In the conversation …

Cathy Day is a writer and Assistant Professor at Ball State University, where she teaches undergraduate and graduate creative writing courses.

Anna Leahy is a poet and Associate Professor at Chapman University, where she teaches in the MFA and BFA programs and directs Tabula Poetica.

Stephanie Vanderslice is a writer and Associate Professor at the University of Central Arkansas and directs the Great Bear Writing Project of Central Arkansas.

The three authors in this conversation essay contributed to Power and Identity in the Creative Writing Classroom (edited by Anna Leahy), which launched the New Writing Viewpoints series in 2005.

It’s time to get on with creative writing pedagogy. Can creative writing be taught? Yes, we’re not charlatans, though teaching looks different here than in other disciplines. Should college-level teachers of creative writing be practicing writers? Yes. Though being a great writer doesn’t make you a great teacher, creative writing teachers are strengthened by engaging in the practice themselves. What’s the relationship between creative writing and composition studies? While creative writing is not in opposition to composition studies, neither is it a variation of or sub-discipline within composition studies. Should we grade creative writing? If we are working in institutions that require grading, of course. There exist ways to approach the evaluation of students’ skills and written work that can be minimally intrusive on the writing process and even useful. Is the workshop monolithic? No, the workshop is an adaptable model.

Why do thousands of creative writing instructors who teach courses professionally — who speak and write about teaching creative writing — proceed as if this growing body of pedagogy doesn’t exist? We need this conversation — we need it now — to examine the current state of creative writing pedagogy and propose several areas for further investigation. Let’s get started.

Conversation

Anna Leahy: Some of the body of knowledge in creative writing as a field is pedagogical, some verges on “how to,” and some is akin to literary scholarship. Our body of knowledge is the equivalent of what other fields call theory. It’s tricky to call it theory, though, because we are a practice discipline.

Anna Leahy: Some of the body of knowledge in creative writing as a field is pedagogical, some verges on “how to,” and some is akin to literary scholarship. Our body of knowledge is the equivalent of what other fields call theory. It’s tricky to call it theory, though, because we are a practice discipline.

I recently read James Wood’s How Fiction Works1 and Sven Birkerts’s The Art of Time in Memoir.2 Wood analyzes third-person close point of view, for example, as “free indirect style,” grasping that author and narrator share certain sentences. He’s not just offering a tried-and-true textbook definition, but adding to the understanding of this element of fiction. Birkerts discusses, among other things, the difference between autobiography—a kind of historical writing—and memoir as creative nonfiction. These examples are theoretical and similar to literary scholarship. It’s not the New Critical close reading; it’s reading closely from the writer’s perspective.

I recently read James Wood’s How Fiction Works1 and Sven Birkerts’s The Art of Time in Memoir.2 Wood analyzes third-person close point of view, for example, as “free indirect style,” grasping that author and narrator share certain sentences. He’s not just offering a tried-and-true textbook definition, but adding to the understanding of this element of fiction. Birkerts discusses, among other things, the difference between autobiography—a kind of historical writing—and memoir as creative nonfiction. These examples are theoretical and similar to literary scholarship. It’s not the New Critical close reading; it’s reading closely from the writer’s perspective.

Cathy Day: This kind of “writing about writing” is what Tim Mayers called “craft criticism” in his book (Re)Writing Craft. He defines this body of work as “critical prose written by self- or institutionally identified ‘creative writers” in which “a concern with textual production takes precedence over any concern with textual interpretation.”3 He includes pedagogy and how-to in this category.

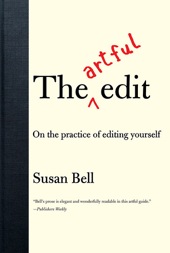

Stephanie Vanderslice: Susan Bell also uses this approach in The Artful Edit,4 which discusses the editing of great literary works in terms of what writers can learn about craft. For example, she introduces the concepts of micro-editing and

macro-editing via a close examination of the actual editing of The Great Gatsby. Interspersed between The Artful Edit’s chapters, moreover, are testimonials from various writers on the ways in which the editing process works for them. Reading this book, I saw great possibilities for structuring a whole course around it and books like it that help student writers develop an editorial consciousness beyond the nuts and bolts. Certainly, I wish I could have had that kind of course in my creative writing education. This growing body of knowledge can shape the future of our academic field.

macro-editing via a close examination of the actual editing of The Great Gatsby. Interspersed between The Artful Edit’s chapters, moreover, are testimonials from various writers on the ways in which the editing process works for them. Reading this book, I saw great possibilities for structuring a whole course around it and books like it that help student writers develop an editorial consciousness beyond the nuts and bolts. Certainly, I wish I could have had that kind of course in my creative writing education. This growing body of knowledge can shape the future of our academic field.

