After college, I ran a small, independent bookstore in Madison, Wisconsin, with my brother-in-law, fiction writer Dean Bakopoulos. And every weekend during those four years, I was the one who opened the shop on Saturdays. This meant arriving early, usually around seven in the morning. In winter, it would still be dark. And depending on the season, I’d either shovel the sidewalk and throw down some salt, or I’d sweep off the front steps. Next, I’d bring in the newspapers—one of which I’d save for myself—turn on the lights, and let in the café person who’d just arrived outside. Then I’d unlock the safe, bring out the cash drawers for the registers, turn on the music, and do a quick walk through to make sure that the closers hadn’t left anything lying around at the end of the night before. Once the coffee was brewed, I’d wander over to the café to get myself a cup, as well as a pastry. Usually a marzipan croissant. Or an apple one. Sometimes both. And I’d always add whipped cream. A lot of it. Back then I still had a decent metabolism.

After college, I ran a small, independent bookstore in Madison, Wisconsin, with my brother-in-law, fiction writer Dean Bakopoulos. And every weekend during those four years, I was the one who opened the shop on Saturdays. This meant arriving early, usually around seven in the morning. In winter, it would still be dark. And depending on the season, I’d either shovel the sidewalk and throw down some salt, or I’d sweep off the front steps. Next, I’d bring in the newspapers—one of which I’d save for myself—turn on the lights, and let in the café person who’d just arrived outside. Then I’d unlock the safe, bring out the cash drawers for the registers, turn on the music, and do a quick walk through to make sure that the closers hadn’t left anything lying around at the end of the night before. Once the coffee was brewed, I’d wander over to the café to get myself a cup, as well as a pastry. Usually a marzipan croissant. Or an apple one. Sometimes both. And I’d always add whipped cream. A lot of it. Back then I still had a decent metabolism.

I loved this morning ritual, which is why I never complained about getting up at 6 a.m. on a Saturday to trudge to work. I liked it for many reasons, not just the pastries. For one, New York publishing was closed, which meant I didn’t having anyone from accounts payable telling me that I owed them tens of thousands of dollars and that a collection agency—always, always from Texas—would soon be contacting our business. So that was good. But more importantly (and more seriously) I loved the interaction with our regular customers.

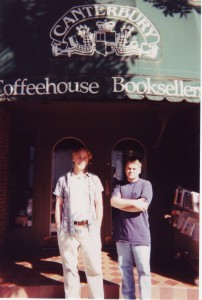

Jeremiah and Dean, 1998: photo credit James Wilson

Paul, who read the Financial Times and who was originally from London, would typically be the first to arrive, often before I had even unlocked the door. He urged me to read Penelope Fitzgerald, and eventually gave me a copy of The Bookshop to be sure I did. Then came the psychology professor and his wife, both of whom loved to hit the Saturday Farmer’s Market early so they’d have their pick of produce. He raved about Oliver Sacks, she about Rohinton Mistry. One by one, the familiar faces came through the door. I don’t remember everyone’s name, but to this day I can still tell you what they read.

Now, before I paint too bucolic a picture of bookselling, let me say that managing an independent bookstore was one of the hardest jobs of my life. In addition to the aforementioned accounting departments of publishers, and the constant threat of going out of business, there was an endless amount of work trying to bring in books that readers would love, finding ways to connect those books with the right audience, arranging author visits, haggling with advertisers, sitting on downtown development committees, and then the general headaches of staffing a store with human beings—some of whom were not inclined to work, others who were inclined to sleep in, and the occasional few who were inclined toward theft.

photo credit: Julio Garciah

But much of the time—particularly those Saturday mornings with their dependable rituals—I was able to talk with fellow readers who were enthusiastic about books. How we read them, why we read them, where we read them—you name it. And whether mysteries or metaphysics, non-fiction or nature writing, Chaucer or children’s literature, there was a world of writing to discuss, much of which I had never heard of. I loved nothing more than learning and contributing to that community.

It is this same sense of community that we try to foster at Fiction Writers Review. One that is made up of tastes and interests as divergent and varied as our contributors. But if there’s one unifying element, I have to say it’s that very same enthusiasm for books. An unabashed, unapologetic, earnest love of “shop talk.”

Talking shop is how I think of everything that we do at our site. For example, we aren’t interested in reviews that are purely evaluative. The “thumbs up” or “thumbs down” assessment of a book doesn’t interest me, or our fellow editors. Nor do we find much use for plot summary. After all, we’re not trying to help you figure out whether you want to read something based on its worth or subject matter. Instead, we push our writers to think of everything in terms of craft. Not “did I like it,” but what was the author doing stylistically that’s interesting to think about?

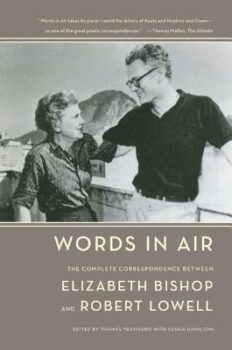

original illustration from

A good review should leave a reader with a new way of seeing the craft of writing, regardless of whether he or she ever picks up the book in question. Similarly, we publish in-depth interviews, most of which run 4,000-6,000 words. This allows enough time for a genuine dialogue to develop between interviewer and author, for the conversation to move beyond talking points. Most importantly, it becomes an actual exchange between two individuals who share a love of a thing. Likewise, our essays are guided by the interests and point of view of our contributors. We’ve published essays ranging from a re-reading of Chekhov’s famous “Lady with the Pet Dog” to a memoir of recovering from total hip replacement surgery while reading Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, to an exploration about why the next Great American Novel might just be a video game.

