A few years after I graduated high school, a friend gifted me a well-worn trade-paperback edition of John Updike’s Pigeon Feathers and Other Stories (Knopf, 1962). The timing was perfect; for complex reasons I later came to regret, I had not gone off to college after high school but was instead attempting to deliberately set my own course for a reading and writing life. I was hungrily pursuing fiction I hadn’t found in the yellowed anthologies we read in high school—anthologies, I imagined, that were so old they may have been the same ones my father read when he had attended the same school decades earlier.

I was drawn into Updike’s early story collection by not only the precision of his language and curious tug of his lines—such as the titular story’s opening: “When they moved to Firetown, things were upset, displaced, rearranged.”—but also for his obvious affection for small towns. As I read Updike and struggled to build my first short stories from the fodder of my own small-town upbringing, I drew a sort of inspiration from just knowing Updike made his home in Massachusetts, an hour down the coast from my seaside village in southern Maine. It excited me to know that the tweedy man of American letters was nearby as he churned out all those novels, stories, poems, essays, and reviews with seemingly indefatigable energy. Updike the writer, perhaps even more than his writing, settled firmly into my imagination.

I was drawn into Updike’s early story collection by not only the precision of his language and curious tug of his lines—such as the titular story’s opening: “When they moved to Firetown, things were upset, displaced, rearranged.”—but also for his obvious affection for small towns. As I read Updike and struggled to build my first short stories from the fodder of my own small-town upbringing, I drew a sort of inspiration from just knowing Updike made his home in Massachusetts, an hour down the coast from my seaside village in southern Maine. It excited me to know that the tweedy man of American letters was nearby as he churned out all those novels, stories, poems, essays, and reviews with seemingly indefatigable energy. Updike the writer, perhaps even more than his writing, settled firmly into my imagination.

A decade and a half after I first read Updike—and a few years after his 2009 death—I spent a Sunday morning wandering the austere galleries of the Peabody Essex Museum just north of Boston. After lunch I decided to make my way home to Maine on coastal Route 1A. It was a Sunday afternoon. I didn’t have anywhere to be. The chance to wend my way through curious, quiet small towns rather than thrumming along the characterless highway north was too good to pass up.

When I rolled into Ipswich, Massachusetts, and over the narrow, gently arched Choate Bridge, I slowed to admire the handsome Caldwell Building beside the river. Updike kept an office in the Caldwell in the 1960s after he’d departed his position as a staff writer at the New Yorker. I pulled the car to the curb and scanned the windows of the building’s upper floors. I wondered which office Updike might have sat gazing out while writing Rabbit, Run (Knopf, 1960) or Couples (Knopf, 1968). [1] I know great writing can and does happen anywhere, yet I am always surprised by the strange electric charge I feel when I find myself somewhere it did happen. [2]

Updike used to walk to his office in the Caldwell from his rambling seventeenth-century Colonial a few blocks away. When he broke off writing midday, he walked downstairs for a sandwich at the Dolphin Restaurant. Standing on the sidewalk that day in Ipswich, I looked up and down the road, hoping to spot an A&P grocer. I imagined a young Updike in his office in the middle of summer, windows pushed wide for the breeze off the river—reading glasses slipping down his hawkish nose—typing the opening line of his celebrated story “A&P”: “In walks these three girls in nothing but bathing suits.”

I never met John Updike. I never even heard him read in person. Yet, in a roundabout way, I owe him a great debt of thanks: because of Updike, I met Ann Beattie. And after I’d known Beattie for several years, I ended up on a strange literary guest of sorts related to Updike’s inclusion of her story “Janus” in The Best American Short Stories of the Century (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000).

The tenuous thread I’ve woven from Updike to Beattie to me—and to be honest, it’s something closer to nonexistent even more than it is tenuous, though it brings a smile to my face—is a matter of coincidence, curiosity, and a bit of compulsive research. The whole thing began with another writer altogether: Andre Dubus.