Anna Leahy: We agree that this body of knowledge is growing, but we also agree that there remains resistance to pedagogy in our publications and professional venues.

Anna Leahy: We agree that this body of knowledge is growing, but we also agree that there remains resistance to pedagogy in our publications and professional venues.

Cathy Day: Honestly, I think one reason why more creative writers aren’t engaging in this pedagogy conversation is because of that word: theory. These days, there’s a distinct polarization between the critical and the creative, and this discipline—creative writing pedagogy—sits on that divide. One side thinks we aren’t theoretical enough, and the other side thinks we’re too theoretical. We need to bring more writers from both sides into this space.

A few months ago, I had the opportunity to hear James Kincaid speak about this subject. He’s the Aerol Arnold Chair in English and Professor of English at USC, a serious literary scholar who also writes and publishes fiction. He said that bridging the critical/creative divide doesn’t necessarily mean that writers in academia must learn to “talk theory,” but rather (or also) that English departments should incorporate creative writing into the foundational experience of English studies.

Stephanie Vanderslice: When thinking about the place of creative writing in English studies, it’s important to remember that the role of creative writing varies from institution to institution, from a general education requirement at some schools that encompasses thousands of students, to a small, single course requiring instructor permission to enroll. This same variability is present in the range of courses available; smaller departments may have one multi-genre creative writing course, perhaps one in fiction and poetry, larger departments with a creative writing major may have a large number, including genre-specific workshops, forms courses, new media courses, and so forth. We shouldn’t talk of the field as if it’s uniform throughout.

Whether creative writing should be foundational in English studies deserves further examination. It would be worth looking at the benefits of this approach through the perspective of the professors who teach such foundational courses and the students who take them. In the UK, creative writing is definitely considered one of many lenses through which English majors study literature, but I’m not sure they’ve written about this practice much; the benefits seem to be rather assumed there.

they’ve written about this practice much; the benefits seem to be rather assumed there.

As a member of a writing department that is, in my university, separate from the English department, I would advocate for a creative writing course in the general education curriculum. Books like Daniel Pink’s A Whole New Mind5 convince me that in the post-information age, the ability to convey information via a compelling sense of narrative and story will be a critical skill for all college students. Examples of this phenomenon are everywhere; from digital storytelling to blogging, narrative is at the core of information in the 21st century.

Anna Leahy: The rich variety across institutions and the continuing growth of programs extend what has already been deemed a boom time for creative writing. Mark McGurl’s recent book The Program Era opens with the assertion “that the rise of the creative writing program stands as the most important event in postwar American literary history.”6 Some see the ubiquitous creative writing course as the downfall of literature. But Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class,7 though it isn’t about creative writing per se, argues that creative thinking is crucial for our future world.

Anna Leahy: The rich variety across institutions and the continuing growth of programs extend what has already been deemed a boom time for creative writing. Mark McGurl’s recent book The Program Era opens with the assertion “that the rise of the creative writing program stands as the most important event in postwar American literary history.”6 Some see the ubiquitous creative writing course as the downfall of literature. But Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class,7 though it isn’t about creative writing per se, argues that creative thinking is crucial for our future world.

Cathy Day: While some see the exponential growth of creative writing programs and online writing communities as a harbinger of doom, I think it’s a cause for celebration that so many people feel authorized to write and are interested in learning to do so. As Richard Hugo wrote in The Triggering Town, “A creative-writing class may be one of the last places you can go where your life still matters.”8

Anna Leahy: That idea of mattering reminds me of an article in The Writer’s Chronicle, in which Steve Healey scrutinizes the position of creative writing in the academy. He ignores much of existing pedagogy work: “the field has tended to avoid thinking about how it teaches.”9 But I’m glad he asks us to think about dreaded capitalism, whether our teaching goals match students’ life goals, and how other fields can benefit from our practices. We still need more documentation of what’s really happening in our programs and classrooms. We matter, but how exactly?

