The Greek astronomer Ptolemy did what he could. Saddled with a mistaken assumption – that the earth was at the center of the Solar System – he was hard-pressed to make sense of what he saw the planets actually doing.

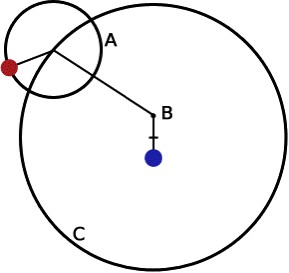

But poor Ptolemy! According to contemporary understanding, each planet was moved around the earth by two spheres. One of these spheres (called the deferent) was centered on the earth. The other (called the epicycle) was actually embedded in the deferent. While the deferent rotated around the earth, the epicycle rotated within the deferent. For various complicated reasons not worth going into, Ptolemy found it helped to also propose the existence of something called the equant, further complicating the already delicate arrangement of interlinked perfect circles:

(Circle A is the epicycle, point B is the equant, and circle C is the deferent. The disk in the center represents the Earth; the other disk represents the planet under observation. There will not be a quiz.)

The problem was, of course, Ptolemy was trying to describe a system that didn’t exist. His point of view, literally, was wrong. He wasn’t looking at the planets from a fixed center, but from a body that was itself circling the sun. Copernicus‘ eventual understanding of this fact led swiftly to the discovery of several other beautiful truths, including those of Kepler, Brahe, and Newton – suggesting that where you stand has everything to do with what you can see. And that if you’re standing in the wrong place, or facing the wrong direction, you’re going to see a very strange, distorted view.

All of which is to say, point of view matters. It might be proposed that an author does well to be relatively Copernican, even if his characters start out almost entirely Ptolemaic. Gabriel in James Joyce‘s “The Dead” begins as a Ptolemaic character (operating on mistaken assumptions) and ends as more or less where the author himself is, in a state of Copernican understanding (getting the big picture). Gabriel starts out believing his biggest worry is the speech he’s got to give. And as to his wife – well, he feels he can afford to joke about her:

“O, Mr. Conroy,” said Lily to Gabriel when she opened the door for him, “Miss Kate and Miss Julia thought you were never coming. Good-night, Mrs. Conroy.”

“I’ll engage they did,” said Gabriel, “but they forget that my wife here takes three mortal hours to dress herself.”

But by the end,

Gabriel felt humiliated by the failure of his irony and by the evocation of this figure from the dead, a boy in the gasworks. While he had been full of memories of their secret life together, full of tenderness and joy and desire, she had been comparing him in her mind with another. A shameful consciousness of his own person assailed him. He saw himself as a ludicrous figure…

The story is unspeakably elegant and heartbreaking, if its conclusion is conceptually rather simple. Gabriel gets it. Now he knows. Knowing doesn’t really help him, but at least he’s not ignorant any longer. His viewpoint has been corrected, and he’s looking at the data with the proper hypothesis, and things make sense. He is now a fuller, more coherent human being. Aaaahhhh, we think, all is set aright.

But it is a business of a higher order to ask that a character remain in at least partial ignorance, or to have a complicated relationship with his or her own ignorance. The dangers of this approach are obvious: the Copernican author treats his relatively Ptolemaic characters with condescension – they can’t know what I know – and renders them less than fully human. But the rewards are significant, and you avoid the encroaching feeling of pat simplicity that threatens to disrupt even so beautiful and nearly perfect a story as “The Dead”.

The supreme example of a character remaining Ptolemaic within a Copernican story is Chekhov‘s “Lady with the Pet Dog”.1 In this story, Chekhov knows nearly everything, and Anna knows, perhaps, only a little less – while the point of view character Gurov knows almost nothing of what goes on around him.

But he sure thinks he does!

