This is my first book review. I held off longer than I meant to, reading advance review copies and looking for something it felt truly necessary to respond to. I’ve liked a lot of things, but you could say I wanted my first time to be special. It’s not that I don’t want to criticize ever. But for my first time, I wanted a book so good that angels applauded when I turned the pages, that I felt willing to risk hyperbole and embarrassment in declaring my love for it. When I read “Caught Up,” the first story in Jamie Quatro’s debut collection, I Want to Show You More (Grove Press), I knew this was the one.

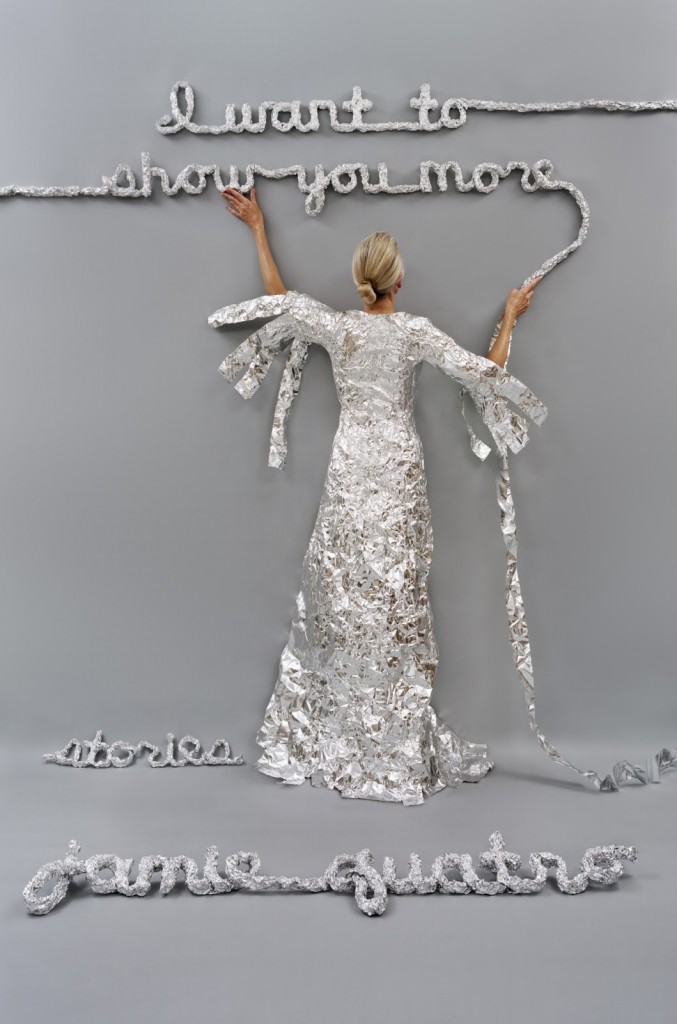

Then, on the day of its March publication, this book began to streak across the print landscape like the tin-foil comets that erupt from the elbows of the woman on the collection’s cover. In just over a month, I Want to Show You More has been adored in a dozen major publications. J. Robert Lennon called the stories “obsessive” and “dogged, brutally thoughtful” in the New York Times. In the New Yorker, James Wood described them as “savagely intense” and “remarkable for their brave dualism. He likened Quatro to a modern Flannery O’Connor. In Book Riot, Rebecca Joines Schinsky wrote, “it’s so good, I kind of want to lick it.”

Then, on the day of its March publication, this book began to streak across the print landscape like the tin-foil comets that erupt from the elbows of the woman on the collection’s cover. In just over a month, I Want to Show You More has been adored in a dozen major publications. J. Robert Lennon called the stories “obsessive” and “dogged, brutally thoughtful” in the New York Times. In the New Yorker, James Wood described them as “savagely intense” and “remarkable for their brave dualism. He likened Quatro to a modern Flannery O’Connor. In Book Riot, Rebecca Joines Schinsky wrote, “it’s so good, I kind of want to lick it.”

