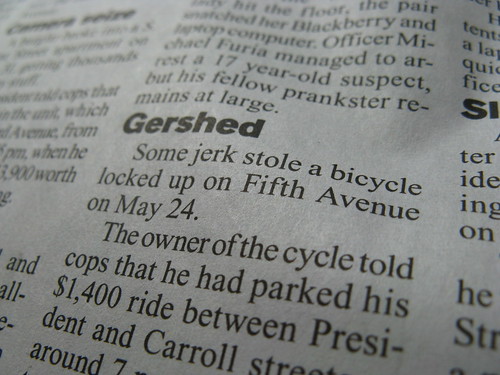

A fallen Nicaraguan dictator, criminal waifs lost in the Pacific Northwest, two police officers who fall in love, and one truly massive earthquake: these are the subjects of Daniel Orozco’s stories, which are as formally unique as they are emotionally revealing.

A fallen Nicaraguan dictator, criminal waifs lost in the Pacific Northwest, two police officers who fall in love, and one truly massive earthquake: these are the subjects of Daniel Orozco’s stories, which are as formally unique as they are emotionally revealing.

Orientation, his long-anticipated story collection recently out from Faber and Faber, shows off this unique set of nimble narrative chops, so it’s no surprise that pieces from the collection have appeared in Best American Short Stories, Best American Mystery Writing, and The Pushcart Prize anthology. In addition, he’s been the recipient of a fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a finalist for a National Magazine Award in fiction. Via phone from his home in Moscow, Idaho, where he is on the fiction faculty at the University of Idaho, Daniel and I talked about craft, teaching, and MFA haters.

Interview

Michael Shilling: Among other writers, you’ve been one of these “best kept secrets” whose collection is deeply anticipated. How does it feel for Orientation to finally be out?

Michael Shilling: Among other writers, you’ve been one of these “best kept secrets” whose collection is deeply anticipated. How does it feel for Orientation to finally be out?

Daniel Orozco: It’s nice. [Laughs.] I never thought I’d get this collection published.

Considering that you’re a short story writer, and how little publishers want to publish short story collections, it’s quite an achievement. Was finding a publisher an arduous process?

For a long time, publishing people told [writers], “Hey, these stories are great, but do you have a novel? Because nobody wants a short story collection.” So yeah, I pretty much gave up on the idea that I’d get the collection published, and that was the reason I started a novel, out of a kind of career necessity. But then I finally found an agent who told me she could sell the collection, but we had to wait until, as she said, the stars lined up. And they did. So it’s just fantastic.

Your stories really run the structural gamut, and those structural choices create different emotional tones and narrative priorities. Taking “Officers Weep” as an example, how do you think those choices affected the way those stories ended up?

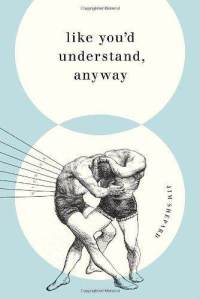

Every story that I write feels like a kind of experiment. The challenge in crafting a story is how to engage a reader emotionally, intellectually, experientially. I’m always looking for some kind of challenge, some kind of structural or narrative constraint to try and figure out. For “Officers Weep,” it was, Can I tell a story that is written in the form of a police blotter? And in a way the structure determines how the story’s gonna go. So yes, I begin with form and then fill in with character and engagement. Jerome Stern talks about the “shapes of fiction,” and I think that’s a good analogy, because I need a shape for the story and then I start figuring out what’s going to happen in it.

That approach is refreshing. I think a lot of writers are afraid of playing with structure because of self-consciousness, these false distinctions between the “realistic” and the “experimental,” and if they play around with structure it’ll be seen as a gimmick. As if a gimmick is always bad.

Right! I mean, the story “Orientation” is a gimmick. You can only do it once for a limited amount of pages, and the same goes for “Officers Weep” because I can’t do a series of stories structured as police blotters. But so what? All that matters is that a story, whatever the structure, must be grounded in the humane.

Agreed. Other stories in the collection also have specific structural choices. Like, in “Somoza’s Dream,” we jump around in time somewhat, but it still manages to have a pretty tense momentum. How did that story come together?

The first drafts of “Somoza’s Dream” were much more expansive. There were flashbacks to Somoza’s childhood, for example, so I was going to move back and forth in time more. But it read more as a biographical story, and I decided to abandon that thematic approach because I figured out that I was trying to make this man who wasn’t very interesting more interesting that he was. So once I gave up this autobiographical framing, I started populating the story with people around him. I knew that I wanted to begin with the assassination and then return to it, but that was pretty much the structural demand I made upon the story. Once I had that in place, other elements of the writing started coming together.

So why Somoza? Did you have a particular interest in the Nicaraguan revolution?