A new person, it was said, had appeared on the esplanade: a lady with a pet dog….And afterwards he met2 her in the public garden and in the square several times a day. She walked alone, always wearing the same beret and always with the white dog; no one knew who she was and everyone called her simply “the lady with the pet dog.”

a map of Yalta

Notice how there is, from the story’s very first moment, only generalized and putative knowledge of Anna: “it was said” and “everyone called her”, Chekhov writes, diffusing Anna into the air of Yalta as though puffing her through an atomizer. But Gurov thinks he knows what’s what. He’s a ladies’ man, after all, and reports, of himself, that:

In his appearance, in his character, in his whole make-up there was something attractive and elusive that disposed women in his favor and allured them. He knew that, and some force seemed to draw him to them, too.

Oft-repeated and really bitter experience had taught him long ago that with decent people – particularly Moscow people – who are irresolute and slow to move, every affair which at first seems a light and charming adventure inevitably grows into a whole problem of extreme complexity, and in the end a painful situation is created. But at every new meeting with an interesting woman this lesson of experience seemed to slip from his memory, and he was eager for life, and everything seemed so simple and diverting.

Oh, what love-weariness! What sad, worldly understanding! How sure he is of everything! “He knew that”, “really bitter experience had taught him”, “inevitably grows” — and yet he is still game, he thinks – this is Gurov thinking – and young enough at heart to fall, if only temporarily, in love.

What Gurov doesn’t know is how thoroughly he’s already being played. And Chekhov isn’t going to let him know, either. Not once. Watch what happens next:

What Gurov doesn’t know is how thoroughly he’s already being played. And Chekhov isn’t going to let him know, either. Not once. Watch what happens next:

One evening while he was dining in the public garden the lady in the beret walked up without haste to take the next table.

In other words, Anna makes the first move. She’s chosen him. But he doesn’t notice this; instead, he’s blinkered by what he thinks he knows:

Her expression, her gait, her dress, and the way she did her hair told him that she belonged to the upper class, that she was married, that she was in Yalta for the first time and alone, and that she was bored there. The stories told of the immorality in Yalta are to a great extent untrue; he despised them, and knew that such stories were made up for the most part by persons who would have been glad to sin themselves if they had had the chance…

Note the emphasis on knowledge here, on Gurov’s supposed understanding of the situation, and how, next, Gurov succumbs, perhaps without exactly recognizing it, to the allure of the false stories:

…but when the lady sat down at the next table three paces from him, he recalled these stories of easy conquests, of trips to the mountains, and the tempting thought of a swift, fleeting liaison, a romance with an unknown woman of whose very name he was ignorant suddenly took hold of him.

So Gurov is the kind of guy who will grasp at a convenient fiction if it serves him. But he won’t be bright enough to see that he himself will be taking part in what may well be a fiction of Anna’s making.3

Poor Gurov.

During their first conversation, Gurov learns that Anna is married, though unremarkably (“She was not certain whether her husband was a member of a Government Board or served on a Zemstvo Council”) and that she has, perhaps, come down in the world as a result of her marriage (“she had grown up in Petersburg, but had lived in S— since her marriage two years previously”) and now lives far from the center of things. Gurov, falling under her spell, immediately shows his cards, telling her that “he was a native of Moscow, that he had studied languages and literature at the university, but had a post in a bank; that at one time he had trained to become an opera singer but had given it up, that he owned two houses in Moscow”. In other words, he’s a catch. Anna knows, now, that she has the right fish on the line.

Anton Chekhov

But is she just looking for an affair or for something more substantial? We know she’s spent a long time picking out her target, anyway, so we may deduce that she has grander ambitions – difficult as this will be, given the expectations of the day.

Either way, Gurov remains – apparently – unaware. After their first conversation, considering Anna’s youth and innocence,

…he thought how much timidity and angularity there was still in her laugh and her manner of talking with a stranger. It must have been the first time in her life that she was alone in a setting in which she was followed, looked at, and spoken to for one secret purpose alone, which she could hardly fail to guess. He thought of her slim, delicate throat, her lovely gray eyes.

“There’s something pathetic about her, though,” he thought, and dropped off.

Poor Gurov!

