Editor’s Note: For the first several months of 2022, we’ll be celebrating some of our favorite work from the last fourteen years in a series of “From the Archives” posts.

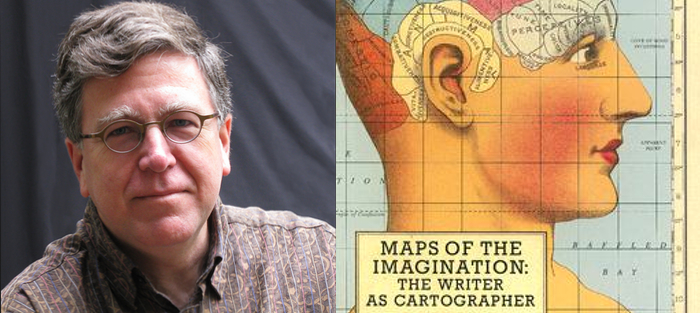

In today’s feature, Peter Turchi turns his analytical powers to the release of information in Thomas Bernhard, Antonya Nelson, Charles D’Ambrosio, and more. This essay was originally published on April 25, 2010.

You know, I order everything.

You know everything I order.

I know everything you order.

You order everything—and I know.

I order everything—and you know.

Everything I order, you know.

Everything I know, you order.

I order you: know everything.

Order everything! I know you.

The most basic level on which the order of information is critical is within the sentence. Syntax creates meaning. It can provide clarity, but it can also create mystery and tension. Mystery and tension, it can create. Created is mystery; also…….tension.

Here is the first sentence of Thomas Bernhard’s novel Correction:

After a mild pulmonary infection, tended too little and too late, had suddenly turned into a severe pneumonia that took its toll of my entire body and laid me up for at least three months at nearby Wels, which has a hospital renowned in the field of so-called internal medicine, I accepted an invitation from Hoeller, a so-called taxidermist in the Aurach valley, not for the end of October, as the doctors urged, but for early in October, as I insisted, and then went on my own so-called responsibility straight to the Aurach valley and to Hoeller’s house, without even a detour to visit my parents in Stocket, straight into the so-called Hoeller garret, to begin sifting and perhaps even arranging the literary remains of my friend, who was also a friend of the taxidermist Hoeller, Roithamer, after Roithamer’s suicide, I went to work sifting and sorting the papers he had willed to me, consisting of thousands of slips covered with Roithamer’s handwriting plus a bulky manuscript entitled “About Altensam and everything connected with Altensam, with special attention to the Cone.”

None of the information in that sentence is difficult to comprehend; but the arrangement of the information is deeply, and intentionally, disorienting. A variety of information passes by that seems quite worthy of being the subject of the sentence—or of a sentence—and of our attention—but the syntax, as well as the length of the sentence, seems to make everything subordinate. We’re confronted with surprising qualifiers: “the field of so-called internal medicine,” “a so-called taxidermist.” There’s even a sort of syntactical joke, via a parenthetical clause: “went on my own so-called responsibility straight to the Aurach valley and to Hoeller’s house, without even a detour to visit my parents in Stocket, straight into the so-called Hoeller garret.” That mention of not taking a detour is a detour on our voyage through the sentence. The end of that journey—the mention of Roithamer’s manuscript–feels oddly anti-climactic. After a rush of relief that the sentence has finally stopped, our first impulse might be to go back and look again at all the things the narrator has alluded to, the narrative premise he’s suggested.

Long sentences, repeated phrases, and unorthodox punctuation are defining elements of Bernhard’s prose. I do not offer it here as a model we should all set off to imitate; personally, I have to work up a certain amount of intellectual energy to engage with Bernhard’s work, which is made more challenging because he isn’t very fond of giving his reader opportunities to stop and reflect. In the edition I own, Correction is 271 pages long. It’s divided into two chapters, each of which consists of a single paragraph.

By all accounts, Bernhard was a pretty miserable fellow, a fact that offers some consolation to the reader seventy or eighty pages into the first paragraph. Misery does love company; so I’ll offer you one more sentence from the book, a slightly shorter and much more direct one. Sixteen pages into the novel, our narrator is standing in Hoeller’s garret, contemplating the task ahead of him—going through his deceased friend’s papers and, more important, trying to comprehend his life’s work. The narrator says,

As I stood there looking around Hoeller’s garret it was instantly clear to me that my thinking would now have to conform to Hoeller’s garret, to think other than Hoeller-garret-thoughts in Hoeller’s garret was simply impossible, and so I decided to familiarize myself gradually with the prescribed mode of thinking in this place, to study it so as to learn to think along these lines, entering Hoeller’s garret and learning to adjust, to entrust and subject oneself to these mandatory lines of thought and make some progress in them is not easy.