Me too, but my review wasn’t scheduled to run for another two months—we’d slated the book for May as part of our Short Story Month celebrations. Christ, what more could I say? If everyone agrees that it should be read, a book is past review. Jamie Quatro’s debut, a tightly-braided story collection about the body, the soul, and what they want from each other, has found its first audience. Now it awaits our second reading.

So I got out my post-its and colored pens. I flipped back and forth, looking for secrets and clues. I considered it the way we consider books worthy of rereading. Now I can add this to the chorus of voices: read it deeply. Live with it. Lie down with Quatro’s characters, alternately fed and starved by their unrequited lust and unrequited spirituality, and try to shake awake from their dreams. I Want to Show You More’s skinny spine carries us beyond our expected endpoints: there is life and death, but also decomposition. We watch children’s waxing and waning belief in the powers of their parents, and also the grown-ups’—ha!—yearning belief in something or someone who’ll parent them. We see the constant negotiation between desires of the body—to cause pleasure, to bask vainly in the eyes of the pleasured—and the body’s limits, from a marathoner’s weakening knees to a husband’s pain-killer addiction, from posing just-so for nude cell-phone photos to cancer, mortality.

Most of Quatro’s astounded new readers are agog over the same linked septet: the adultery stories. While the whole collection is thematically tight-knit, these stories in particular reward a reader’s deep attention. Quatro’s recurring heroine, the married mother of four in love with the Other Man, asks God again and again to clarify his requirements. She struggles to reconcile what feels necessary and right in her full-blooded life with a faith that seems to condemn it. What feels different here is the line Quatro draws between private, interior faith (her certainty that someone is up there watching) and religion, or how other people interpret God for her. But over the course of these stories, a conviction emerges: faith and lust are not unalike. They share irrational belief and desire, the pain and patience required to withstand want that cannot be satisfied, and, of course, the reliable aortic pulse of guilt.

In “Decomposition: A Primer for Promiscuous Housewives,” a corpse occupies a couple’s bed. To the husband, the corpse is bulky, inescapable evidence of the wife’s infidelity. To the wife, the corpse is a reckoning—sin come home to roost—but not as much as it remains he, the body of the man she loved. She sees that the corpse is disgusting, but she cannot believe it, not when it is his corpse.

I checked the body out, your husband says. It’s fucking wax.

He sits up.

You didn’t think it was real, did you?

It is a body, a man, the hidden affair, and the wife’s love for the man in the bed. The corpse is a manifestation of the wife’s desire and of her guilt, and of the husband’s need to shame her. “I need you to see that it won’t decompose,” he says. And the corpse, this fabulist element, neither wax nor human, is both the bodily material of another world and an otherworldly body. Her lust for the man persists, even after she logrolls him in a blanket and stores him in the basement. At the story’s end, the dead man, from inside his blanket, calls the wife a whore. “Don’t worry,” she assures him, “I won’t remember you this way.” She still believes in him. What is lust but blinding faith, even in the face of incontrovertible proof that it, whatever it is, is not what you thought?

Quatro’s stories are often fabulist, if fabulism is magical realism plus a reckoning. Magical realism seduces readers with dazzling elements dropped into shuffling, human lives. Fabulism makes us pay for them. A woman begs God to stop her or bless her, or even to help her desire her husband. “Want him,” she thinks, like an invocation. Later, in “Imperfections,” she and the Other Man show each other pictures of their real lives: birthday parties, children, summer vacations with their families. “What we were saying without saying it: here’s why this can’t happen.” These “realistic” stories mingle with the fabulist ones, casting shadows over both. In reading these stories that struggle with faith and lust both with and without “magical” elements, we begin to wonder if our lives aren’t more magical than we realize. How “realistic” is reality anyway, what with medical curses, ghostly depressions, and visitations by lusty spirits? The woman chats with her lover on the phone in the grocery about Honeycrisp apples and feels a kind of ascension when he says that he loves the Honeycrisp, too. Crazy in love: it’s either magic or it feels like it is, and there’s no point in differentiating.

