I use “Tiny, Smiling Daddy,” from Mary Gaitskill’s collection Because They Wanted To, to help fiction students understand the value of stories that lack epiphanies, or any clear transformation in their characters. In Gaitskill’s story, a father who has long struggled with his only child’s sexuality finds that his daughter has published an essay about their difficult relationship, one in which she articulates the limitations of her father’s love. The father, aptly named Stew, is insulted, embarrassed, and rocketed back to moments in the past, gaps in understanding that have left him feeling assaulted and alone. In large part, his sense of victimhood is unwarranted—he is the often the one behaving badly here—but he’s prone to petulance and to feeling deeply wronged.

I use “Tiny, Smiling Daddy,” from Mary Gaitskill’s collection Because They Wanted To, to help fiction students understand the value of stories that lack epiphanies, or any clear transformation in their characters. In Gaitskill’s story, a father who has long struggled with his only child’s sexuality finds that his daughter has published an essay about their difficult relationship, one in which she articulates the limitations of her father’s love. The father, aptly named Stew, is insulted, embarrassed, and rocketed back to moments in the past, gaps in understanding that have left him feeling assaulted and alone. In large part, his sense of victimhood is unwarranted—he is the often the one behaving badly here—but he’s prone to petulance and to feeling deeply wronged.

The great achievement of this story, to my mind, is that it cultivates sympathy for an emotional villain—a homophobe who’s pushed his daughter out of the family while simultaneously viewing her in a disturbingly sexual light. Stew’s confused and tender memories of his own childhood, his clear bewilderment in his present life, and his sense of being burdened and left behind by everyone around him ultimately wreak a change in us, a sympathy that can be surprising, delightful, and disorienting at once.

That’s the transformation here—an evolution in our awareness of his vulnerability that changes our sense of who he is and why. This is an ostensible bad guy who turns out, after all, to be desperately lost and unable to change; he greets his daughter’s essay—and his own role in her life—with defensive self-righteousness, but also with deep confusion. In our minds, repugnance slowly gives way to a measured sympathy, and when, as the story ends, Stew is left profoundly alone, we’re there in the living room with him, sharing his uneasy and perhaps unconscious sense of the way his anxiety and alienation will march relentlessly on.

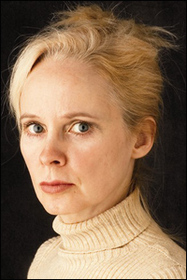

- Read an interview with Mary Gaitskill right here on FWR

- Or, you can Listen to Mary Gaitskill read from the beginning of the story