Anna Leahy: That idea of mattering reminds me of an article in The Writer’s Chronicle, in which Steve Healey scrutinizes the position of creative writing in the academy. He ignores much of existing pedagogy work: “the field has tended to avoid thinking about how it teaches.”9 But I’m glad he asks us to think about dreaded capitalism, whether our teaching goals match students’ life goals, and how other fields can benefit from our practices. We still need more documentation of what’s really happening in our programs and classrooms. We matter, but how exactly?

Cathy Day: One thing I enjoy about being on Facebook and being “friends” with lots of other creative writing teachers is sharing information about what we do in the classroom, but occasionally swapping syllabi or lesson plans isn’t enough. A few months ago I wrote a 5,000-word essay about moving from writing stories to writing books. It was part craft, part form/genre theory, part pedagogy. I faced two problems. One, there was no clear body of knowledge within which to frame my discussion, and two, I had little idea where to send this essay. We need more journals, more opportunities to talk to each other professionally about teaching.

Stephanie Vanderslice: Two venues for this sort of work are New Writing published out of the UK, and the Australian online journal Text. There are some great conversations happening about creative writing in these journals, as well as in an online journal about teaching creative writing in the UK called cwteaching.com.10 Some up-and-coming American writers have had essays published there, including Kate Kostelnik; they are an incredible resource and they’re readily available online. The articles in them are just what we’re talking about: not just about craft, but about teaching craft. We need to develop an awareness of those venues here in the United States.

Stephanie Vanderslice: Two venues for this sort of work are New Writing published out of the UK, and the Australian online journal Text. There are some great conversations happening about creative writing in these journals, as well as in an online journal about teaching creative writing in the UK called cwteaching.com.10 Some up-and-coming American writers have had essays published there, including Kate Kostelnik; they are an incredible resource and they’re readily available online. The articles in them are just what we’re talking about: not just about craft, but about teaching craft. We need to develop an awareness of those venues here in the United States.

Anna Leahy: I’m glad we’re talking across oceans. But because the British and Australian educational systems are different from ours, it’s also important to develop visible venues here too. Pedagogy is a journal about English studies generally that is open to pieces about creative writing. AWP launched a spot for some of this work a few years ago; it’s a small batch of essays in the members’ e-link section of the website.

Anna Leahy: I’m glad we’re talking across oceans. But because the British and Australian educational systems are different from ours, it’s also important to develop visible venues here too. Pedagogy is a journal about English studies generally that is open to pieces about creative writing. AWP launched a spot for some of this work a few years ago; it’s a small batch of essays in the members’ e-link section of the website.

Stephanie Vanderslice: In the absence of our own national journal devoted to creative writing pedagogy, College English and College Composition and Communication have also provided some space for these discussions. But creative writers shouldn’t have to rely on those venues exclusively.

Cathy Day: This issue isn’t solely related to the lack of journals out there, of course. There exists another reason why writers who teach creative writing are not more fully engaged in these issues: they can’t afford to be, because at some institutions, working in this area doesn’t “count” towards tenure and promotion in the same way as publishing creative work.

Stephanie Vanderslice: Joseph Moxley has a wonderful essay in Does the Writing Workshop Still Work?,11 in which he talks about why he hasn’t engaged much in creative writing pedagogy since he published Creative Writing in America12 more than twenty years ago. Apparently, his institution told him he would get zero credit for editing that important book and that he should spend his time on more established critical disciplines for promotion and tenure.

I am fortunate to be at an institution where I am encouraged to do both creative and critical work. We need to remember, as we discuss professional and pedagogical issues, that different institutions have different missions and environments. We need to continue to legitimize the field of creative writing pedagogy. It shouldn’t be in competition with the rest of our pursuits as writers.

Even so, teacher-writers are still responsible for knowing what’s going on. At my institution, for example, the teaching narratives in our promotion and tenure packages must be grounded in the pedagogy of the field. Many institutions require these sorts of teaching descriptions from individuals. These kinds of documents, then, could also demonstrate a teacher-writer’s engagement with his or her teaching discipline.

Anna Leahy: I wouldn’t encourage any creative writing teacher to devote all her professional development time to pedagogy scholarship, at the complete expense of, say, poems or a novel. But even in institutions that value publication over teaching, most of us are teaching regularly. As long as we’re teaching, we remain responsible for articulating not just what we do, but also how and why we teach the way we do.

