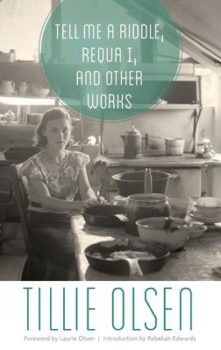

I’m an English instructor at a local college and a literacy specialist at an elementary school. I interact with hundreds of people each week. In summers, I tend to hibernate. This past year, I relished my solitary, quiet summer of reading and writing and dreaded my re-emergence into the world and my real jobs, the ones that pay my mortgage. I read Tillie Olsen’s Tell Me a Riddle, Requa I and Other Works (Bison Books, 2013), right before I had to go back to work. My favorite characters in Olsen’s book are the ones who do what I did that summer: escape. But really, that’s not the right word. It’s a mentally active time, when the mind and heart make sense of the people and the doing of life—the suffering inside and outside of one’s self. During my summer, and in these stories, the mind is where you go to feel safe, to be alone, to gain some sort of “reconciled peace.”

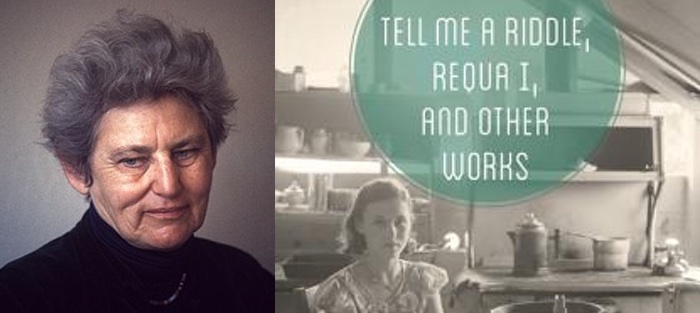

Tillie Olsen’s life sounds like it was exciting, busy, and a little sad as she struggled to balance work, family obligations, political activism and writing. As I read this book, I couldn’t stop thinking about my own escapes into language, and what must have been her escapes as well. Like myself, like Tillie Olsen—Emily and Eva, from “I Stand Here Ironing” and “Tell Me a Riddle”—seek refuge from the world in their vivid, active minds. These characters avoid the sounds and language outside of themselves for that which can only be found within, a place where words and language have no sound, but give meaning to experience, memory, and feeling. Only then, can Emily reemerge into her more public self, or in the case of Eva, let go of it.

Tillie Olsen’s life sounds like it was exciting, busy, and a little sad as she struggled to balance work, family obligations, political activism and writing. As I read this book, I couldn’t stop thinking about my own escapes into language, and what must have been her escapes as well. Like myself, like Tillie Olsen—Emily and Eva, from “I Stand Here Ironing” and “Tell Me a Riddle”—seek refuge from the world in their vivid, active minds. These characters avoid the sounds and language outside of themselves for that which can only be found within, a place where words and language have no sound, but give meaning to experience, memory, and feeling. Only then, can Emily reemerge into her more public self, or in the case of Eva, let go of it.

In “I Stand Here Ironing,” a mother irons while worrying about her nineteen-year-old daughter, Emily. The narrator, going back in time to when Emily is younger, speaks of her “beautiful baby” three times in the first two pages, but then there is no money and the mother is forced to work. Emily’s “shining bubbles of sound” become “a clogged weeping that could not be comforted.” It seems that even as a baby, Emily deals with pain by keeping it inside and seeing what comes of it. The more neglect and tragedy the child endures—evenings home alone to watch the other children, a Sanitorium—the more the child retreats into herself.

Her sister Susan tells “jokes and riddles to company for applause while Emily [sits] silent.” We know Emily has an active mental life. The jokes and riddles Susan tells are hers. Emily compares her mother ironing to Whistler’s mother in her rocker. She transforms herself when she’s on stage performing. From her earliest moments of childhood, Emily has learned to cope with life by turning inward. There is much in Emily that will not bloom, her mother says, but Olsen seems to tell us that what has bloomed in Emily—her active mind and ability to create art—is enough. It has to be.

Emily and Eva, from “Tell Me a Riddle,” have a lot in common. Eva’s son Lennie mourns her as she’s dying not so much for what he is losing, but for “that which in her that never lived.” Sound familiar? Eva has failed to bloom in the same way Emily has.

In this story, Eva has found a peace in her old age after a life of poverty, war and the raising of many children. This peace comes from solitude: her books, the occasional record, and hearing loss. She has a hearing aid, but keeps it turned down to feel more alone, unless she’s listening to her records. Her intellectual life, filled with words from songs and literature from her youth, are private. She doesn’t like to share them with her husband and only plays her records when he is out.

As Eva dies of cancer, she tries to further isolate herself in her daughter’s home, with its loud children and crying baby. “If they would but leave her in the air now stilled of clamor, in the reconciled solitude, to journey on to herself,” she thinks. Eventually, she finds a hiding spot to escape. In the afternoons when the family thinks she’s napping, Eva “hunch[es] in the girls’ closet on the low shelf where the shoes stood.” David, Eva’s husband, remembers his wife from fifty years before, her head shaved and wearing a prison dress, her adoring eyes peering up to him. However, when Eva looks back on those days, she doesn’t think of her husband at all. She only remembers Lisa, the girl who taught her to read. Eva tells her granddaughter that on the day of her death, she will go back to “when she first heard music, a little girl on the road of the village where she was born.”

It isn’t solace Emily and Eva are seeking, but a way to transform their pain. Through war, fear and lack, they transcend it by going inward. Emily relies on her performances and riddles, Eva on her memories of literature and music. These characters do their best in the midst of the hard lives they lead. It’s art that saves them. Art saves me, too, every summer, every evening, every time I close the door of my bedroom, giving my family the signal—now let me be.