In 2007, I began the long and slow but joyous process of re-reading, researching, and conducting interviews in order to write a long essay on Dubus for Poets & Writers Magazine. Updike was a great admirer of Dubus’s fiction, in particular of his ability to write uniquely alive characters. “[He] is a shrewd student of people who come to accept pain as a fair price for pleasure, and to view right and wrong as a matter of degree,” Updike wrote in his New Yorker review of Dubus’s collection The Times Are Never So Bad (Godine, 1983). He reviewed several of Dubus’s books with enthusiasm and his usual precision of observation. When I described Dubus’s ability to write convincingly from the point of view of women, I pulled a line from Updike’s review of the novella Voices from the Moon (Godine, 1984) in the New Yorker: “Mr. Dubus has taken especial care with his three women,” he wrote, “and has much to tell us about female sexuality and, contrariwise, the female lust for solitude…” [3]

As I reviewed my notes to write a short section in my essay about how Dubus handled female characters in his fiction, giving them the same complexity and agency as his male characters, I realized the other archival quote I’d gathered was from Tobias Wolff’s afterword [4] to the Xavier Review Press anthology Andre Dubus: Tributes (2001). The realization made me laugh: I had two male writers saying how well their fellow male writer could write about women. That simply wouldn’t do. I wanted the opinion of a female short story writer, and not just anyone, but a celebrated contemporary of Dubus. And I knew just who to contact: Ann Beattie. If only I had her address.

As I reviewed my notes to write a short section in my essay about how Dubus handled female characters in his fiction, giving them the same complexity and agency as his male characters, I realized the other archival quote I’d gathered was from Tobias Wolff’s afterword [4] to the Xavier Review Press anthology Andre Dubus: Tributes (2001). The realization made me laugh: I had two male writers saying how well their fellow male writer could write about women. That simply wouldn’t do. I wanted the opinion of a female short story writer, and not just anyone, but a celebrated contemporary of Dubus. And I knew just who to contact: Ann Beattie. If only I had her address.

I knew about the Beattie-Dubus connection because of the dedication in Dubus’s essay collection Broken Vessels (Godine, 1991), a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. In 1986, while driving home from Boston, Dubus stopped to help a couple whose car had collided with a motorcycle that had been abandoned on the highway. In the confusion, an oncoming car traveling nearly sixty miles an hour struck Dubus. He was left with thirty-four broken bones, his left leg was eventually amputated below the knee, his right leg crushed to the point of uselessness. The accident made a wheelchair-bound amputee of the once physically active author. About a year later, a group of Dubus’s literary friends and admirers gathered in Boston for a series of fundraiser readings to offset his medical bills. The group included Beattie, E.L. Doctorow, Gail Goodwin, John Irving, Stephen King, Tim O’Brien, Jayne Anne Phillips, John Updike, Kurt Vonnegut, and Richard Yates. [5] Dubus thanked the group in Broken Vessels.

Like many other aspiring writers who came of age in the early 1990s, I had read Beattie since I’d graduated high school. She was—like Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, Joy William, and Wolff—a contemporary master I read not only for pleasure but for instruction, and to discover what a short story could contain. Back in 2007, I didn’t know Beattie personally, and I had no reason to believe I could convince her to offer quotes for my essay. But eventually I remembered Ann and I did have a mutual friend in a well-known Maine painter. I emailed the painter-friend, DeWitt Hardy, who sent me an email address for Ann’s husband, the painter and sculptor Lincoln Perry; I emailed Lincoln, who sent me Ann’s email. I screwed up my fan-boy admiration and wrote Ann an email asking if she would be interested in contributing a few insights on female characterization in Dubus’s fiction. I sent the note one afternoon and then tried to put it out of mind, assuming she’d never respond. It was not lost on me, however, that I would never have reached out to Ann if I had not realized the inappropriateness of quoting Updike—a writer frequently, and some cases fairly, accused of chauvinism—on writing women.

The very next morning after I’d had sent my email, I found a 1,000-word response from Ann waiting in my inbox. “Dubus lets us watch fairly conventional power struggles between men and women work out unexpectedly,” she wrote, “because there is always the inclusion of fate…everyone is swept up in something larger than any individual.” I remember my heart thudded as I read Ann’s expansive response. Holy shit, I thought, this is more than I could have hoped for. But it was, I would discover, typical of Ann’s generosity.

After my essay “The Art of Reading Andre Dubus: We Don’t Have to Live Great Lives” was published, Ann invited me to lunch at her house for an informal celebration. I arrived with a large canvas tote bag brimming with first-edition Beattie books; I couldn’t help myself. We sat and talked on the author’s screened back porch. She recalled Dubus with great affection and described how he could hold court and command a room, even from his wheelchair. He could be at turns chivalrous and flirtatious. Ann shared stories of reading with Dubus on the book tour for Dancing After Hours (Knopf, 1996), which would be his final book and final book tour. Her memories were like manna. I was riveted.