We understand that Bernard, the author, is talking to us, his reader, about the challenge he knows he’s given us; and he is, in his way, offering a sign of compassion.

It’s often easier to see something in its most extreme form. It may be obvious that to read Bernhard we must, like his narrator, “familiarize ourselves with the prescribed mode of thinking in this [book], to study it so as to learn to think along those lines…because to entrust and subject oneself to these mandatory lines of thought and make some progress in them is not easy.” This is what many of us discovered for ourselves as we learned to read “difficult” writers, which, depending on your own tastes, could mean the James Joyce of Ulysses, the Faulkner of Absalom! Absalom!, Proust, Pynchon, Hemingway, or even, for some readers, Alice Munro or Mavis Gallant. This, too, is something we try to help our students overcome—the resistance to engaging with new ways of conveying information through language, which is to say new—and so difficult, at least initially–ways of thinking.

But this adjustment we make as readers to a writer’s delivery of information isn’t necessarily a matter of difficulty. Fans of Jane Austen admire her not so much for her plots but for her wit, which relies heavily on what she chooses to tell us when, and how she chooses to tell it to us (“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” The combination of bold assertion and the passive voice makes the narrator present yet remote; and “must be in want of a wife” falls into place with the timing of a punch line.). The same holds true for Dickens and, in our day, writers as wide-ranging as David Foster Wallace, Charles Baxter, Don DeLillo, Lydia Davis, and Richard Russo—to read their work is to enter a world defined by, among other things, the particular way they convey information through the arrangement of language.

But this adjustment we make as readers to a writer’s delivery of information isn’t necessarily a matter of difficulty. Fans of Jane Austen admire her not so much for her plots but for her wit, which relies heavily on what she chooses to tell us when, and how she chooses to tell it to us (“It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune must be in want of a wife.” The combination of bold assertion and the passive voice makes the narrator present yet remote; and “must be in want of a wife” falls into place with the timing of a punch line.). The same holds true for Dickens and, in our day, writers as wide-ranging as David Foster Wallace, Charles Baxter, Don DeLillo, Lydia Davis, and Richard Russo—to read their work is to enter a world defined by, among other things, the particular way they convey information through the arrangement of language.

I’ll offer two more examples, both from work that will probably seem much less challenging, much more immediately accessible, but which is no less aware of its sentence-level strategy than Bernhard’s novel.

Within a sentence, diction can be used to clarify or to strategically obscure. The first sentence of Antonya Nelson’s short story “Strike Anywhere,” is, “This was the next time after what was supposed to be the last time.”

Again, there’s nothing about that language or its arrangement that is difficult to comprehend; the trouble is, we’ve got signifiers, but no specific content. “This was the next time after what was supposed to be the last time.” What is “this”? we think. The next time for what? The last time for what? All we know for sure is that “this” is an occasion, and it’s significant because it wasn’t supposed to happen.

The next sentence puts us at ease by offering clear and explicit information—two characters and a bit of action: “The father parked at the curb before the White Front, and the boy found himself making a prayer.”

So we’ve got a boy and his father, and the boy seems to be worried. The tension is maintained, but so is the mystery—we still don’t know what’s going on, or why it’s important. The boy’s worry mirrors our own unease about not knowing what the narrator is referring to.

The paragraph continues, “It was Sunday, after all, and this was what his mother did when faced with his father’s stubborn refusal to do what he said he’d do. Or not do what he said he’d not do.”

That first sentence created a desire to know certain information: What is this significant event? And why isn’t it supposed to happen? We still don’t have an answer, but the context for the question is becoming increasingly clear—so while we’re eager to have those initial questions answered, we’re content to wait a little longer, because we’re getting what seems to be important information. By the third paragraph, when we learn the father and son are parked in front of a bar, we think we’ve got a clue; but by that time the focus of the narrative is no longer the simple fact of what’s going on, but the difficult situation the boy is in, and his father’s obliviousness, or self-interest, and the mother’s influence, or lack of it. The story has shifted our attention from a minor mystery to a more significant one. On some level or another nearly every successful story works this way, leading us from one mystery to another, like stepping stones across a river.

