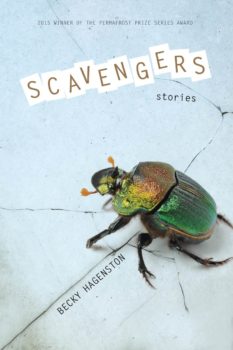

When I read Becky Hagenston’s collection Scavengers (University of Alaska Press, 2016), I was immediately drawn into her story-worlds—the world cracked open by characters craving more to life than meets the eye. In the title story, she invites us in with dung beetles: clues to an underworld, a metaphor for the subconscious. In Egyptian mythology, they roll the sun across the sky, but in “Scavengers,” they illuminate the protagonist’s latent desire for a child.

Before losing her job as an administrative assistant, Margaret’s been on a televised game show where she met a fellow contestant who gives her a cage of scarabs, dung beetles. When, distracted from her work by the allure of Hollywood, she’s fired, she doesn’t mind, since she’s hoping to land an acting gig or have a baby, whichever comes first.

Before losing her job as an administrative assistant, Margaret’s been on a televised game show where she met a fellow contestant who gives her a cage of scarabs, dung beetles. When, distracted from her work by the allure of Hollywood, she’s fired, she doesn’t mind, since she’s hoping to land an acting gig or have a baby, whichever comes first.

In the midst of making audition videos for reality shows, a stranger comes to the door on a daily basis, asking for peculiar items that Margaret just happens to have, mostly hidden away in her attic. Finally the stranger, Delores, gives Margaret a present in return: a pregnancy test. She tells Margaret that all the items she’s been asking for are in fact for the baby, to remember its mother by.

It turns out that Delores is a witch who has cast a spell on Margaret’s mother, a sorority sister who once offended Delores in college. “I curse your baby girl and I will take her first born as my own,” she told Margaret’s mother. But the curse turns into just the impetus Margaret needs to find the life’s work she’s really been seeking. She flees to the wilderness where neither Delores nor her mother nor her husband, Donny, can find her and her baby. She also frees the dung beetles to roll the sun across the world, “while the humans filled their arms with all they could hold.”

I read the collection with my mother, from whom I inherited the love-of-reading gene. She mainly enjoys family dramas, like Twentieth Century Women in book form. She reads at night, in bed, after long days of nursing. She says her novels remove her from her world of woe; they’re a release, a catharsis, that outpouring of feeling, the rush of empathy made all the sweeter because she isn’t responsible for fixing the woe.

She didn’t get “Scavengers.” She, like Margaret’s mother, wanted resolution. Why would the author do this to us, leave us not only with a dangling curse, but also a destroyed marriage! I, on the other hand, loved it. What I saw that the author does to us is give us just what she promised: more than meets the eye. Where some readers, like my mother, might dismiss the story after the witch’s (or even the dung beetles’) introduction, in these strange elements I see how strong is our main character’s desire to get out from under conventional life. The witch brings to life a palpable sense of life’s curse, whether there actually is one or not. Mom and husband try to beckon Margaret back to her senses: You have a home, you had a job, you’re about to have a kid, you’ve arrived at the dream! What more could you want?

The dung beetles point to what she wants. She wants life enlarged enough to include myth, to include the miraculous love of a child as well as the disastrous curse of work-a-day sameness that drives us to look beyond. Perhaps, I think Hagenston suggests, there is more to want. Reality can make that hard to see. Stories like this one give us a glimpse of what else is out there. They ask something of us, too, that we keep desiring, listening to what wells up from within us.