A week passes, and the acquaintance deepens. They go together to the pier to watch the steamer come in with the new arrivals. When you’re expecting someone to come, you bring flowers – and Anna has brought flowers. Who is she expecting? It’s never mentioned, but might it be her husband? Well, maybe:

Owing to the choppy sea, the steamer arrived late, after sunset, and it was a long time tacking about before it put in at the pier. Anna Sergeyevna peered at the steamer and the passengers through her lorgnette as though looking for acquaintances, and whenever she turned to Gurov her eyes were shining. She talked a good deal and asked questions jerkily, forgetting the next moment what she had asked; then she lost her lorgnette in the crush.

The festive crowd began to disperse; it was now too dark to see people’s faces; there was no wind any more, but Gurov and Anna Sergeyevna still stood as though waiting to see someone else come off the steamer. Anna Sergeyevna was silent now, and sniffed her flowers without looking at Gurov.

So, yes, it might be her husband she’s waiting for (she has no use for him, but it’d be nice to be paid some attention to). It might be a lover or a friend.

Or it might be nobody at all. After all, why would she bring Gurov down to the pier if her husband’s coming, or a lover, or even a friend? Chekhov never tips his hand here. Gurov does seem astoundingly, even willfully thick; either he’s actually this slow or he’s intentionally somehow decided on this unacknowledged unknowing because for some reason it pleases him to let things remain unsaid with Anna; maybe he thinks it’s sophisticated to not notice, even to himself, that the object of his attention has just been stood up by – well, by someone. But given Gurov’s inattention to this point, we may be justified in deciding that he’s just a bit of a stiff, and that he hasn’t yet figured Anna’s angle – or that he hasn’t yet seen that she has one at all.

At any rate the ruse, or the apparent ruse (either seen or unseen!) works, because here’s what happens next:

“The weather has improved this evening,” he said. “Where shall we go now? Shall we drive somewhere?”

She did not reply.

No indeed! Silence as the trap is sprung!

Then he looked at her intently, and suddenly embraced her and kissed her on the lips, and the moist fragrance of her flowers enveloped him; and at once he looked round him anxiously, wondering if anyone had seen them.

“Let us go to your place,” he said softly. And then walked off together rapidly.

The air in her room was close and there was the smell of the perfume she had bought at the Japanese shop. Looking at her, Gurov thought: “What encounters life offers!”

So Anna has seduced Gurov, very possibly without him having noticed the elaborate nature of her designs on him; and from Anna’s point of view this is good. But now what? What does Anna want? Does she just want an affair, or does she want more?

If we suspect she wants to extend the affair, and to capture Gurov in a way he’s never been captured before – well, we can certainly say she’s done her homework on the man. She’s studied Gurov well, after all, at long range and at short, having walked up and down the esplanade for some time before sitting down next to him, and over the following week she has studied him at very close range.

Maybe, after spending this week together, she likes him. Maybe she just sees something in him she wants. Maybe it’s both. Either way it is at any rate possible to read Anna’s behavior going forward as being at least partly calculating. Figuring Gurov for a serial adulterer (and he is), she decides – or is intuitively moved, if we want to moderate her agency – to give him what he can’t get anywhere else: innocence. In other words, unknowing. And it works. For the weary Gurov, there had been plenty of other women:

…very beautiful, frigid women, across whose faces would suddenly flit a rapacious expression…no longer young, capricious, unreflecting, domineering, unintelligent, and when Gurov grew cold to them their beauty aroused his hatred, and the lace on their lingerie seemed to him to resemble scales.

But here there was the timidity, the angularity of inexperienced youth, a feeling of awkwardness; and there was a sense of embarrassment, as though someone had suddenly knocked at the door.

And further,

Anna Sergeyevna, “the lady with the pet dog,” treated what had happened in a very peculiar way, very seriously, as though it were her fall – so it seemed, and this was odd and inappropriate. Her features drooped and faded, and her long hair hung down sadly on either side of her face; she grew pensive and her dejected pose was that of a Magdalene in a picture by an old master.