That first sentence created a desire to know certain information: What is this significant event? And why isn’t it supposed to happen? We still don’t have an answer, but the context for the question is becoming increasingly clear—so while we’re eager to have those initial questions answered, we’re content to wait a little longer, because we’re getting what seems to be important information. By the third paragraph, when we learn the father and son are parked in front of a bar, we think we’ve got a clue; but by that time the focus of the narrative is no longer the simple fact of what’s going on, but the difficult situation the boy is in, and his father’s obliviousness, or self-interest, and the mother’s influence, or lack of it. The story has shifted our attention from a minor mystery to a more significant one. On some level or another nearly every successful story works this way, leading us from one mystery to another, like stepping stones across a river.

This is a useful example because we might sometimes tell ourselves that every sentence in a story should be beautiful, or finely wrought, or exquisitely detailed, or that it should present the reader with a new and brilliant figure of speech. But that first sentence–“This was the next time after what was supposed to be the last time.”—is one I might be inclined to mark in a student manuscript, scrawling something like “vague’ or “confusing”—because it would probably be followed by similarly abstract assertions. The combination of the abstract and the concrete, coupled with the deliberate release of contextualizing information, is what makes this writing strategic. In that first sentence, Nelson is not trying to find her way into the story—she’s deliberately creating questions she knows we’ll want answers to.

Simply omitting information doesn’t create a sense of mystery or tension; you don’t know my shoe size, but you don’t care. The reader needs to be made to want to know what’s being withheld or obscured. If the reader isn’t provoked to want to know more, the story has no forward momentum, no sense of urgency.

Like Nelson, Charles D’Ambrosio writes clear and precise prose which moves seamlessly from the colloquial to high diction and back. For our purposes I’d like to isolate a few sentences in his story “The Scheme of Things” to show how they subtly prepare the reader for a bit of trickery. The story begins with description of one of the two main characters:

Lance vanished behind the white door of the men’s room and when he came out a few minutes later he was utterly changed. Gone was the tangled nest of thinning black hair, gone was the shadow of beard, gone, too, was the grime on his hands, the crescents of black beneath his blunt, chewed nails. Shaving had sharpened the lines of his jaw and revealed the face of a younger man….He looked as clean and bland as an evangelist.

That first sentence, “Lance vanished behind the white door of the men’s room and when he came out a few minutes later he was utterly changed,” and especially the use of “vanished” and “utterly,” might suggest something of a magic trick. Lance didn’t simply open the door, or go into the men’s room—he “vanished.” He didn’t just look different; he was “utterly changed.” The next sentence is a nice bit of sleight-of-hand, as D’Ambrosio tells us what Lance looked like earlier by telling us what’s missing; Gone was the black hair, gone was the beard and so on. That emphasis on what has disappeared makes ominous the otherwise simple statement, “He looked as clean and bland as an evangelist.” One thing we know by this point in the first paragraph: Lance is no evangelist; and we suspect he is up to no good.

Having established that possibility, the story introduces the other main character, Kirsten, and the boy at the service station who inspects their damaged car. When the boy goes to get material for a temporary repair, Lance sits on the hood and looks around. We see brown clouds of soil, dust on the leaves of a few dying elms, some trailers across the street, and then this:

One of the trailer doors swung open. Two Indians and a cowgirl climbed down the wooden steps. It was Halloween.

On first reading, this arrangement of information feels like a deadpan joke. The narrator could have told us earlier that it was Halloween—that certainly would have given us a different context for Lance’s transformation. But it would have been a wasted gesture in the first paragraph, given the story’s purposes. Here are those plain and direct sentences again:

One of the trailer doors swung open. Two Indians and a cowgirl climbed down the wooden steps. It was Halloween.

Notice what the second sentence doesn’t say: “Three children, two dressed as Indians and one as a cowgirl, climbed down the wooden steps.” No, the omniscient third person narrator asserts that what exits the trailer are “Two Indians and a cowgirl.” Also absent: the word “costume.”