At the same time, however, Fiction Writers Review isn’t a wiki. This isn’t a posting board. While democratic in terms of content and contributors, there is rigorous editorial oversight, both in terms of what gets published (we often receive several submissions a day) and the multiple rounds of editing that occur with every piece, some of which have taken more than seventeen drafts over the course of five months to reach successful completion.

Now, none of this is unique to an online literary journal. The best print journals have rigorous acceptance and editing standards, they publish a range of essay topics, they feature sustained interviews, and they focus their reviews on thoughtful analysis. But what we also have is what the bookstore provided me: sustained, regular interaction. Almost every day we post new content on our blog—whether industry news, calls for submissions, news items, or general whimsy—and every three to five days we publish a new feature. So each day a reader visits the site, it feels as if there’s an ongoing conversation taking place. This is further underscored by the fact that readers can leave comments and questions and links to related material in response to the work itself. And if a particular author’s work interests them, at the end of each feature we also have a wealth of other resources they can explore—video clips of readings, podcasts, links to further interviews, reviews, and original work by the subject, as well as suggestions for other writers undertaking similar projects.

It is this ongoing dialogue that lends this particular venture its deeper sense of community, for me. Though I subscribe to Zoetrope and Tin House and the New Yorker and Poets & Writers, and an embarrassing number of magazines with glossy covers whose names I won’t speak here, to say nothing of quarterlies ranging from AQR to MQR to VQR—all of which I read and love—I don’t converse with them daily. Fiction Writers Review, on the other hand, is my water cooler. And there is something about the immediacy and closeness that is valuable.

The clearest example I have of this is when Barry Hannah passed away in early March. The news of his death was leaked via Twitter, and was quickly picked up by online journals like HTML Giant, The Rumpus, and The Millions. Long before the New York Times or any other periodical was running the story, a real-time outpouring of sympathy, as well as a wealth of tributes to his work and teaching, was unfolding from his friends, former students, and admirers. I was one of those individuals. Barry was my teacher at the Sewanee Writers Conference several years ago, and I spent the day after his death re-reading his work, meditating how it had shaped me, and writing a short essay about his influence. Because we are an online journal, we were able to publish it on our blog that very day, and within hours it was picked up and re-published (or linked to) in dozens of places across the country. [Here’s the essay in its later, expanded form.] This is another unique aspect of online literary journals and they way they foster community: the work is shareable. Immediately. So there is not just a community of readers of our journal, but also a community that exists among online journals.

The clearest example I have of this is when Barry Hannah passed away in early March. The news of his death was leaked via Twitter, and was quickly picked up by online journals like HTML Giant, The Rumpus, and The Millions. Long before the New York Times or any other periodical was running the story, a real-time outpouring of sympathy, as well as a wealth of tributes to his work and teaching, was unfolding from his friends, former students, and admirers. I was one of those individuals. Barry was my teacher at the Sewanee Writers Conference several years ago, and I spent the day after his death re-reading his work, meditating how it had shaped me, and writing a short essay about his influence. Because we are an online journal, we were able to publish it on our blog that very day, and within hours it was picked up and re-published (or linked to) in dozens of places across the country. [Here’s the essay in its later, expanded form.] This is another unique aspect of online literary journals and they way they foster community: the work is shareable. Immediately. So there is not just a community of readers of our journal, but also a community that exists among online journals.

But perhaps most importantly, I believe that online journals like Fiction Writers Review provide a unique place for emerging writers to join the conversation. After all, few print journals accept book reviews from individuals who haven’t yet published a book themselves. And even if they do, they rarely take unsolicited work. So how does an emerging writer enter this critical dialogue? Here they can. Likewise, the interview is a form that doesn’t have a prominent place in most journals. The average quarterly only publishes one an issue, meaning four a year. Here, we often have more than one a week. And while most publications seek creative nonfiction that is predominately literary journalism or personal narrative, here we are looking for meditations on craft and the writing life.

Again, all of this is “shop talk.” All of this is about bringing together people who believe that talking about writing matters. This is what I found so enriching and gratifying about my bookstore experience all those years ago—what I looked forward to every Saturday even more than those marzipan croissants. Because the best conversations are not only ones that include us, but also ones that are ongoing and endlessly evolving.

Editor’s Note

FWR at AWP: Dean, Mike, Valerie, Jeremiah, Anne, Zachary, Margaret, and Natalie

This essay was originally delivered as a talk at this year’s AWP Writers’ Conference (in Denver) as part of the panel Evolution of the New Media: Online Literary Journals in 2010. Joining our Associate Editor, Jeremiah Chamberlin, were Dan Albergotti (Waccamaw), Dan Wickett (The Emerging Writers Network and The Collagist), and Terry Kennedy (storySouth). The panelists’ presentations ranged from the evolving aesthetics of online journal design to the ways in which lit sites and blogs foster an extended literary community for writers. More than 100 participants attended the panel, which sparked a lively debate (one that continued afterward) on such issues as the sustainability and funding of online projects, the commitment to editorial excellence in a digital landscape, and the future of publishing in this medium. FWR was honored to share this event with such respected journals/editors, and also to have so many readers and contributors in attendance. But for those who weren’t able to make it this year, we wanted to share Jeremiah’s talk with the rest of you at the literary “water cooler.” — Anne Stameshkin

Extras

– Visit and read our fellow panelists’ lit sites and journals: The Emerging Writers Network, The Collagist, storySouth, and Waccamaw.

– The following video, an introduction to each of the online lit journals and communities featured at The Evolution of the New Media session, was designed for and screened at the panel: