- Jesse Ball’s fourth novel, Silence Once Begun (Pantheon), is the hunt for the story of a Japanese man named Oda Sotatsu who signed a confession for a crime he did not commit, ceased to speak, and was given to the gallows. It is a ball of old and forgotten thread, remnant odds and ends that Ball has knotted together with deceptive casualness. You pull on the strands of the prison interrogations, yank at the frayed end of a letter from Sotatsu to his family, undo the knot of the press coverage of the trial, and tug and tug at the clumped interviews conducted with Sato Kakuzo, the man who convinced Sotatsu to sign the confession, and Jita Joo, Kakuzo’s partner with whom Sotatsu may or may not have fallen in love, but still there is more thread. You unwind and unwind and unwind, hoping to reach the middle of the ball and find some answers to the mystery of why Sotatsu signed the confession and some resolution to the pained results, but when you reach the center there is of course nothing but the end of the thread and then open air.

Conveyed as a kind of oral history by a narrator named “Jesse Ball” but published as fiction, Silence Once Begun constantly teases you with the impossibility of knowing what is true and what is not, what was truly discovered via research and interviews and what was created whole cloth. Even Ball’s motivation is uncertain: he tells us Sotatsu’s story interested him largely because his wife and partner had recently gone voluntarily mute and left him, but is this one of the truths or one of the lies? And if every single thread of the novel is fabricated, then why and how does it hurt so much to read? You could send out Google query after query, but you’d never find all the answers, and it’s the mystery and then accompanying sense of unease and wonder that keeps the pages turning. Maybe the questions are part of the point anyway. Maybe it’s like someone in Ball’s earlier novel The Curfew says in regards to an epitaph: “It doesn’t matter what the truth of it was, does it? It’s just to have people stop and be quiet for a moment.”

Ball’s writing has always made me stop and be quiet, ever since his first published novel, Samedi the Deafness. There is a mollifying effect to his stories, each one, that makes me want to sit with them until done, to read them in as uninterrupted a manner as possible within the timeframe of my days. I read them in one or two night swallows, letting his stark, plain-spun prose glide down my eyes like smooth water, as quickly read as Ball claims they are written, as you’ll see. Like with many books, I’ve forgotten most of the plot of Samedi the Deafness, The Way Through Doors, and The Curfew, but their effect and images linger. If you’re anything like me, you’ll read Silence Once Begun once, quickly, to answer as many of your questions about the life of Oda Sotatsu as possible, and then once more, slowly, to linger on how it affected all those around him.

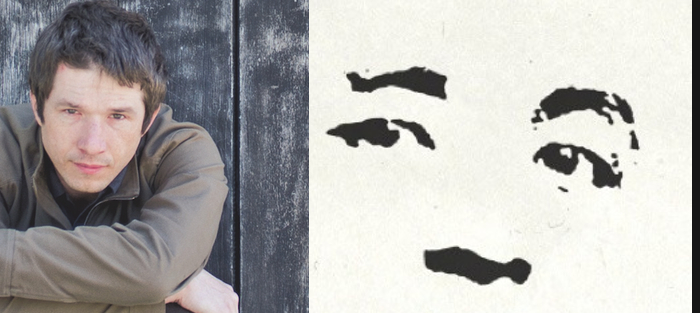

Recently Ball, the author of a book of poetry as well as his novels and stories and the teacher of courses on lying and lucid dreaming at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s MFA in Writing, took time out of his lying and dreaming and teaching to answer some questions of mine via e-mail. In keeping with his curriculum, I asked him to lie to me during one of his responses. It could be either a big lie or a small one, but he could not tell us which answer it rested in.

Consider this a game of sixteen truths and a lie.

Interview:

Shawn Andrew Mitchell: At one point in Silence Once Begun, the narrator proposes a catalog of the human qualities of buildings and alleys, describing a “quality of firmness or importance, secret importance, that one puts on small geographies and features of landscape, houses, yards, hidden spots between trees.” To give the reader a sense of setting, could you describe for us the human qualities of the place you are now?

Jesse Ball: My house shambles along like an old pensioner returning from his supper down an empty street. The buttons of his coat are done up wrong. One of his shoes is patched. He is carrying a walking stick, which he feels makes him a sort of gentleman.

One of your earlier two novels, I can’t check which one because I don’t have them with me here in Korea, included a note that the names in it were borrowed from the gravestones in a particular cemetery. William in The Curfew was a writer of gravestone epitaphs as well, and it might be noted that though the narrator never visits the grave of Oda Sotatsu in Silence Once Begun, he does attempt to visit the place of his imprisonment and execution. What draws you to cemeteries and places of death? What human geographies lie there?