So on the next page we accept the narrator’s assertion that when Kirsten, the other main character, walks toward the intersection, “Ghosts and witches crossed from house to house, holding paper sacks and pillowcases.” Not children dressed as ghosts and witches, not people in costumes.

The narrator then rewards our close reading by adding to the motif:

The street lights sputtered nervously in the fading twilight…The casual clothes that Lance had bought her in Key Biscayne, Florida, had come to seem like a costume and were now especially flimsy and ridiculous here in Tiffin, Iowa.

Lance vanishes and reappears, looking as bland as an evangelist; Indians and cowgirls and ghosts and witches walk the streets; but Kirsten feels as if her clothes are a costume. Subtext is beginning to take shape, but we have no way to see that the next lines are part of it:

A young girl crossed the road, and Kirsten followed her, She thought she might befriend the girl and take her home….

The interaction with the little girl transpires over the course of two pages; then there’s some other action; and so quite some time passes before we learn that the little girl Kirsten met was actually killed in an accident years ago. She is what some of us might call a ghost.

If there were no preparation for that revelation, the story would feel like a cheat. But from its very first sentence, the story has announced that people are not what they appear to be; and by introducing those two Indians and a cowgirl before we know it’s Halloween, the story has essentially telegraphed the illusion that’s about to follow. Rather than feel tricked, when we realize that the little girl was a ghost, we recognize that the narrator was telling us more than we could understand, withholding information but also drawing our attention to the very thing we should be looking at.

If there were no preparation for that revelation, the story would feel like a cheat. But from its very first sentence, the story has announced that people are not what they appear to be; and by introducing those two Indians and a cowgirl before we know it’s Halloween, the story has essentially telegraphed the illusion that’s about to follow. Rather than feel tricked, when we realize that the little girl was a ghost, we recognize that the narrator was telling us more than we could understand, withholding information but also drawing our attention to the very thing we should be looking at.

At the start I said that the first level at which the release of information is important is within the sentence. But information is significant even on a smaller level. Just two weeks ago, for an undergraduate workshop, the students and I read the draft of a story about a young man required to attend a rehab clinic. The subject is serious and the writer’s treatment of it was serious. But one phrase gave many of us extraordinary delight. It comes when the main character is assessing one of his fellow addicts; we’re told that this young woman suffered from “elf inflicted wounds.”

The artful withholding of a single letter transformed an otherwise mundane tale into a fascinating one. I’m certain I’m not the only reader who immediately pictured a little man digging his pointy ears into the woman’s shin, then returning to his tree to bake more cookies.

But I can hear you now: “That was probably a mistake, a typographical error.” While I went out of my way not to ask the author, the abashed look on his face when someone quoted the phrase, gleefully, makes me suspect you might be right.

So I’ll conclude with what I know is a deliberate omission—this from no less a writer than F. Scott Fitzgerald, and from no less a novel than The Great Gatsby. We all know those wonderful sentences in Gatsby, from “In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since” straight through to “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

But here are a few sentences you probably don’t remember:

“I’m very sad, old sport…Daisy wants us to run off together. She came over this afternoon with a suitcase all packed and ready in the car.” Gatsby shook his head wearily. “I tried to explain to her that we couldn’t do that, and I only made her cry.”

“In other words you’ve got her—and now you don’t want her.”

“Of course I want her,” he exclaimed in horror. “Why—Daisy’s all I’ve got left from a world so wonderful that to think of it makes me sick all over…it’s all so sad because I can’t make her understand…I’m only thirty-two. I might be a great man if I forgot that I once lost Daisy.” (89/90)

Or how about these gems:

“You know, old sport, I haven’t got anything…I thought for awhile I had a lot of things, but the truth is I’m empty, and I guess people feel it. That must be why they keep on making things up about me, so I won’t be so empty. I even make up things myself.” (116/117)

To be fair, it’s not the sentences themselves that are so excruciatingly awful—it’s the content. They make the mistake of directly articulating what is much, much better left unsaid. Which is why Fitzgerald cut them from the final draft. [They appear in the draft published as Trimalchio.]

I offer them to you because it’s heartening to remember that even wonderful writers do some truly dreadful writing. But more important, The Great Gatsby reminds us that narration is an act of translation. We aren’t recording a story, we’re creating it; and a defining element of the creation is the language we use, and our arrangement of it.