We stayed on the porch for hours. Ann prepared a big, delicious summer salad, poured some wine, and kept talking. Later, I unpacked the books from my canvas bag onto the table. “Oh, my!” said Ann, and then patiently signed the stack. [6]

Several months after my Dubus article appeared, Updike haunted me once again: I noticed on the Wikipedia page for Dubus there were listed just two external links for further references on the author: one was Updike’s 1985 New Yorker review of Voices from the Moon, the other was to my essay. There we were, side by side in pixels: Mr. Updike and me.

In the early winter of 2015, I began my research to write a profile of Ann to coincide with the publication of her nineteenth book, The State We’re In: Maine Stories. I wasn’t long into my research when Updike appeared again.

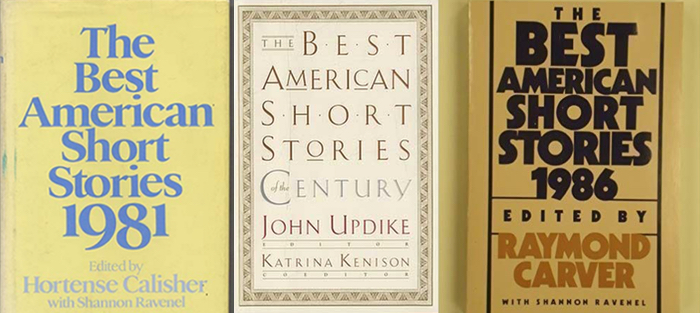

When Updike and Ann first met, the elder statesman of American letters was clear about his admiration for her writing gifts: “You figured out how to write an entirely different kind of story,” he told her; Ann blushed. When Updike took up the unenviable task of selecting stories for The Best American Short Stories of the Century, he included her story “Janus” from the 1986 edition of the series, which had been guest edited by Raymond Carver. Ann was certainly pleased to be included in the centennial anthology, but she had grown weary of “Janus” over the years: “Only because I see how schematic it is,” she says today.

When Updike and Ann first met, the elder statesman of American letters was clear about his admiration for her writing gifts: “You figured out how to write an entirely different kind of story,” he told her; Ann blushed. When Updike took up the unenviable task of selecting stories for The Best American Short Stories of the Century, he included her story “Janus” from the 1986 edition of the series, which had been guest edited by Raymond Carver. Ann was certainly pleased to be included in the centennial anthology, but she had grown weary of “Janus” over the years: “Only because I see how schematic it is,” she says today.

In her 2011 “Art of Fiction” interview with The Paris Review, Ann describes nervously approaching Updike at a publication party for The Best American Short Stories of the Century and asking him why he selected this particular piece: “He said, ‘It was the only one available to me.’ And it was the first time I realized that I had never had another story in an edition of Best American, except for that one. He didn’t like that story any more than I did.”

Indeed, in Updike’s introduction to the anthology he says he selected the story because the Best American series had “shunned her early efforts, leaving us with only the later, not entirely typical but still dispassionate ‘Janus.’”

I was stunned. Ann Beattie had only appeared in the Best American series once between her first publications in the mid-1970s and Updike’s curating of The Best American Short Stories of the Century in 2000? I was flabbergasted. But then, I thought, there was Ann herself confirming the assertion in her Paris Review interview. So I moved on with my research.

When I first suggested a profile of Ann to Kevin Larimer, my editor at Poets & Writers magazine, I told him I wanted to write a far-reaching piece. In addition to gathering fresh quotations on a much-profiled author like Ann, I knew there were inaccuracies in her literary biography that deserved correcting. For example, when it came to writing about Ann’s first submissions to the New Yorker in 1972, rather than depending on conflicting information in old articles, I called 94-year-old New Yorker fiction editor Roger Angell to discuss her stories and his first acceptance of her work in 1974.

As I researched, made notes, and conducted interviews, in the back of my mind I could never accept that Ann went more than two decades with only one story appearing in the Best American series. In a moment of borderline obsession, I couldn’t shake my disbelief: I decided to review the table of contents in every edition of the Best American Short Stories from 1974 to 2000.