Well, I have said elsewhere if I will call myself something, if I must, then, some people are doctors, lawyers, shopkeeps, boilermakers, athletes, playwrights, filmmakers, politicos, and I would humbly advance that I am a cemetrist. I am happiest in cemeteries, though not for any dark or dramatic reasons. There’s nothing Gothic about it. Rather—the absence of people, the space, the calm, the quiet persistent upswell of the reminder: pause a moment in your life. Look out your eyes. I spent a lot of time in cemeteries as a child, because a large one was away behind the house I lived, through a wood full of hollies and bramble patches. I believe there are houses there now, but the graveyard remains.

The puppeteer Mr. Gibbons in The Curfew tells his young pupil that “the effect of irrational beliefs on your art is invaluable. You must shepherd and protect them.” What are your irrational beliefs when it comes to writing?

I can only write if I have stolen something valuable that day. I can return it later if I like. A question for you: Is this the lie you asked me to tell?

Elsewhere you have described writing as a performance, and I get a sense of that in your work, a sense of improvisation. There is a plot or structure that is moving forward, more or less lockstep, but there is also a looseness, an openness from which a well-polished tangential detail or line of dialogue can emerge that implies a great deal about the rest of the story. When I read that quote of yours, I romanticized your writing process as the opposite of mine, which is messy and slow and often interrupted. I picture you in a clean, stark room, with one desk and one chair and plenty of natural light, possibly one window without a particularly beautiful view. There’s maybe one plant, and only a notebook and a pen. When you emerge again a month or three later, you have a novel and a resplendent beard and are babbling in the tongues of your characters. I know this is probably facile and ridiculous. What is your writing routine really like? How might it be considered a performance?

When I do write, which is seldom, I often do so in public places—but if it is somewhere English is spoken, I must have earplugs. I will write on a device with a keyboard for speed, but also sometimes on paper. I sometimes draw things while thinking. Mostly, though, the thinking takes place while writing. The books aren’t premeditated. They take place, as it were, beneath the pen. Usually, the period of writing is anywhere from 4-14 days.

Is there a long editing process after that? I have to let something sit for a while, and then it takes me forever to edit. It’s sometimes fun but often only time-consuming and necessary. What is your editing process like?

I don’t edit—I think the original form is best. Sometimes Jenny will ask me for more—and then I will add a section, as happened with Silence Once Begun.

How long did Silence take? Was the process for this story any different than the others?

Not substantially. I wrote it towards the end of August, I believe, in 2011. Then, I added a section in spring of 2012. I imagine, then, it was a week in 2011 and a few days in 2012. The next one, A Cure For Suicide was about 6 days in Berlin. Then, in December I added a section, so that was another day.

Let’s talk more specifically about the performance of Silence Once Begun. In its stark style, its setting, and its subject matter, the novel reminded me of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s short story “In a Grove,” with its multiple and conflicting accounts of what happened in a clearing in the trees, how the body came to be on the ground. Did you read him or any other Japanese literature while you were working on this novel? If so, how did it feed into it?

Let’s talk more specifically about the performance of Silence Once Begun. In its stark style, its setting, and its subject matter, the novel reminded me of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s short story “In a Grove,” with its multiple and conflicting accounts of what happened in a clearing in the trees, how the body came to be on the ground. Did you read him or any other Japanese literature while you were working on this novel? If so, how did it feed into it?

I haven’t read, “In a Grove,” but certainly should do so. How embarrassing! Of course, I’ve seen Rashomon. In fact, when I was a projectionist, I screened it several times. Watching things from the projectionist’s booth is quite a pleasure. I don’t believe I read any Japanese literature while writing, Silence, but I certainly do read and adore it. The Japanese books I’ve been reading most recently are books on the game of Go. The writing is sometimes wonderful. Toshiro Kageyama, for instance, is quite a personable fellow (in his text, Lessons in the Fundamentals of Go).

I didn’t know you worked as a projectionist. What are some of your favorite movies to have screened, and why?

Well, as to the whys and wherefores of such matters… we must lack the space, I imagine. I screened silent films and those I loved most—Passion of Joan of Arc, especially. Another film I adored—it changed me completely to see it: Children of Paradise.

What other Japanese writers or artists do you like especially?

Kawabata. Basho. Iyama Yuta.

All of the details of Sotatsu’s story are surrounded by and laden with mystery, but when you pick up the objects, facts, and testimonies, you only find more questions. How did you maintain this sense of mystery throughout, for both yourself as a writer and us as readers? Was there ever a temptation to untangle all the riddles?

I try to be clear and honest. If one is clear and honest, and only that, mystery leads on to further mystery, bleakness to further bleakness, occasionally mitigated with slight pulses of joy or satisfaction. The world is not necessarily miserable, but it surely will be. We have only the light of our little candles. I could not untangle all the riddles and remain honest. The world is in actuality tangled & tangled, tangled, tangled.

When I reflect on this book, I want to tromp out capital letters. Situationism. Simulacra & Simulacrum. Existentialism. But when I was reading it I was only captured by the story. How do you balance narrative with philosophy? What is philosophy’s proper relation to fiction, at least to your fiction?