The story came from a couple of places. To start, it came out of an exercise at Bread Loaf, in a class taught by Reginald McKnight about telling lies convincingly, which I decided to do through historicality. I did a three-page scene about G. Gordon Liddy.

I have a Liddy story too!

Really? Yeah, he’s a fascinating character to take on. So I had him meeting Somoza, and then over the years the story shifted focus solely to Somoza. Also, my family is from Nicaragua, and I thought it would be interesting to engage with something from my political and cultural past, and really put the screws to this guy, really run him down because he really was a bad guy, and I had a lot of fun just “writing” him.

The agreed history is just one story, right?

Yeah. I mean, E.L. Doctorow says that history is a story, between the historian and his facts. So in writing a story based on historical figure, it’s interesting, the line between when you stick to the facts and render it with a certain verisimilitude and when you veer away.

Writers such as Jim Shepard have gone a long way in getting people to de-snobify about this false difference, or at least acknowledge the much more porous relationship between fiction and history.

Writers such as Jim Shepard have gone a long way in getting people to de-snobify about this false difference, or at least acknowledge the much more porous relationship between fiction and history.

Absolutely, and of course, nobody ever nails him for anything because he does his research, and [from a storytelling angle] his work is so imbued with the specificity and personal experience of the characters, who more often than not are on the periphery of historical events–which is a very smart approach.

Let’s talk about “Shakers,” which I thought was a really subtle use of the earthquake described in the story as a metaphor for “shakings,” be they personal or geological.

Yeah! [Laughs.] You know, an earthquake that huge would never happen, so it immediately becomes a metaphorical thing. It was a way of bringing all these individual and solitary lives together. So though you have these separate stories of individuals in solitude, you have them all gathered in one place, reacting to this one event, and touching on what we talked about before, that structural component was what drew me to whether I could write it or not.

Was the story ever longer? I ask because it reads like you had ten characters, and you closed your eyes and pointed at four and worked with them. Like there could have been six other people that you could have equally expanded upon and connected.

That’s great to hear that it reads like it could have gone on and on, because I’m not one of those writers who sits down and writes seventy pages and then gets it down to twenty. Me, I write two pages and get it up to twenty, and that’s how “Shakers” went, though I wrote it in five weeks, which is the fastest I’ve ever written a story.

That’s interesting, because it reads like it took a extraordinary effort of discipline to bring it down to the length it is—it could have been a novella.

I did want it to read that way, fluid in a sense, like it could have gone anywhere. I probably had one or two narrative lines that I cut out, but yes, there was something unusual about the writing of “Shakers,” organic and intuitive, different than any other story I’d written. It felt like a gift.

Which is nice, because they usually feel more like births. [Both laugh.] Another thing about the story I loved was that it felt, through this confluence of the personal and natural, like you were telling a geographic history of California, an accounting of the really different landscapes that make up California. It reminded me of that Pavement song off Crooked Rain, “Unfair,” which takes on this same confluence.

Cool! They must have read John McPhee.

Doubtless. And both the song and your story end up being celebrations of California.

Yeah, I mean one of the reasons I enjoyed writing “Shakers” so much was in rendering these landscapes. I’ve lived in Idaho for eight years and I miss California – its vastness – and so in the story I really wanted to revel in that vastness.

It reads like a love letter.

It is, very much so. And what better way to write a love letter to California than via an earthquake?

You couldn’t get much more integral to California than an earthquake. Even the ending, with the guy in the desert who’s probably going to die, [he] has this surge of love for the natural beauty around him as he wastes away with his broken leg. It’s weirdly funny, a demented commercial for the California tourist board, like, “California, right on!”

Yes! The ending is ironic but it’s also true. You know, I like combining the absurd and the profound, and I like that the story accomplishes that.

“Shakers” isn’t the only story that speaks to matters of place and geography. For example, “Only Connect,” which is so infused with the essence of Seattle, however abstract that sounds. Living here, I can tell you that you captured something on the page that encapsulates this temperate rain forest so well, and so mysteriously.

Yeah, and that story is the love letter to Washington.

Not surprising that it was published in Ecotone, considering the magazine’s focus on “place” in fiction, where setting is more the foundation of the story more than, say, character or humor or plot. “Only Connect” could only happen in Seattle and the surrounding areas it touches on, like Bellingham and Astoria.

It reminds me of what Flannery O’Connor said, which is that you can do whatever you want on the level of theme, but that the world of the story has to be real. You know, I tell my students that a story doesn’t work unless you ground it in a physical world that is concrete, that we can really imagine.

What are your thoughts on teaching?

You know, my goal on both the undergraduate and graduate level is not primarily to select the best writers and nurture them and bring them into the world. My goal is not to baptize the ones with the gift and tell the others, I’m sorry, my son, you must go to vocational school. That’s not the job. Ultimately teaching writing is the flip-side of teaching reading, by which I mean creating readers who are able to critically and thoughtfully respond to texts. On the undergraduate level especially, I try to dispel that, number one, your opinion about a story matters. No. I don’t care if you like it or not–how does it work? This is about learning craft. Number two, students think, well, I can write whatever I want. No, you can’t. The short story is a very demanding, exacting form – once you understand what went into crafting that story, then you understand where your response comes from, and that makes you a smart reader.