Anna Leahy: I wouldn’t encourage any creative writing teacher to devote all her professional development time to pedagogy scholarship, at the complete expense of, say, poems or a novel. But even in institutions that value publication over teaching, most of us are teaching regularly. As long as we’re teaching, we remain responsible for articulating not just what we do, but also how and why we teach the way we do.

Stephanie Vanderslice: In articulating what we do and how we do it, one of the most interesting and, perhaps, important issues to discuss as we go forward are the ways in which we respond to students’ creative writing. There exists much more to examine about how we respond—in writing and orally—and especially why. What leads to the most improvement? This issue is an old staple, in some ways, but it is newly complicated by the rise of program assessment as part of institutional accreditation over the last decade or two.

As a faculty member in an independent writing program, I have been occupied with assessment from the beginning. Our program was founded in 1996 under some controversy, so the issue of whether we were producing “results” was a factor early on. We’ve looked at the issue in a number of different ways and have finally settled on an exit portfolio system from our general education writing courses, our writing major, and now our creative writing major. I give our Assessment Committee significant credit; this is not an easy issue to grapple with, and many faculty can be very suspicious of the A-word. While we’ve finally come up with assessment plans, they are constantly evolving as we continually ask ourselves what we are actually assessing and what we want to see in our students’ work. That’s the key to assessment, I think. Once formed, the models require ongoing reflection and fine-tuning.

Cathy Day: I hope we aren’t losing readers at this point, just because we mentioned assessment. Stick with us, reader, because we’re covering a lot of ground.

Assessment has been good for creative writing programs, because it’s forced what I’ll call first-generation writers in academia to talk openly about what they’re doing in the classroom and why. The three of us represent that second generation, whose journey into academic teaching was informed by our shared experience teaching composition as TAs. And it’s fallen on our generation to handle the assessment tasks.

I’ve observed this process at two different schools, and both times, the experience was ultimately enriching. Once you get past the jargon—learning goals, outcomes, rubrics, and matrices—you discover commonalities among colleagues and develop a shared sense of purpose. About ten years ago, I was teaching at a college that ramped up its assessment at the same time that I was developing a creative writing minor. I had to articulate a rationale for course levels, and that document, created out of bureaucratic necessity, became a list of craft proficiencies—basic, intermediate, and advanced—that I’ve used every semester since then to explain my expectations and grading policies. My students appreciate this transparency, and it’s allowed for a better learning environment in which they can thrive. At both schools, we ended up—after some fussing and resistance—with a far more cogent curriculum than the one with which we started.

Anna Leahy: The catalog and syllabus are legally binding documents, so, even just in practical terms, it’s a good idea for us to back them up with what happens in our courses. When creative writing programs were being formed a couple of decades ago, conversations about how it all adds up must have occurred, but discussion fell off, or wasn’t carried on across institutions, and a great deal became taken for granted. Assessment reinvigorates that conversation about pedagogy and the profession.

Anna Leahy: The catalog and syllabus are legally binding documents, so, even just in practical terms, it’s a good idea for us to back them up with what happens in our courses. When creative writing programs were being formed a couple of decades ago, conversations about how it all adds up must have occurred, but discussion fell off, or wasn’t carried on across institutions, and a great deal became taken for granted. Assessment reinvigorates that conversation about pedagogy and the profession.

That said, I have grave concerns about how assessment is practiced, namely that current practices encourage us to loosely apply social science methodology to the arts and humanities. I hesitate to turn to composition studies for guidance because that field is heavily influenced by social science methodology (and also because there’s a practical risk in aligning with a so-called service discipline, or one often without a major). We shouldn’t start with the tools of another trade. Instead, we should begin with issues in our body of knowledge, then develop methods and tools to answer our field’s questions.

Cathy Day: My general impression is that the best way to get so-called cred in academia — and now that, in part, means assessment — is to model ourselves after composition studies, but by doing so, we lose touch with our identity as working artists.

I think we should look outside the English Department and turn to studio art departments for further guidance. As Madison Smartt Bell says in the introduction to his textbook Narrative Design, “The teaching of music and visual art as crafts in some systematic fashion is centuries old; it goes back as far as Renaissance ateliers, even to the medieval guilds. There is no long-standing tradition of guilds or ateliers for fiction writers.”13

Stephanie Vanderslice: As Wendy Bishop would have said, “There’s an essay in that.” We’ve been referencing other arts for years. It’s time for someone to really take a look at how other arts, like music and the visual arts, are taught and how some of these methods might be applied to creative writing. I’ve considered doing it, but I’d love to see a new scholar-writer take it on.