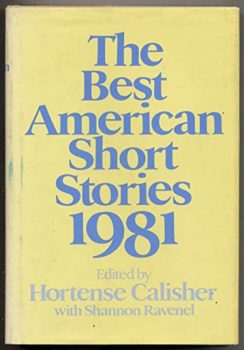

With conflicting feelings of guilt and pride, I discovered that during the monumental task of editing The Best American Short Stories of the Century, Updike had gotten something wrong when he selected Ann’s “Janus” out of what he believed was necessity: he had missed her story “Winter: 1978” from the 1981 edition of the series, guest edited by Hortense Calisher. [7]

It appears Updike compiled the century edition by—for the most part—selecting a single story for each year. Rather that selecting Ann’s “Winter: 1978” from the 1981 edition, he instead chose Cynthia Ozick’s “The Shawl.” This can only mean Updike went through each collection’s table of contents before making his selection and—even more oddly—making the assertion in his introduction that Ann had only appeared once in The Best American Short Stories series. Perhaps even more surprising about his oversight is the fact Updike himself appeared in that same 1981 edition with the pithy vignette-of-a-story “Still of Some Use.” [8]

Ann and I were sitting again on her screened back porch, recording a conversation for the profile I was writing, when I told her about Updike’s mistake. Ann’s eyes went wide and her mouth fell open. She had, after all, believed Updike’s assertion so thoroughly that she’d repeated it as fact in her Paris Review interview.

“No,” she said. “Really?” After a decade and a half of believing Updike, she seemed startled by my claim. “Okay, come on,” she said and led me inside and up the back staircase.

In the narrow hallway at the top of stairs, a floor-to-ceiling bookcase ran the length of one wall. Ann searched for a moment, then found the section with many years of editions of Best American Short Stories.

In the narrow hallway at the top of stairs, a floor-to-ceiling bookcase ran the length of one wall. Ann searched for a moment, then found the section with many years of editions of Best American Short Stories.

“1981,” she said softly, and scanned the shelves. “I just can’t believe it….”

After a moment of searching I spotted the yellow-covered edition with large blue type.

“Here it is,” I said. I pulled down the volume and opened the edition’s table of contents to her: “Winter: 1978.”

“Well, I’ll be,” said Ann, stunned.

“Do you prefer this story to ‘Janus’?” I asked.

“Yes, yes I do prefer this story.”

We stood in the hallway and together skimmed the story’s opening lines.

Maybe, I have begun to wonder lately, my interest in these little literary details and small facts is silly; too obscure, too niche. Maybe none of this stuff matters. Who cares, after all, about the table of contents from decades old anthologies? Does it really matter where someone sat when they wrote a particular piece of writing?

And yet, I cannot help it. I find that I care. I find myself helplessly curious and excited by what others might find too obscure and extraneous. Perhaps when you grow up in a small coastal village and don’t go off to college after high school, but instead attempt to set your own course for a reading life because you aspire to a writing life, there is something about even the littlest literary details that can take on an outsized importance. I see now that I have become who I am because I have remained open to the potential of being rattled by the power of stories. I have discovered stories—short stories, novels, novellas, and everything in between—that have brought my own memories and experiences into sharper understanding for me, and I have discovered stories that unlocked me to new ways of seeing. In my life, imagined stories and lived stories merge.

On that lazy Sunday afternoon driving home from Boston when I stopped to admire the Caldwell Building in Ipswich where young John Updike kept an office and wrote some of his early—and best—work, I knew there was another nearby literary landmark worth tracking down: in 1970, Updike moved a few miles out of downtown to a larger, more secluded house.

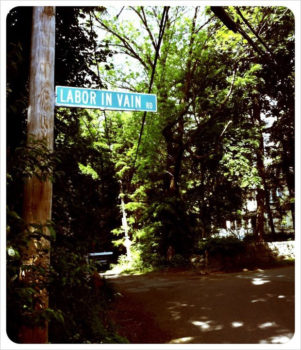

The densely packed Ipswich village of saltboxes, capes, and colonials quickly gives way to woodlands. Near the end of the narrow, rolling Labor-in-Vain Road, I found Updike’s stately old house overlooking a salt marsh and tidal river. Across from the house a short line of cars was parked haphazardly along the broken gravel road’s shoulder. It wasn’t a gathering of literary gawkers or members of the John Updike Society on a guided house-tour. It was locals. Up ahead on the narrow bridge over the river, teens hooted and flew in arching leaps into the cold, brackish water. Tan boys mugged and showed off for girls who glistened in their bikinis. Everyone was wet and sparkled in the sun. Everyone was beautiful.

