a call from someone dialing the wrong number. After an awkward conversation that moves into friendly small talk, the woman proposes they meet. The man, Arnold Breit, doesn’t initially agree, but eventually, he shows up. What I wondered after reading the story was, what exactly did Carver do to make his character’s isolation so palpable that I felt it physically?

The story itself is about a lonely man, who receives a call from someone dialing the wrong number. After an awkward conversation that moves into friendly small talk, the woman proposes they meet. The man, Arnold Breit, doesn’t initially agree, but eventually, he shows up. What I wondered after reading the story was, what exactly did Carver do to make his character’s isolation so palpable that I felt it physically?

I read it again, line by line—this time, looking for specific moments that increased the tension in the story. The first few pages of the story are almost all dialogue with little exposition or description. Because of this, the moments that aren’t dialogue seem especially memorable. For instance, when Arnold “pulled off his slipper and began massaging his foot, waiting,” the reader is waiting, too. There’s a real silence in this sentence. It’s a literal silence because there’s a pause in the dialogue, so the reader almost hears the quiet of the room as Arnold sits by the telephone, massaging his foot. When he lets go of his foot half a page later, it feels like a real event, because it’s almost the only description outside of dialogue.

Clara Holt, the woman on the phone, asks to meet him. Arnold decides to go to her apartment after looking in the mirror and seeing he still wears his hat. After making this decision, he immediately checks his nails. Why does it matter that Arnold checks his nails? It’s such a private, solitary gesture: people clean their nails alone. One also massages one’s foot alone for that matter. Carver is showing us Arnold in the bathroom, giving the reader his most private self. It makes him seem all the lonelier.

As he climbs the stairs to Clara’s apartment, Arnold remembers his honeymoon in Luxembourg, then “felt a sudden pain in his left side, imagined his heart, imagined his legs folded underneath him.” I didn’t even catch this on my first read, how utterly derivative my heart troubles were. Yet, the moment that got me more than this was when he is again in conversation with Clara once he’s in the apartment. Looking down at his hands, he tells her he must go because he becomes aware of himself “gesturing feebly.” In this moment of awareness, like the moment he is checking his nails or massaging his foot, he may as well be naked. The reader is embarrassed for Arnold. We are embarrassed because we know we would be if we were in his situation—not only to be in this apartment, with someone who called a wrong number—but also, to be caught gesturing feebly in front of Clara.

At the end of the story, Arnold is standing in the middle of his apartment waiting for his phone to stop ringing, a call, he knows, from his wife. As he stands there, “tenderly, he put a hand against his chest and felt, through the layers of his clothes, his beating heart.” The word “tenderly” here gives this sentence its power. At this point in the story, Arnold is so fragile that he has to be careful with himself. Even alone, he must touch himself gently, “tenderly.” And of course, the word “tenderly” has emotional resonance. We feel it along with him.

It is in this state that Arnold eventually answers the phone. His wife lightheartedly teases him, not knowing his fragile state. Because the reader does know it, the wife comes across as cruel. We know too much. Once again, we’re embarrassed to be with Arnold during this private exchange with his wife. He is totally exposed to us as the story ends. My fake heart attack wasn’t because of Arnold, though. It was because Carver exposes the reader, too. Because I recognized Arnold’s isolation and fragility, I knew that it could have been me in that room—on another day, it could be me.