Anna Leahy: Every discipline has its own priorities, and ours tend to be habits of mind. That’s a good reason to talk across the creative arts (or even medicine is a practice discipline, in which advanced students learn by doing). It’s easier to measure, say, acquisition of terminology in biology than to measure thinking for oneself, which Classroom Assessment Techniques14 lists as one of the three top teaching goals English faculty report having. Faculty lead busy lives, so it’s tempting to assess what’s easiest to measure instead of what’s most important. Narrative assessment must be taken seriously.

Anna Leahy: Every discipline has its own priorities, and ours tend to be habits of mind. That’s a good reason to talk across the creative arts (or even medicine is a practice discipline, in which advanced students learn by doing). It’s easier to measure, say, acquisition of terminology in biology than to measure thinking for oneself, which Classroom Assessment Techniques14 lists as one of the three top teaching goals English faculty report having. Faculty lead busy lives, so it’s tempting to assess what’s easiest to measure instead of what’s most important. Narrative assessment must be taken seriously.

AWP has begun to tackle assessment, with some conference panels. Such an organization could provide us with guidance that can be adapted across institutions. I fear we’ll each cobble together something do-able that satisfies given administrators, without taking advantage of doing something really useful for the discipline as a whole.

Cathy Day: Let me step away for a moment to approach the fourth wall—to step outside our conversation with each other. You — YOU, reader of this dialogue — I fear that right about here in this pretty important conversation we’re having about what we do — about what you do for a living — your eyes are glazing over as you encounter words like assessment and rubric. Am I right? Well, how would you feel if your physician skipped the boring stuff at her professional medical conference? How would you feel if the Journal of the American Medical Association stopped publishing because the jargon got too dry to keep doctors’ interest and because they figured each doctor could figure it out on his own?

That’s the sort of thing we’re talking about here. We’re talking about issues that matter. We’re talking about our professional obligations. In common parlance, don’t be part of the problem. Be part of the solution. Okay, let me slip back into the conversation.

Editor’s Note: Slip back into the conversation tomorrow on FWR for the second half of this discussion, including:

- How do different kinds of feedback allow a student to progress in their own goals?

- How can the classroom experience better prepare the writer for the realities of life beyond academia?

- What role should new digital media – video, illustration, sound – play in creative writing programs?

Further Links and Resources

- Interested in reading more about the theory and practice of teaching creative writing? The authors recommend: David Huddle’s The Writing Habit by David Huddle; If You Want To Write: A Book about Art, Independence and Spirit by Brenda Ueland; and Making a Literary Life by Carolyn See.

Citations

James Wood, How Fiction Works, New York: Picador, 2009.

Sven Birkerts, The Art of Time in Memoir, Minneapolis, MN: Graywolf, 2007.

Tim Mayers, (Re)Writing Craft: Composition, Creative Writing, and the Future of English Studies, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005. 33.

Susan Bell, The Artful Edit: On the Practice of Editing Yourself, New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2007.

Daniel Pink, A Whole New Mind: Why Right Brainers Will Rule the Future, New York, NY: Riverhead, 2006.

Mark McGurl, The Program Era, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009.

[Click “Back” on your browser to return to essay]

Richard Florida, The Rise of the Creative Class, New York, NY: Basic Books, 2003.

Richard Hugo, The Triggering Town, New York: W.W. Norton, 1979.

Steve Healey, “The Rise of Creative Writing & The New Value of Creativity,” The Writer’s Chronicle. 41.4.

Creative Writing: Teaching Theory & Practice in cwteaching.com.

Joseph Moxley, Afterword: Disciplinarity and the Future of Creative Writing Studies, Does the Writing Workshop Still Work?, Ed. Dianne Donnelly, Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters, 2010. 230-238.

Joseph Moxley, Creative Writing in America, Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English, 1989.

Bell, Madison Smartt, Narrative Design: Working with Imagination, Craft, and Form, New York: W.W. Norton, 1997. 3.

Thomas Angelo and Patricia Cross, Classroom Assessment Techniques, Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass, 1993.

[Click “Back” on your browser to return to essay]