She is the perfect picture of a fallen woman, all right. Anna goes on to play her part – if it is a part: (“How can I exonerate myself? No. I am a bad, low woman…”). Gurov resists briefly (“already bored with her; he was irritated by her naïve tone”) but as she presses her advantage (“‘Believe me, believe me, I beg you,’ she said, ‘I love honesty and purity, and sin is loathsome to me'”) he gives in. He’s hers now, and he’ll follow her to the end of the earth.

Note that, and not for the last time, she confuses him – why is she treating this matter so seriously? Doesn’t she know how to behave? Doesn’t she know such a thing can’t be taken for more than it is? Doesn’t she know she’s supposed to be cynical and worldly?

Well, maybe she is worldly – so worldly Gurov can’t see it. Like a three-dimensional creature intervening in Flatland, she can see around corners and into rooms from above, and as Gurov tries to make sense of her, he can make his judgments only on a partial understanding.

The romance is now well-established, but Anna continues to play her role:

Complete idleness, these kisses in broad daylight exchanged furtively in dread of someone’s seeing them, the heat, the smell of the sea, and the continual flitting before his eyes of idle, well-dressed, well-fed people, worked a complete change in him; he kept telling Anna Sergeyevna how beautiful she was, how seductive, was urgently passionate; he would not move a step away from her, while she was often pensive and continually pressed him to confess that he did not respect her, did not love her in the least, and saw in her nothing but a common woman. Almost every evening rather late they drove somewhere out of town, to Oreanda or to the waterfall; and the excursion was always a success, the scenery invariably impressed them as beautiful and magnificent.

Magnificent!

At this point, with Anna having consolidated her gains, the stakes increase. If Anna is interested in continuing the romance, and possibly, eventually, using Gurov to get out of S—-, then the question becomes – how to transfer the romance intact back to civilization, back to their usual lives?

Now evidence grows thin on the ground, and we are left increasingly to our own surmisings. The more straightforward clues (Anna’s approach, the mysterious flowers) fall away, as though Chekhov himself has become undecided on the matter of Anna’s motivations, or as though he wants to suggest that for Anna, matters have become complicated, that her motivations have become uncertain even to herself. Maybe she fears her plan is actually going to work – and then what? Maybe she’s afraid of her feelings for Gurov, and runs from them. Or maybe Chekhov wants to cover his tracks, to introduce uncertainty in us; maybe he fears we’re beginning to see through his mechanisms.

The State Drama Theatre of Tbilisi performs a stage adaptation of The Lady with the Pet Dog (dir. Levan Tsuladze) in Israel. This version uses puppets to present an alternate, fantastic version of what is happening: another point of view

On the other hand, it is still possible to read her actions as – at least in part – the execution of a carefully considered operation. We may perhaps deduce that, given what the story has shown us about her to this point, Anna is now going to gamble. The surest way to transfer the romance intact, she perhaps decides, is to end it abruptly:

They were expecting her husband, but a letter came from him saying that he had eye-trouble, and begging his wife to return home as soon as possible. Anna Sergeyevna made haste to go.

We may catch in this a whiff of the atomized Anna. How indeed does Gurov know Anna’s husband is expected? When and where does this letter appear? Where is the envelope, the weeping as she reads it, the despairing toss of the letter into the fire? These scenes do not exist. In fact Chekhov glides smoothly over this moment without comment. And since at this point we can’t trust Gurov to see what’s happening in front of his own nose, we may be justified in suspecting there’s actually no letter, and that Anna has engineered the whole thing – just as she (perhaps) engineered the moment at the pier. Anna is, perhaps fittingly, firm on what is to happen next:

She was not crying but was so sad that she seemed ill, and her face was quivering.

“I shall be thinking of you – remembering you,” she said. “God bless you; be happy. Don’t remember evil against me. We are parting forever – it has to be, for we ought never to have met. Well, God bless you.”