That echoes what Robert Coover said, that his job as a writing teacher is to make better readers.

That echoes what Robert Coover said, that his job as a writing teacher is to make better readers.

And if better writers are the result, that’s great too. Of course, that’s particular to the graduate level, where you’re aiming to find people capable of mastering the craft. On the graduate level, it can be very gratifying because the level of discussion and engagement is deeper.

More specifically, what about the arguments for and against MFAs?

I guess my rather benign defense of MFA programs in response to that question stems from my . . . um, irritation with writing programs being singled out as needing defending. So: Can you really teach writing? Well, it depends on whom you’re teaching it to. You can’t teach writing to anybody, but you can—just as in the teaching of medicine or engineering—teach it to somebody who has the drive to learn it and the knack to get better at it. The difference is that if you don’t show evidence of the drive and the knack, you get drummed out of medicine and engineering. We in writing aren’t quick to do that, because writing isn’t just a thing you learn, it’s a thing you do. It takes two or three years to get an MFA, and within that time the drive and the knack may be either fully present or they may be submerged, hidden, yet to surface. I’m not going to shut somebody down just because they’re not at the top of their game. (If somebody did that to me years ago, I wouldn’t be a writer, and you wouldn’t be interviewing me.)

I’m not saying that everybody who gets an MFA eventually becomes a writer; most don’t. But laying the groundwork in craft and technique, mentoring everybody—rather than separating wheat from chaff—can certainly help the ones who stick with it. To paraphrase the character Joe Gideon in Bob Fosse’s great allegory of writing programs, All That Jazz: I may not make you a good dancer, but I can make you a better dancer.

People like to have a strong opinion on MFAs in one direction or the other. With the haters, I often feel like, Really? People trying to become better humans in this tiny, unrenumerative way? That upsets you?

There are worse things to do than graduate someone with an MFA and send a bad writer out into the world. You know, you send out a bad engineer or a bad doctor and then you’ve got problems.

That’s why you don’t get an MFA in being a doctor. Really, MFA stands for Victimless Crime. [Both laugh.]

If I have a truly gifted undergrad, I will mention the MFA to them as something they might consider. But for other students who want to keep writing, I’m reminded of what a teacher told me, which is “Find your metaphor.” You know, find something else you’re good at to do while you write.

So you’ve got the collection out in the stores—unless you’re superstitious about talking about works in progress, would you mind talking about what you are working on now?

I won’t go into too much detail, but I am working on a novel, and am soon going out to UCross in Sheridan, Wyoming, where I’ll spend four weeks there focusing on it.

Sweet Sheridan. I was in a pretty epic snowstorm there once.

That’s why I’m going in August. [Laughs.] I’ve been working on it for about five years, then had to leave it for six months or so while we were getting the collection out, but now I’m full-bore on it, with due date looming. I started it grudgingly, out of necessity, but I have enjoyed figuring out the structure of the long form.

Jesus, novels are tough to write, huh?

They really are.

It’s like, musicians call it “running on blues power.” It’s just such an act of faith and love and inspiration, but you’re not sure if you’re actually running on, you know, quality [both laugh]. Considering that before this project you’ve always written short stories, has writing a novel made you appreciate them equally? Do you have a preference?

At this point I do prefer short stories to novels, both writing them and reading them. Not to take away from the novel, but like I said, the short story is a very precise, exacting form that’s also very artificial. I think the novel is more organic—it’s longer and baggier—and so for me it’s much harder to write a novel. I have had a hard time being engaged with it for five years, sustaining this interest, but I’m genuinely excited about this novel and eager to get back to work on it.

Further Links & Resources

Daniel Orozco / image from the University of Idaho's website

- Read J.T. Bushnell’s review of Orozco’s debut collection. In it, he writes: “Orientation is, without question and without hyperbole, one of the best books I’ve ever read. I can’t find words emphatic enough that aren’t already printed on its dust jacket, but I can assure you that all the words there are true.”

- You can also check out our most current features on other debut collections right here.

- Or check out some of our favorites from Story Month.

- For more on this author’s work, visit Professor Orozco’s University of Idaho page.

- Read some vintage Orozco: his story “I Run Every Day” published a decade ago in the fall 2001 issue of Zoetrope (Vol 5, No 3).

- I’ll take some Chemical Brothers and a side of zither with that, thanks: Largehearted Boy features Orozco’s sonic selections for his stories in their fabulous Book Notes series.

- And be sure to pick up a copy of Orientation: And Other Stories at your local indie bookstore.