I try to just think in terms of books, or even, if I can, just in terms of thought, speech, et cetera. A good work is a moment of clear thought. Those works that we can give the full welcome of our mind to—they are few and far between. Nonetheless, of course, there are many of them, enough to last a whole life. I don’t believe, to answer your question, that there need be a choice to move towards philosophy or towards fiction.

Sotatsu’s father describes someone as having a liar’s respect for truth, which is too much respect. This novel plays with being nonfiction, in making the narrator “Jesse Ball” and in producing artifacts and realia, but we never know exactly what is true and what is false, where the line between fiction and nonfiction has been drawn. It’s part of the heady effect of the story. You teach a course on lying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s MFA in Writing program. How do you feel knowing how to lie well ties in with writing fiction, and how would you describe this book’s relation to the truth and to nonfiction?

I think, as I say above, there are some well-intentioned human works which can be used sturdily to navigate our difficulties. That they are “true” or mendacious, that they are fictional, non-fictional—I think it matters very little, provided that they accomplish their function.

What human works, books or otherwise, have served that function for you?

Bachelard—Poetics of Space, Winsor McCay—Little Nemo, Whitman—Leaves of Grass.

You also teach a course on lucid dreaming. There is a lot of imagery in your work that feels archetypically dreamlike. There are wells and holes and long staircases, and there’s also that moment when Jita Joo calls herself “a great trader like Marco Polo, who visits an interior land,” which sounds like a great description of lucid dreaming. How is lucid dreaming connected to your waking writing? And would you be willing to describe for us a recent dream you had?

You’re right—that does sound a bit like lucid dreaming. Of course, Marco Polo got some credit for his travels, though. Most dreamers can receive nothing but the delight which has already arrived and gone at the point of memory. What is that line from Shakespeare, “Dreamers often lie…” That’s Mercutio—to which Romeo says, “in bed asleep while they do dream things true.” But, even supposing that Romeo is right, it is often just the dreamer to whom the dream is useful. Of course, it needn’t be so. Paying attention to dreams can yield wonderful harvests. In some cases, men and women have dreamed of an invention or concept that proved to be the life’s chief contribution. The Committee of Sleep is a book about this.

A dream from last night. I was a young woman who was asked to dissect something—some kind of dog. I was, instead, dissecting a goat in the back of a restaurant. For an unknown reason, I had to flee. I was traveling along through the streets of a town, trying to find a safe place. Then, I was in a bed in a sanitarium. Everyone seemed very friendly. Many people had dogs on leashes. Here were people also on leashes. My movements were not constrained, although the nurses were constantly offering me food. I was next lurking by a fence at the edge of the property. I intended to escape, and was waiting for someone to go away, a person who stood nearby, in order to make good my plan. This person would not go away, and I didn’t want to turn to look at him (or her).

Going back to that puppeteer in The Curfew one more time, he tells the girl he is tutoring that “you will decide if you want the puppet show to be funny or not. The puppet show will always be sad, but it can be funny in parts.” Your stories are not often praised for humor or lightness, but there are brief interludes of humor and happiness, especially in these most recent books, such as when William and his daughter get to play a game of riddles, or when Sotatsu’s brother’s daughter tries to make off with the narrator’s hat. In the end though, I found Silence Once Begun very, very sad, especially on the second read since I was more focused on how the mystery affected the characters than on the mystery itself. Do you believe this line about puppet shows applies to fiction as well? Will it always be sad?

Going back to that puppeteer in The Curfew one more time, he tells the girl he is tutoring that “you will decide if you want the puppet show to be funny or not. The puppet show will always be sad, but it can be funny in parts.” Your stories are not often praised for humor or lightness, but there are brief interludes of humor and happiness, especially in these most recent books, such as when William and his daughter get to play a game of riddles, or when Sotatsu’s brother’s daughter tries to make off with the narrator’s hat. In the end though, I found Silence Once Begun very, very sad, especially on the second read since I was more focused on how the mystery affected the characters than on the mystery itself. Do you believe this line about puppet shows applies to fiction as well? Will it always be sad?

It will always be sad, for it must, if it is good, enable you to further pierce the world with your sight, and if you do, you will be further grieved. Of course, there are other things that join this dance. For instance, a life of grief can be joyful too. You are at least alive.

Finally, William’s former violin teacher in The Curfew describes playing the violin as an absence of things. “A sonata is not the passing of geese,” she says. “It is not a stream’s noise, not the sound of a nightingale. A violin does not speak, does not chatter. The catastrophe of a symphony’s wild end is not a storm breaking upon land. It is not the shuddering and sundering of a house. But it is in part, […] the understanding of these things.” To close out the interview, can you describe fiction as an absence of things? What is fiction not?

It is not itself the deepest water, but I think it can be a map to deep water.