And Gurov? Has the hook been planted? Well, he thinks he’s fine:

The train moved off rapidly….Left alone on the platform, and gazing into the dark distance, Gurov listened to the twang of the grasshoppers and the hum of the telegraph wires, feeling as though he had just waked up4. And he reflected, musing, that there had now been another episode or adventure in his life, and it, too, was at an end, and nothing was left of it but a memory.

So the knowing cad has had his fun. And alas, Anna’s (possible) gamble appears to have failed. But wait:

He was moved, sad, and slightly remorseful: this young woman whom he would never meet again had not been happy with him; he had been warm and affectionate with her, but yet in his manner, his tone, and his caresses there had been a shade of light irony, the slightly coarse arrogance of a happy male who was, besides, almost twice her age.5 She had constantly called him kind, exceptional, high-minded; obviously he had seemed to her different from what he really was, so he had involuntarily deceived her.

This is the best Gurov can do. Lacking a critical piece of information – that Anna is herself an independent agent, and full of her own intention – his analysis is wrong, or at least incomplete. Yet his point of view is, for all that, more or less coherent: from where he’s standing, he’s drawing some reasonable conclusions. Epicycles, deferents, equants — not seeing that his assumptions are insufficient, not seeing Anna at work, he cannot account for his feelings (sorrow, remorse) any other way.6 And we notice this particularly as he makes no conscious connection between these thoughts and the next two paragraphs, which close section II:

Here at the station there was already a scent of autumn in the air; it was a chilly evening.

“It is time for me to go north, too,” thought Gurov as he left the platform. “High time!”

In other words – Hey, Anna, wait up!

In Part III, Gurov’s cluelessness continues. After a relatively quiet period back in Moscow he finds himself increasingly obsessed with the memory of Anna. He can’t sleep:

And he had a headache….And the following nights too he slept badly; he sat up in bed, thinking, or paced up and down his room. He was fed up with his children, fed up with the bank; he had no desire to go anywhere or to talk of anything.

At this point, he lies to his wife and takes a trip to Anna’s town of S—-, driven by forces he doesn’t understand (“What for? He did not know, himself.”) And then the famous details in the hotel room:

…at the hotel [he] took the best room, in which the floor was covered with gray army cloth, and on the table there was an inkstand, gray with dust and topped by a figure on horseback, its hat in its raised hand and its head broken off…

Without haste Gurov made his way to Staro-Goncharnaya Street and found the house. Directly opposite the house stretched a long gray fence studded with nails.

“A fence like that would make one run away,” thought Gurov, looking now at the fence, now at the windows of the house.

The guy is still trying to make sense of things. Clues, there must be clues. Staring hopelessly at the inkstand, the floor, the nails in the fence, his vision is limited to his immediate surroundings, his forensic capabilities hopelessly, hilariously misapplied. It must be the fence! The fence is to blame, surely!

Poor Gurov.

In S—, he waits for her to appear, walking up and down outside her house. She doesn’t show up. So:

He went back to his hotel room and sat on the couch for a long while, not knowing what to do, then he had dinner and a long nap.

“How stupid and annoying all this is!” he thought when he woke and looked at the dark windows: it was already evening. “Here I’ve had a good sleep for some reason. What am I going to do at night?”

The “for some reason” is a dead giveaway, of course: there’s something here he’s not getting.7 He’s slept well because he’s finally near Anna again, but he has no understanding of this. And when he finally sees her at the theater that night – well, here’s what all the fuss is about:

She sat down in the third row, and when Gurov looked at her his heart contracted, and he understood clearly that in the whole world there was no human being so near, so precious and so important to him; she, this little undistinguished woman, lost in a provincial crowd, with a vulgar lorgnette in her hand, filled his whole life now…

So he can see her, all right – vulgar, little, undistinguished, provincial – but he can’t make sense of what he sees. Is he in love with her? Possibly. Does he know why? No. There are some things he doesn’t know, and never will.

