In the fall of 2009 I took a job teaching writing at Cameron University in Lawton, Oklahoma. While I’ve lived all over the country, Lawton didn’t resemble any other America I had known up to that point. Of all the differences that contributed to this (weather, geography, politics) the most pronounced was the fact that Lawton is a military town, in particular an Army town. Adjacent to the city is Fort Still, home of the US Army Field Artillery. So entwined are the identities of the city and the base that you often see them hyphenated or slashed (Lawton/Ft. Sill) on everything from road maps to departure boards in airports. But unlike military towns such as San Diego or Annapolis, Lawton just barely has a middle class. It is a poor and often transient city. In the state legislature in Oklahoma City, Lawton is often referred to as “Pothole City,”: at 100,000 residents it is Oklahoma’s fourth largest city, but because it doesn’t have an adequate tax base (military pay is tax-free for Oklahoma residents) it lacks the revenue to support it.

As I came to learn from my students, most of whom where Army brats who’d grown up on bases their entire lives, while Lawton didn’t resemble other places I had lived, it did resemble the other military towns they had lived. Setting the difference between the Navy and the Army aside, I learned that San Diego and Annapolis are essentially the outliers. The more common experience for a stateside military family is to live in one of the various Lawtons of America: Killeen, Texas (Ft. Hood); Fayetteville, North Carolina (Ft. Bragg); Tacoma, Washington (Ft. Lewis), and so on. Everybody—I mean like ninety percent of my students—had some tie with the military: either they were currently serving, or their parents or their spouses were serving, or they were retired. In fact, the only way many of my students could comprehend paying for college was to join the military. And keep in mind, when I first started at Cameron many of the students who were first stepping into my class were themselves just stepping out of war zones.

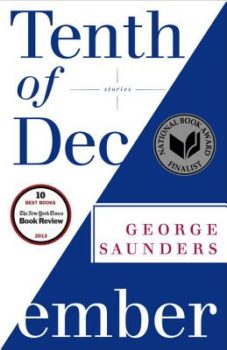

I bring all of this up because I want to try and convey the backdrop for which I came to teach George Saunders’ story “Home.” Saunders’ story collection Tenth of December: Stories was published by Random House in January of 2013 where it shot to #2 on the New York Times bestseller list, an extraordinary achievement for a collection, and how I rationalized teaching it in a 200-level course called “Popular Fiction” that spring. The course usually attracted a few English majors, but mostly the class filled up with students looking to read Steven King and get elective credits along the way. I was apprehensive at first about teaching Saunders because, despite the simplicity of the language and the straight-forward plots, I wondered if he required still a level of literary sophistication. Satire can be complex and it often requires readers to be in tune with a particular off-the-page subtext. I didn’t know that my students had that.

I bring all of this up because I want to try and convey the backdrop for which I came to teach George Saunders’ story “Home.” Saunders’ story collection Tenth of December: Stories was published by Random House in January of 2013 where it shot to #2 on the New York Times bestseller list, an extraordinary achievement for a collection, and how I rationalized teaching it in a 200-level course called “Popular Fiction” that spring. The course usually attracted a few English majors, but mostly the class filled up with students looking to read Steven King and get elective credits along the way. I was apprehensive at first about teaching Saunders because, despite the simplicity of the language and the straight-forward plots, I wondered if he required still a level of literary sophistication. Satire can be complex and it often requires readers to be in tune with a particular off-the-page subtext. I didn’t know that my students had that.

But whatever fears I had of students not getting it were quickly dispelled on the first day of discussion when we looked at two early stories, “Sticks” and “Escape from Spiderhead.” Of the eighteen students who enrolled that spring seven were soldiers: two vets and five active duty. And that day the I heard from over the half the class about what they thought was weird, or funny, or interesting. I talked a little bit about how plot works, how characters are developed, a few wrote some things down in their notebooks. On the second day we read “The Semplica Girls Diaries” and everybody agreed that the story was crazy, but in a good way. I talked a little bit about how a story can depict, in almost real time, what it is like to become aware of something, to gain consciousness. I misspelled “consciousness” on the board and was corrected. Some students wrote some things down in their notebooks.

On our third and last day with the book we got to the story “Home.” In it a soldier, Mikey, returns to America from a war overseas. The America he returns to is absurd and petty and cruel. I wondered, in preparing for the class, if this was going to be too on the nose, if the students would feel provoked or become defensive. But they weren’t, not in class, and not in the short response papers they wrote the following week. The soldier students dominated the discussion that day. At first, they were talking to me, but soon they were talking to each other. They kept going back to the details; they loved what Saunders got right with the details of it all. I wrote “verisimilitude” on the board and thank god everybody ignored me. They liked the part where Saunders described the rich part of town where people lived in “castles,” it reminded them of some of the snobby neighborhoods over by the westside Target where people lived in “Prairie Castles.” They loved the parts where everybody is always saying Thank you for your service to Mikey but always at the most awkward moments. But their favorite was the depiction of what happens to memory and language after trauma, the way it loses context. One student found his favorite passage and read aloud and everybody laughed. That’s so true! they echoed. I couldn’t believe it, the very passage that I’d flagged in my own text to try and avoid—worried about it triggering something I didn’t understand, much less knew how to handle—was the one that seemed easiest for them to talk about. He read:

I asked the first guy if he remembered the baby goat, the pocked wall, the crying toddler, the dark arched doorway, the doves that suddenly exploded out from under that peeling gray eave.

“I wasn’t over by that,” he said. “I was more by the river and the upside-down boat and that little family all in red that kept turning up everywhere you looked?”

I knew exactly where he’d been.

Humiliation and shame are twin themes that run through almost all of Saunders’ work. But humiliation works differently in “Home.” For one, the hero, Mikey, isn’t impotent. Or I should say he isn’t impotent in the way other Saunders other characters often are. He is strong, and through his physical strength he changes things. The problem, though, is that his strength and his power, and what he has done with it, terrifies everybody. Here he has done a nation’s violence for it, but now, after the fact, the nation is embarrassed to look at him.

After class one of the students who’d spoke most loudly during the hour, we’ll call him Jack, hung around. He waited as I talked to another student about a midterm she’d missed. When she left, and Jack could see that we were alone, he spoke. “Mr. McCormick,” he said (soldier students, no matter what their age, always use the honorific), “I just wanted to say. Like I didn’t want to bring up in class, because . . . I just wanted to say I stayed up all night reading that book. When I got to the end I just cried like a little bitch, you know?” I nodded. And I did.