I’m not the kind of bibliophile who owns multiple copies of the same book—first editions, paperbacks, reprints, limited editions, and so on. I’ve never really had the living space to accommodate such a habit, but more over my books are littered with margin notes, end notes, notes for stories I’m working on, notes for stories I want to work on, so many red and blue-inked annotations that purchasing a new copy of Salinger’s Nine Stories or Dybek’s The Coast of Chicago would feel like cheating on the marked-up copies, betraying some long-term, intimate relationship.

I’m not the kind of bibliophile who owns multiple copies of the same book—first editions, paperbacks, reprints, limited editions, and so on. I’ve never really had the living space to accommodate such a habit, but more over my books are littered with margin notes, end notes, notes for stories I’m working on, notes for stories I want to work on, so many red and blue-inked annotations that purchasing a new copy of Salinger’s Nine Stories or Dybek’s The Coast of Chicago would feel like cheating on the marked-up copies, betraying some long-term, intimate relationship.

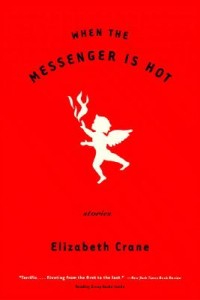

So there was no reason to purchase a hardcover edition of Elizabeth Crane’s debut collection When the Messenger is Hot a few weeks ago at a used book sale. I own the paperback version, have lived with it, have scribbled my way through the stories time and time again since I first picked it up as a sophomore creative writing major in college. But as I plucked the yellowing-covered volume from a row of crime novels and began to leaf through it, I was struck with the same kind of awe at the collection’s opening story as I was when I first encountered it all those years ago.

“The Archetypes Girlfriend” is a breathless, hurried story. Rendered in second person, it chronicles the love life of an unnamed narrator through the catalog of various women he’s dated. As the story progresses, we see the life of our narrator unfold via the types of women he chases after. Relationships blur and become an oddly singular experience in the narrator’s mind. We learn through the precise, slicing way in which he describes (and defines) these women the kind of relationships he gravitates toward (tumultuous, maybe obsessive) and the kind of life he’s seeking.

You love her because she can talk about cars or dogs or wild game or politics, about which she has a point of view that you may or may not agree with, and because she never asks what you’re feeling, for which she is exalted until you realize that this is because she isn’t about to tell you either.

The story is stuffed with digressions. Insights incased in parenthesis. Asides trapped between emdashes. It’s a voice-driven fiction, often comical, and so goddamn truthful that at times you transcend seeing yourself in the fiction and begin seeing the fiction in yourself. And sure, these and the story’s many other attributes (pacing, structure, an intentional avoidance of the futile task of trying to describe places or settings) were wonderful things to rediscover, but what hit me hardest was the adrenaline-slapped feeling that, in fiction, anything is possible. It was the same heart-in-the-throat feeling I had when I read the opening passage as an undergrad, so sure of what a short story was: third person narration, high-flown language, everyone is unhappy, everyone is alone, so much pain, bird imagery, clouds, a late-game epiphany.

Jesus, what a sad conception. And I thank Crane’s opening passage for pulling the wool from my eyes to the limitlessness of a great short story:

Sarah or Anya or Max is five foot ten, five foot nine or five foot eight, but never shorter, and she’s naturally thin. She’s thirty or she’s twenty, or she’s almost forty and looks ten years younger even when she rolls out of bed in the morning. She’s not a flawless beauty, but you think she is, and she has perfect skin and wears no makeup, or she won’t leave the house without eyebrow pencil and blood-red lipstick, her trademark.

Time has passed. I’ve got gotten older, finished college, completed my MFA, gotten married, moved around the Midwest, worked a 9-5 office job, watched my student loan debt flicker and shrink like the flame on a trick candle. And while I’ve certainly grown as a fiction writer, this story still impresses upon me the importance of being open-minded with your own work: of not being afraid to question your aesthetics, your voice, your style, your ideas about what your fiction can look like, sound like, feel like. In many ways, the more we write and read and complete MFA theses and publish work, the threat of becoming cross-armed and entrenched in certainty about how to define the short story form grows.

This is dangerous thinking. This is confusing the difference between understanding the tools needed to build a satisfying, poignant piece of art and always relying on the same tool no matter the job. This is where the value of Crane’s story nests. All these years later “The Archetypes Girlfriend” still excites me, still makes me wonder, still breathes possibility.

Oh, and in case you’re wondering, I did buy the book sale edition of Crane’s book, and I’ve been carrying it around in my backpack ever since, revelling in the knowledge that it’s nearby. So maybe there is something to owning multiple copies of the same title, and maybe there’s something I can learn from it.

Further Links and Resources:

- Visit Elizabeth Crane online.