A writer can never have too much (or too little) advice on how to handle rejection. Every rejection, no matter how discrete, invokes the sensation of being punched in the face, and it’s extremely difficult to be magnanimous while that’s going on. So here’s my advice: with a slight shift in perspective, it’s possible to find rejection thrilling. The first step is learning how to take a punch. (Having been raised in a boxing family, I acquired this knowledge early in life.) The second step is learning how to enjoy taking a punch. That’s the hard part.

A writer can never have too much (or too little) advice on how to handle rejection. Every rejection, no matter how discrete, invokes the sensation of being punched in the face, and it’s extremely difficult to be magnanimous while that’s going on. So here’s my advice: with a slight shift in perspective, it’s possible to find rejection thrilling. The first step is learning how to take a punch. (Having been raised in a boxing family, I acquired this knowledge early in life.) The second step is learning how to enjoy taking a punch. That’s the hard part.

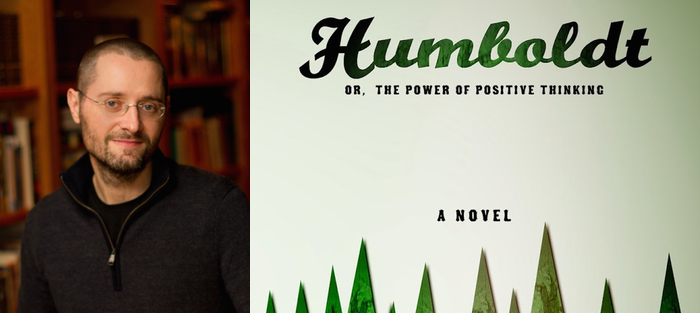

Once my debut novel Humboldt: Or, The Power of Positive Thinking (Chicago Center for Literature and Photography (CCLaP), 2014) was complete, I suffered twelve straight months of near-constant rejection. This did not come as a surprise. In fact, this rejection was so unsurprising that I had already parodied it in the novel itself. In a scene that occurs during intermission of Das Rheingold at Lincoln Center, after an initial burst of interest, Humboldt’s lifestory is rejected for publication in a curt exchange that includes numerous looks of “literaryagentagony.”

But during those twelve months, how much was I really suffering? Is it possible to say that those months were also thrilling? After years of Billy Budd-ing everything I wrote, it finally felt like I had risen from the depths of hobbywriting to the not-so-lofty lows of stock rejection letters. To rephrase this feeling without the portmantypo: I finally felt like a real writer, “right down to that little writer’s frown on my face” (Billy Collins).

I realize that this may sound unbelievable, but the publisher that finally accepted my novel was the absolute last publisher I queried. My submission to CCLaP was something of an afterthought; my original plan was to query a different small press that had been profiled in Poets & Writers. As I was jotting down this other press’ mailing address, I happened across CCLaP’s. Once my first query had been sent, I decided that I might as well send out one more before declaring, “Ahoy, Handsome Sailor.”

Having experienced so much rejection, my sudden acceptance was as unsettling as it was unexpected. If rejection is thrilling, how can I describe the sensation associated with success? I’ve been struggling with this question ever since the first shipment of my books appeared on my doorstep. Yes, opening that box was thrilling; and yes, holding that first copy in my hand was exhilarating, but there was something more, something that can’t easily be described by mere adjectives.

Having experienced so much rejection, my sudden acceptance was as unsettling as it was unexpected. If rejection is thrilling, how can I describe the sensation associated with success? I’ve been struggling with this question ever since the first shipment of my books appeared on my doorstep. Yes, opening that box was thrilling; and yes, holding that first copy in my hand was exhilarating, but there was something more, something that can’t easily be described by mere adjectives.

The single best word that summarizes the sensation is intoxication. That entire afternoon acted as a reminder of how Hans Jonas once described the ancient Gnostics as experiencing the “intoxication of unprecedentedness.”

Becoming a novelist means becoming intimate with intoxication. Novels should be intoxicating. The more the words glitter and beguile, the more a reader focuses on their pages. Television offers no such perspectival pleasures, neither do movies. Nonfiction can inform and enlighten, but seldom does it touch upon what Michel Foucault, in The History of Madness, calls “the sensible drunkenness” of the world. Madness is a notoriously slippery subject for any author; within his très grand tome, Foucault employs a wealth of creative phrasing to encapsulate the moment when reason fails, logic falters, and humans are left flailing within an abyss of confusion as the world roars forward as if nothing is amiss. (With each new phrase – my other personal favorites include “animal unreason” and “dazzlement” – I envision translator Jonathan Murphy shaking his head in disbelief and muttering under his breath: “Encore, Michel! Sacrebleu!”)

Humboldt: Or, The Power of Positive Thinking is filled with Foucault’s “sensible drunkenness.” Within the narrative, I coin hundreds of portmantypos, numerous characters are casually slaughtered, only to be resurrected via creative secondbirths, and one section is written entirely in a language that I don’t speak (en français). Whenever anyone corners me and questions how any of this makes sense, my only recourse is to recount Beckett’s cumbersome joke from Endgame about the irate Englishman and the timid, yet excessively attentive tailor.

‘Come back in four days’ is what the Englishman is originally told, but every time he returns to the tailor’s shop, he is turned away by a different excuse. Eleven days later, the tailor claims to have made “a hash of the crotch.” Thirty-five days later, he “ballockses the buttonholes.” Finally, after the fifth failed attempt to pick up his trousers, the Englishman loses his patience.

“In six days, do you hear me,” the Englishman shouts, “six days, God made the world. Yes Sir, no less Sir, the WORLD! And you are not bloody well capable of making me a pair of trousers in three months!”

“But, sir,” the tailor calmly responds, “look at the world… and look at my TROUSERS!”

Take a moment and look at the world: is it not over-brimming with “sensible drunkenness?” Does love not dry up quicker than sperm? (Charles Bukowski) With staggering swiftness, does the warmth of human kindness not cool into hatred’s nuclear winter? Do your most cherished certainties not turn into chimeras as you grossly gape on? And at the slightest insult, does your sky not darken, your heart not harden, and your moral compass, which you once held so dear, not erode into such irrelevancy that it might as well be a paraplegic’s pedometer? Where is the sense in any of this? And in the face of such acts of sheer senselessness, what better balm is there than the intoxication of fiction?

This essay began as advice for how to handle rejection, but I fear that it has turned into something very different, something stranger. It has turned into a plea for unprecedentedness. As a novelist, intoxication is your duty. Drink up as much of it while you can, for you never know when your cup will be empty. And as you drink, remember this: yes, it’s easy to be overworked and overwhelmed; yes, it’s easy to feel confused and abused, but when you’re experiencing the “intoxication of unprecedentedness” you can survive anything, even a rejectionpunch in the face. And when you do, you’ll realize that pain, like failure, is fleeting. Once it passes, what remains is a rockhard resolve. And such resolve is the bedrock that success is built upon.