Three years into the doctoral program at Florida State University, my wife and I had tired of living like graduate students—the hard studying, hard partying, and hard poverty of it all. I thought I’d found a way out when I was offered a job and a place to live at a boarding school in western North Carolina. I called my dissertation director, Robert Olen Butler, to share my plans.

“Is it money?” Bob asked. “Do you need money?”

“You think it’s a bad idea? I’ll have time to write in the afternoons.”

“If you fart on the squash court,” he said, “they’ll make you the head coach.”

I turned down the job. A few days later, Bob called and said if I still needed extra cash he’d hire me as his assistant. I spent the next two years driving thirty miles west of Tallahassee twice a week to work at his plantation house (the Asa May House) in Capps, Florida (Population 1).

He’d never had an assistant so at first he wasn’t sure what to do with me. I offered that I was good at yard work. He thought about that but decided manual labor violated the university’s terms of an assistantship. So, he put me to work preparing his income tax return. I fretted over that for a good month—doing things I was mathematically unqualified for like calculating the exchange rate for travel receipts to places like Vietnam, Singapore, and China—and I was terrified he’d end up arrested for tax fraud.

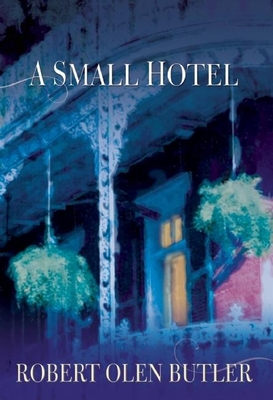

After that, I spent the next few months running errands to free his days for writing. I ordered and assembled mosquito traps to place outside his writing cottage. I organized his vintage shoe collection. I took his Bichons Frises—Sophie, Sadie, and Susie—to the groomers. I worried his old pickup to Tallahassee to repair the brakes and steering. I carried trash to the county dump… At the end of each workday, though, he’d invite me into the cottage and read aloud what he’d written that day and ask for my thoughts. I was his first reader for Hell and a screenplay that he expanded into his newest novel, A Small Hotel.

After that, I spent the next few months running errands to free his days for writing. I ordered and assembled mosquito traps to place outside his writing cottage. I organized his vintage shoe collection. I took his Bichons Frises—Sophie, Sadie, and Susie—to the groomers. I worried his old pickup to Tallahassee to repair the brakes and steering. I carried trash to the county dump… At the end of each workday, though, he’d invite me into the cottage and read aloud what he’d written that day and ask for my thoughts. I was his first reader for Hell and a screenplay that he expanded into his newest novel, A Small Hotel.

I learned a great deal about writing watching him work through those novels, but that wasn’t the best part of the job. One afternoon, I found a cardboard box in the cottage’s attic full of notebooks, manuscripts, and letters. I sat down on a joist between rows of pink insulation and rummaged through the papers—here were the four novels he’d written by hand (in pencil on yellow legal pads) while commuting on the Long Island Rail Road; here were letters from people like Anatole Broyard, Staige Blackford, and Harry Crews; and, here was an acceptance letter for “Crickets,” the very first story written for A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain. I dragged the box down the attic stairs to show Bob. He said, “I think I have a dozen more like that inside the house.”

For the next year and a half, I built an archive that will one day become an online resource called “The Butler Collection.” Each box contained all of the notebooks, working notes, handwritten drafts, typescripts, edited manuscripts, and correspondence that went into creating all of his works. The problem was that the boxes were a jumble of papers. A play he’d written in college might be mixed in with a draft of a story from Tabloid Dreams and a screenplay he’d written for Robert Redford. It was my job to parse through and organize these manuscripts. For example, I would open one box and find his research for Countrymen of Bones and then dig through all the other boxes until I was able to recreate his method of composition from first draft to completed novel.

For the next year and a half, I built an archive that will one day become an online resource called “The Butler Collection.” Each box contained all of the notebooks, working notes, handwritten drafts, typescripts, edited manuscripts, and correspondence that went into creating all of his works. The problem was that the boxes were a jumble of papers. A play he’d written in college might be mixed in with a draft of a story from Tabloid Dreams and a screenplay he’d written for Robert Redford. It was my job to parse through and organize these manuscripts. For example, I would open one box and find his research for Countrymen of Bones and then dig through all the other boxes until I was able to recreate his method of composition from first draft to completed novel.

Bob didn’t hold me to any deadlines. He was happy I was occupied. So, I moved slowly and read each draft of a story or novel from a three-word image on an index card to the publisher’s proof. I wanted to absorb his writing process, to understand the decisions he’d made as he revised. I did this for almost every published book he’d written, which at the time was ten novels, five story collections, and one book of nonfiction. Perhaps most helpful for an aspiring writer, like me, was that I did the same thing for the twelve full-length plays, forty-four short stories, and five novels that he never published.

Building the archive was an incredible experience, invaluable really, and I’m lucky to have had it, but I hesitate to say it was my favorite part of the job. That came early during my assistantship (when we agreed to ignore the university’s guidelines) and he had me cleaning out closets and attics. I’d fill his pickup with junk and then we’d drive down the long dirt road to the county dump. We’d talk writing some, sure, but mostly we’d just talk. Bob would back the truck to the dump’s edge and dig through the bed for breakables and heavy things like old window units and typewriters. Then, we’d stand on the tailgate together and hurl them with all of our might into the pit, laughing and congratulating each other like old friends whenever something smashed in a spectacular way.