In February of 2002, I drove north with my pregnant wife from our home in Maine to the distant coast of Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island. The journey took two days.

My wife’s family owned a small cottage in the village of Inverness, and the cottage hunkered on a hillside overlooking the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. Inverness was a desolate, frozen lunarscape that winter—the wind rushed in off the ocean day and night, Osprey hung in the ashen sky, and the air was thick with salt. The sky and the sea merged into a single cold, gray wall erasing the horizon line, and we stayed inside with wood in the woodstove and hot soup on the kitchen stove. We were, I felt, in a place out beyond what we knew.

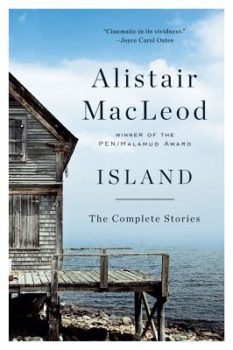

I sat in the Cape Breton cottage and read for the first time the Canadian author Alistair MacLeod’s short stories. I had stumbled upon his collection Island: The Complete Stories (2000) there in Inverness, where MacLeod’s family settled in 1946, and where he still spends his summers. There was no way of knowing as I read MacLeod’s hypnotic stories that my wife would give birth in September to a perfect baby girl, that an insurmountable chasm would grow between us, and that we would be divorced in just three years time. All I knew was how MacLeod’s stories filled and warmed my chest during that bitter Cape Breton February.

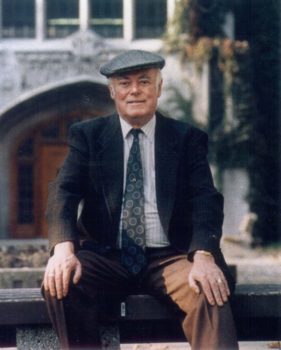

MacLeod is something of a national treasure to his fellow countrymen, yet here in America the septuagenarian remains largely unknown. His relative obscurity in this country may be due in part to the fact that prior to publishing his debut novel in 1999, the sweeping, multigenerational, Scotland-to-Nova Scotia epic No Great Mischief, MacLeod had exclusively published short stories since the late 1960s.

MacLeod is something of a national treasure to his fellow countrymen, yet here in America the septuagenarian remains largely unknown. His relative obscurity in this country may be due in part to the fact that prior to publishing his debut novel in 1999, the sweeping, multigenerational, Scotland-to-Nova Scotia epic No Great Mischief, MacLeod had exclusively published short stories since the late 1960s.

MacLeod’s fictional obsession is life in Canada’s easternmost province of Nova Scotia in general, and the outlying Cape Breton Island in particular. His quiet, deceptively simple portraits of the working-class people are rich and precise. MacLeod is at the peak of his powers when writing within his deepest sympathies: family, fishing, coal mining, logging, manhood, desire, and regret. “The Boat,” the very first MacLeod story I ever read, manages to contain the majority of this list.

Island gathers together MacLeod’s first two story collections—The Lost Salt Gift of Blood (1976) and As Birds Bring Forth the Sun and Other Stories (1986)—plus just two new stories. The only thing MacLeod has published since 1999’s No Great Mischief and 2000’s Island is an illustrated edition of To Everything There Is a Season: A Cape Breton Christmas Story (2004), a story he originally published in 1977 in Canada’s Globe and Mail, and then collected in As Birds Bring Forth the Sun and Other Stories.

I mention all these dates and facts about MacLeod’s publishing history to emphasize just how small and precious this exceptional author’s cannon really is: sixteen stories. If we consider MacLeod’s sixteen stories spread across the forty-five years since his first story publication in 1968, that’s roughly one story every three years.

“I write them very carefully,” MacLeod once told an interviewer from Canada’s National Post. “I don’t do drafts, I change them sentence by sentence. You have to be very certain what you’re doing. I write the conclusion partway through. It keeps me focused—I think about what I want to say.”