And Anna? Well, maybe she’s forgotten him. Maybe she’s lived the few months away from Gurov in a state of increasing relief, having fled (perhaps voluntarily, having faked the letter?) a situation in Yalta that had grown too hot to handle. Maybe she chickened out, deciding she had too much to lose even in her wanker of a husband. After all, her reaction to Gurov when he appears is one of convincing displeasure:

She glanced at him and turned pale, then looked at him again in horror, unableto believe her eyes, and gripped the fan and the lorgnette tightly together in her hands, evidently trying to keep herself from fainting. Both were silent.

But there’s that lorgnette again, and she’s fooled Gurov before, hasn’t she? (Or has she?) Does Chekhov send us a hint a little later, as the lovers part?

She pressed his hand and walked rapidly downstairs, turning to look round at him, and from her eyes he could see that she really was unhappy.

But this is Gurov seeing her. Silly old half-dense Gurov. He has got her very wrong before, has he not? And this is a look that she sends him on purpose, over her shoulder –is it intentionally loaded with meaning? Has she, in fact, been waiting for this moment all along, rehearsing it, even? (The last time she acted this convincingly, down at the pier – if it was an act! – he followed her back to her hotel room.)

Or is it all of the above? Has she been privately, deliciously rehearsing for a longed-for moment she has dearly hoped would never come?

Oh, dear, we have gone very far afield now – way out here, all is surmise. Whatever Anna’s understanding by this point, she’s worlds beyond Gurov – who, by the end, is still struggling to make even the most basic sense of things. Having come all this way, he is still trying to unfold his map:

It was plain to him that this love of theirs would not be over soon, that the end of it was not in sight….The shoulders on which his hands rested were warm and heaving. He felt compassion for this life, still so warm and lovely, but probably already about to begin to fade and wither like his own. Why did she love him so much? [Yeah, why?]….Only now when his head was gray had he fallen in love, really, truly – for the first time in his life.

But it’s a romance, if it is one, colored by a very Anna-like need for planning and for strategy. The story ends on its famously inconclusive note:

Then they spent a long time taking counsel together, they talked of how to avoid the necessity for secrecy, for deception, for living in different cities, and not seeing one another for long stretches of time. How could they free themselves from these intolerable fetters?

“How? How?” he asked, clutching his head. “How?”

And it seemed as though in a little while the solution would be found, and then a new and glorious life would begin; and it was clear to both of them that the end was still far off, and that what was to be most complicated and difficult for them was only just beginning.

Note the miraculously subtle dance this last sentence peforms. It belongs to Gurov first: “And it seemed as though in a little while the solution would be found, and then a new and glorious life would begin” —

But how, G? Must…think…harder!

And then the sentence marvelously becomes both of theirs, from their very different perspectives: “it was clear to both of them that the end was still far off, and that what was to be most complicated and difficult for them was only just beginning.” It is Anna’s first and only invasion of the point of view, and it is here, at last, perhaps, that Chekhov just minutely tips his hand to us. Anna has work yet to do; if she is to continue, if she is to make her way forward with Gurov, she faces the prospect, now, of not only leaving her husband but also extracting Gurov from his family and his marriage. Gurov must undergo the extraction, with only ignorance as his anaesthetic. This will not prevent a good deal of pain. And naturally Anna will feel it too – perhaps all the more, as the instigator and conscious creator of the situation.

It’s Chekhov’s genius that puts these characters – Anna only half-knowing, Gurov practically unknowing – together at the end, neither able to effect the change they each desire. And it’s part of his genius, too, to leave us not quite sure of what’s transpired. And thinking, as perhaps he means us to, that it doesn’t matter what you observe, or don’t observe, or how carefully you plan – you’ll still never know everything.

We can of course remember this about our characters – that to deliver them into complete understanding probably isn’t what we’re aiming for. More usefully we can also remember this about ourselves as writers – that our own ignorance can serve as a useful model for the uncertainty we wish to deliver to our characters. And furthermore – and maybe best of all – we can remember that if something puzzles us, it’s an excellent indication we’ve discovered a subject worth writing about. We write about what puzzles us, after all. We are compelled to write about those moments in our lives, or the lives of others, that we just don’t understand. Stories powered by mystery and uncertainty can produce powerfully involving, deeply human effects.