The densely packed Ipswich village of saltboxes, capes, and colonials quickly gives way to woodlands. Near the end of the narrow, rolling Labor-in-Vain Road, I found Updike’s stately old house overlooking a salt marsh and tidal river. Across from the house a short line of cars was parked haphazardly along the broken gravel road’s shoulder. It wasn’t a gathering of literary gawkers or members of the John Updike Society on a guided house-tour. It was locals. Up ahead on the narrow bridge over the river, teens hooted and flew in arching leaps into the cold, brackish water. Tan boys mugged and showed off for girls who glistened in their bikinis. Everyone was wet and sparkled in the sun. Everyone was beautiful.

I watched the teens leap into the water, pull themselves up the rocky embankment beside the bridge, and then leap again, sometimes from the bridge’s railing. They shrieked and applauded one another. They were careless and happy. I watched and smiled, and imagined Updike standing quietly on the screened-in porch of his old house, watching the teenagers, drawing slowly on a cigarette, the gears of his mind clicking and humming, already filing away the afternoon’s scene as fodder for a future short story.

When I turned my gaze from the bridge-jumpers back to Updike’s old house, a small brown rabbit leapt from the shrubs. It hopped along the lawn, then stopped and sat there, its nose twitching. I stared at the rabbit, which sat motionless, wondering if it too was listening to the kids’ gleeful shrieks and splashes. We stayed like that, staring at one another, for what seemed like a long time before the rabbit hopped away into the tall grass at the lawn’s edge.

FOOTNOTES

-

[1]

While the promiscuous sex in Updike’s Couples seems benign by today’s standards, when I served on the board of trustees at my local library in the mid-2000s, a longtime volunteer told me there had once been a “reading committee” that reviewed all potential purchases for the library’s collection. She told me there had been contentious disagreement among the group about Couples when it was first published. In the end, the library purchased the novel and put it into circulation. -

[2]

While visiting Key West several years ago, I was surprisingly moved while standing in front of the former Ford dealership where Hemingway once rented an apartment and worked on A Farewell to Arms—this was before he bought his famous house on Whitehead Street and settled for a time on the island. When we visit my cousin’s family farmhouse on North Haven Island in Maine it still feels haunted by the fact Elizabeth Bishop rented there for seven summers and wrote her famous eulogy-poem to Robert Lowell there; Bishop’s Oxford English Dictionary purchased at Shakespeare & Co. in Paris is still on the shelf, left behind after her final stay. When visiting my cousin’s in Lewes, England we made the short drive one overcast day to visit Virginia Woolf’s Monk’s House in Rodmell, where I pulled down a soft fig from a tree in the yard. On a road trip down Highway 1 in California, I once stopped in the old hippie town of Bolinas and stood outside the house where Richard Brautigan took his life. -

[3]

Updike’s review, “Ungreat Lives,” paired Dubus’s novella with Thomas Benhard’s Concrete (translated from the German by David McLintock and published by Knopf in 1986). -

[4]

“And he [Dubus] wrote better about women than any man of his generation, both from their point of view and from without. He wrote about mothers and daughters, women in love, women being beaten, women being raped, women being stalked, women working, women being friends with other women, women loving their husbands and committing adultery and saving themselves and their children from bad men. Each of his women is particular and unexpected, her moral and physical nature without a shadow of male fantasy or condescension.” —Tobias Wolff -

[5]

Both Vonnegut and Yates were Dubus’s teachers at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, while Irving was a classmate. -

[6]

After our long lunch in the summer of 2008, Ann and I kept in regular touch. In the spring of 2010, she offered instrumental behind-the-scenes help when I traveled to the University of Virginia to interview the National Book Award-winning novelist John Casey; the interview led me to write “Beyond the Compass,” my profile of Casey for the 2010 November/December edition of Poets & Writers. -

[7]

Who, you ask, is Hortense Calisher? I had the same question. While no longer widely read, Calisher—who passed away in 2009 at the age of 97—was a three-time National Book Award finalist who published her first book in 1951 and went on to publish two dozen works of fiction and memoir. The Calisher-edited 1981 edition of The Best American Short Stories reads like a fascinating transitional year of sorts with several younger emerging writers—such as Bobbie Ann Mason whose debut collection Shiloh and Other Stories wouldn’t be published until 1982—as well as an early generation of established masters, such as Elizabeth Hardwick, who had begun publishing books before Mason was even born. -

[8]

And in another literary coincidence, Andre Dubus’s story “The Winter Father” appears the same edition.