Several MacLeod stories compete in my heart for the title of favorite. The list would surely include “The Lost Salt Gift of Blood” and “The Road to Rankin’s Point,” but his masterpiece might be that very first story of his that I read: “The Boat.” First published in the Massachusetts’s Review in 1968, and then collected in the 1969 edition of the Best American Short Stories, “The Boat” opens with a stunning example of MacLeod’s gift for balancing language between the lyrical and the declarative with utter authority:

There are times even now, when I wake at four o’clock in the morning with the terrible fear that I have overslept; when I imagine that my father is waiting for me in the room below the darkened stairs or that the shorebound men are tossing pebbles against my window while blowing their hands and stomping their feet impatiently on the frozen steadfast earth. There are times when I am half out of bed and fumbling for socks and mumbling for words before I realize that I am foolishly alone, that no one waits at the base of the stairs and no boat rides restlessly in the waters by the pier.

The short story master Alice Munro once wrote, “It is hard to think of anyone else who can cast a spell the way Alistair MacLeod can.” Reading the opening lines of “The Boat,” it is hard to argue with Munro’s assessment of her fellow Canadian.

“The Boat” is relatively simple: an older man reflects on his Cape Breton youth, his parents, and the family fishing boat. “I first became conscious of the boat in the same way and at almost the same time that I became aware of the people it supported,” the narrator recalls early in the story. In MacLeod’s hands, the narrative weaves confidently between youthful observations and the reflections of a more mature man.

Two powerful poles set the stakes around which this story revolves: the narrator’s strong, beautiful, stoic mother (“My mother was of the sea, as were all of her people, and her horizons were the very literal ones she scanned with her dark and fearless eyes”) and his older, hardworking, quiet father (“When he was not in the boat, my father spent most of his time lying on the bed in his socks, the top two buttons of his trousers undone… The pillows propped up the whiteness of his head and the goose-necked lamp illuminated the pages in his hands”).

Near the end of “The Boat,” the narrator recalls how in the months before he struck out from his tiny Cape Breton village to make a new life for himself in Canada’s cities, he fished many long, hard days alongside his father:

And I stood at the tiller now, on these homeward lunges, stood in the place and in the manner of my uncle, turning to look at my father and to shout over the roar of the engine and slop of the sea to where he stood in the stern, drenched and dripping with the snow and the salt and the spray and his bushy eyebrows caked in ice.

Father. Son. Boat. Resentment. Regret. Intimacy. MacLeod’s characters are alive to us in both their confusion and their fog-lifting realizations—the acceptance that we all must grapple with how we remember our parents in our youth versus how we see them as adults. Slow and rich and so atmospheric that you can taste the ocean’s salt spray on your lips, “The Boat” is run through with that rarest of qualities in fiction: the story feels mythic. The exceptionally astute Irish author Colm Tóibín has noted, “The genius of MacLeod’s stories is to render his fictional world as timeless.”

This past summer, the little girl who was growing in my ex-wife’s belly when I first read Alistair MacLeod’s stories turned ten.

Just weeks before her birthday, my daughter and I took an afternoon swim in the Saco River. She was suddenly strong enough to swim alongside me far out in the wide river’s gentle current, suddenly strong enough to imagine, like me, that we might even one day swim all the way across to the further tree-lined shore if only we could take our time and rest along the way, stop to drift on our backs in a dead man’s float and stare up at the impossibly cerulean sky—in an unspoken pact, we believed we were capable of moving out beyond what we knew.

Just weeks before her birthday, my daughter and I took an afternoon swim in the Saco River. She was suddenly strong enough to swim alongside me far out in the wide river’s gentle current, suddenly strong enough to imagine, like me, that we might even one day swim all the way across to the further tree-lined shore if only we could take our time and rest along the way, stop to drift on our backs in a dead man’s float and stare up at the impossibly cerulean sky—in an unspoken pact, we believed we were capable of moving out beyond what we knew.

Later, my daughter and I sat on the shore on our towels, the August sun fading, our bellies full with picnic sandwiches. And because she asked me to, I read aloud to her “The Boat.” When I finished and set the book aside, my daughter—her long dirty-blond hair wet and clinging to tan cheeks—looked at me and said quietly: “Whoa…”

To read Alistair MacLeod is not simply to glimpse the land, language, and hopes of his roughhewn Nova Scotians, it is to discover the hearts of our fellow humans—and to discover ourselves there, suddenly illuminated in the cold shock of salt spray.

Further Links and Resources:

- Alistair MacLeod discusses the art of writing slow.

- Alistair MacLeod reads from “The Boat” at the 11th International Conference for Short Story in English (Note: Audio is so-so).

- Alistair MacLeod and the Cape Breton thing (National Post).