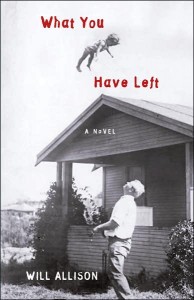

There are ways in which novels with disjointed narratives please and ways in which they frustrate. Will Allison, in his first novel, What You Have Left, works hard to eliminate the general confusion that can result from a fragmented structure. His steady pacing, control of tone, and knack for detail and humor all conspire to make the shifting landscapes and time periods of What You Have Left feel natural and purposeful. This encourages the reader to lean into the narrator(s) even further—which of course frees Allison to show us more of his tricks. The structure also seems like an appropriate mirror for the subject of What You Have Left: the Greers, a family torn apart and alternately struggling and refusing to reconstruct itself.

There are ways in which novels with disjointed narratives please and ways in which they frustrate. Will Allison, in his first novel, What You Have Left, works hard to eliminate the general confusion that can result from a fragmented structure. His steady pacing, control of tone, and knack for detail and humor all conspire to make the shifting landscapes and time periods of What You Have Left feel natural and purposeful. This encourages the reader to lean into the narrator(s) even further—which of course frees Allison to show us more of his tricks. The structure also seems like an appropriate mirror for the subject of What You Have Left: the Greers, a family torn apart and alternately struggling and refusing to reconstruct itself.

The novel begins and ends with Holly, abandoned on her grandfather’s farm by her father, Wylie, the day of her mother’s funeral. We watch her age from 20 to 30, as she inherits the farm to which she was abandoned, marries the contractor her grandfather hired to renovate the house, and has a child of her own. Infusing every event of her later life is the damage wrought on her by her mother’s sudden death and her father’s disappearance. We see Holly driving around intoxicated, addicted to video poker, ignoring her husband, refusing to quit smoking. We watch her passion to search for and connect with her father slowly fading. Failing to find Wylie in the physical world, she begins to look for him—or someone else to blame for her loneliness—in her marriage and in herself.

We also get Wylie’s perspective and that of Holly’s husband, Lyle; the book cycles through all three points of view, jumping from decade to decade, alternating between first- and third-person. We see all three characters struggle to understand their worlds while making due with too few resources or options, with not enough confidence or support or self-control. We feel empathy and anger towards all of the characters at different times in the story, but the back-and-forth never draws our focus away from the story.

Allison keeps the drama high, playing a game of pass-the-baton where the resolution of each chapter leads directly into the conflicts of the next one. This may seem like a simple proposition—isn’t that what every novel does?—until we factor in the time, scene, and character shifts. Each chapter presents us with new circumstances—births and deaths, addictions and infidelities—but these situations feel constructed out of the emotional rubble of the previous chapter’s demolition. Holly’s reluctance at inheriting her grandfather’s land mentally prepares us to step into Wylie’s awkwardness as a young father. Lyle’s growing awareness of his wife’s disinterest sets the stage for our encounter with Wylie, 22 years earlier, battered from rootlessness and alcoholism, trying to make sense of the life he’s made, the self-exile he’s chosen. Allison writes his characters in all stages of life, as they struggle to get and keep love they fear they might not deserve, and he shows us, through the leaping perspectives, how legacies are accepted, denied, and subverted but rarely understood. Holly, Wylie, and Lyle can neither see where they are going nor comprehend sufficiently the forces that guide their actions. Likewise, the author capitalizes on the story’s emotional momentum to push the reader—as well as his characters—into new and often uncomfortable territory.

But Allison is not just showing off. He uses these sleights-of-hand to display moments that would otherwise go undocumented, and to possibly hint at how compassion begins: by acknowledging the nature of hidden suffering and the loneliness of self-doubt and uncertainty. Allison is such a master illusionist that we do not know what he is doing until he has already opened our eyes—and his is such a beautiful, empathetic voice that we forgive any legerdemain he may have used to trick us out of blindness.