And this is key. We are all, finally, hopelessly, doomed to be Ptolemy. But we’re all trying to be Copernicus. It’s in the gap between those two states that the most interesting things happen.

We might even be moved to amend the old-fashioned dictum. Maybe it’s not write what you know. Maybe it’s really write what you don’t know, because what you know ain’t much. At least not as much as Chekhov.

Endnotes

1. Other outstanding examples include John Cheever‘s “Goodbye My Brother”, in which the narrator literally fights to remain in his state of fragile ignorance, and Alice Munro‘s unsurpassed “Family Furnishings” (from Hateship, Friendship, Courtship, Loveship, Marriage), in which the narrator recounts with brutal clarity her own journey from ignorance to understanding, lashing herself mercilessly all the way to a devastating conclusion: “This was what I wanted, this was what I thought I had to pay attention to, this was how I wanted my life to be.” Emphasis on thought, as in I thought so, but I was wrong.

2. Encountered her, that is.

3. Much of the evidence about Anna’s motivation is by nature circumstantial, and at some point we will pass over from reasonable surmise into unreasonable, or at least unsupportable, deduction. The evidence has to be circumstantial, though, because Gurov remains outside the main stream of knowing in this story. Even the reductive, delimited title, which has always been subtly bothersome (and not just because of the Lap/Pet translation problem, and the – for Chekhov – heavyhanded suggestion of Gurov’s subservience) seems, now, to be indicative of Gurov’s short-sightedness, his inability to see beyond the immediately apparent. Sure, Anna has a dog: we know that right away. Indeed it’s literally the first thing Gurov knows about her. The title suggests that for Gurov, this is as far as his understanding reaches. The pervasive imagery of light penetrating darkness, Anna’s lost lorgnette, the repeated insistence on metaphors involving clarity of vision – all become helpfully suggestive in this regard.

4. As perhaps he has.

5. In other words, beyond Anna’s grasp; she cannot hope to meet his level of sophistication.

6. Facing off against Chekhov here we may begin to feel queasily like Gurov. Wrestling an entity capable of superior acts of imagination, we are bound to take the last fall – and leave the mat not sure exactly what’s just happened.

7. The “for some reason” tactic is too often used by authors who need to get from one place to another and cannot be bothered with even a minimal accounting. A character can say “for some reason” as often as he wants; an author should be expected capable of producing an explanation, as is the case here. If Gurov is in Flatland and Anna is the three-dimensional intervener, Chekhov is the four-dimensional creature who inhabits a world beyond even Anna’s comprehension.

About Michael Byers

Michael Byers is the author of The Coast of Good Intentions, a book of stories, and Long for This World, a novel. His first book was a finalist for the PEN/Hemingway Award and won the Sue Kaufman Prize from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, among other citations. A former Stegner Fellow at Stanford, he teaches creative writing at the University of Michigan. His new novel will appear next year from Henry Holt.

Further Resources

Tales of Chekhov (trans. Constance Garnett)

– Read a free translation of “The Lady with the Pet Dog” via Project Gutenberg. Here, read by Richard Ford, is an audio excerpt on NPR’s site. For 99 cents, you can download an audio version of the story in Russian at Talking Bookstore.

– Read an excerpt (published here on NPR) from Richard Ford’s essay “Why We Love Chekhov,” from the introduction to Tales of Chekhov

– Support your local independent bookstore by buying a copy of “Ward No. 6” and Other Stories or Tales of Chekhov, which both contain, among many other works, “The Lady with the Dog.”

– In 1960, a film adaptation called Lady with the Dog drew critical praise at Cannes. Click here to learn more about the film, to rent it on Netflix, or to buy a copy.

– For further ruminations on the mystery that is point of view, consider James Wood’s How Fiction Works (discussed on FWR last winter). Also check out Charles Baxter’s essay “Digging the Subterranean” in The Art of Subtext: Beyond Plot, which discusses the work of both Chekhov and Cheever in a related context.