“Caught up” has the Other Man fantasizing about the physical realization of their lust: “It would be devotional, he’d said. I would lay myself on your tongue like a communion wafer.” It’s an image that bears repeating: later, in the Christian orgy-cult fantasy “Demolition,” a young parishioner “enacts God’s Mystery” for the first time. “Body of Christ, broken for you, he said, placing himself on her outstretched tongue.” In repurposing this comically “devotional” sexuality from a realistic, intimate story in a surreal, conceptual one, Quatro suggests that lust is a cult of two.

“Caught up” has the Other Man fantasizing about the physical realization of their lust: “It would be devotional, he’d said. I would lay myself on your tongue like a communion wafer.” It’s an image that bears repeating: later, in the Christian orgy-cult fantasy “Demolition,” a young parishioner “enacts God’s Mystery” for the first time. “Body of Christ, broken for you, he said, placing himself on her outstretched tongue.” In repurposing this comically “devotional” sexuality from a realistic, intimate story in a surreal, conceptual one, Quatro suggests that lust is a cult of two.

In all this blurring of reality, grief, and sex, there is a happy debt of influence to Gabriel Garcia Marquez. I can transport the brothel where Aurelianio Babilonia gleefully balanced a beer on his penis right to the base of Quatro’s Lookout Mountain. Perhaps Babilonia’s heir here is the Other Man in the story “You Look Like Jesus,” sending naked selfies where he reclines in his office chair, “one arm flung out to the side.” There is, in longing, room for ecstatic humor. Quatro pinpoints the humdrum silliness in our lust and our shame, the animal instinct lurking—or racing past—the supposedly governing spiritual principles.

But instead of the Buendía family’s hauntings by ghosts, Quatro’s heroine is haunted by faith and by her conflicts within Christianity. In “Caught Up,” she experiences a series of visions, indistinct but overpowering, as a child:

When I told my mother, she said, God speaks to his children in dreams. She said we should always be ready for the Lord’s return: lead a clean life and stay busy with our work, keeping an eye skyward. I pictured my mother up on our roof, sitting in a folding chair, snapping beans.

Maybe her mother is preparing for the Lord’s return, but for the narrator, her mother is the Lord herself: it’s to her that she confesses, seeking absolution, and it is her judgment and forgiveness that serves as an earthly surrogate for the heavenly sort.

It’s this picture of the mother that the reader carries to the next page, when the narrator, grown and married and a mother herself, confesses to her mother that for almost a year she has been having a phone affair with another man. When the Other Man tries to persuade her that God is telling them yes, she laments, “I wish I knew God your way.” Her soul has placed an ad in the help-wanted section of the paper: who is the right person for this job, and what is this job, anyway? Is God a laughing Dionysus? Or is God your pinch-mouthed mother, sitting on the roof and making sure you don’t sneak out the bedroom window?

The mother-God wins, it seems, and years later, still suffering the absence of the Other Man, the narrator finds her faith unsettled again: “I told her that I wished for a literal second coming and consummated Kingdom because then the man and I could spend eternity just talking.” The mother then realizes her mistake: this affair was never consummated, not in that way. The narrator says:

I can’t believe all this time you’ve been thinking I went through with it.

You might as well have, she said. It’s all the same in God’s eyes.

Her mother’s words echo over the two hundred pages that follow, as we fall into the love affair ourselves: Oh, how profound the regret, then, that she didn’t.

Links & Resources

- For more on Quatro’s work, interviews with the author, or for information about appearances, please visit the author’s website.

- Read Quatro’s story “The Anointing” in Guernica.

- You can also read J. Robert Lennon’s Sunday Book Review of I Want to Show You More in the New York Times.

- And here’s James Woods in the New Yorker on Quatro’s collection, as well.

- Finally, check out Rebecca Joines Schinsky’s recent Fresh Ink recommendations for Book Riot.