1. The more obvious a term, the harder it is to define. For evidence, look no further than former Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart’s frustrated attempt to define pornography: “I’ll know it when I see it.”

2. I know story when I see it. I know narrative. But can I define it? Can anyone?

3. “Ultimately,” writes Jerome Stern in Making Shapely Fiction, “A…story is what feels like a…story.” Later he provides what he calls “the most pragmatic definition: a story is what the editor says is a story.” I like Stern’s book a lot, but here he’s basically saying I see your cop-out, Justice Stewart, and I raise you a pass-the-buck. We can do better. Or at least fail more audaciously.

3. “Ultimately,” writes Jerome Stern in Making Shapely Fiction, “A…story is what feels like a…story.” Later he provides what he calls “the most pragmatic definition: a story is what the editor says is a story.” I like Stern’s book a lot, but here he’s basically saying I see your cop-out, Justice Stewart, and I raise you a pass-the-buck. We can do better. Or at least fail more audaciously.

4. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “story” can mean “an incident, real or fictitious, related in conversation or in written discourse in order to amuse or interest.”

5. But does it need to be intended for entertainment (i.e., to amuse or interest)?

6. No

7. Down the page, the OED acknowledges that stories may serve other purposes. A story can be testimony or news, “an account or representation of a matter; a particular person’s representation of the facts in a case.”

8. A non-exhaustive list of purposes served by stories: to capture a moment, to explain things we don’t understand, to infect with values or beliefs, to lionize, to condemn, to get people to sleep with you, to get little people to sleep, to save your own life, etc.

9. According to lore, one famous writer said that the purpose of all storytelling is persuasive. “The undercurrent is always the same: it’s the storyteller saying, Love me, love me.”

10. Onto the other point in that initial definition: Does narrative always need to take oral or written form?

11. Also no.

12. Now that we’ve clouded the purpose and stripped away the form requirements, where does that leave us? With an incident? An incident is not a story. If all you have is an incident—So, uh, this weird thing happened at the store—what you have is an anecdote. Grits ain’t grocery, eggs ain’t poultry, and an anecdote ain’t a story.

13. You may have noticed that I’m using the terms “story” and “narrative” interchangeably. Also that I’m not drawing any distinctions between “true” stories and fictional tales. That’s on purpose. This definition-quest is hard enough without extra layers of difficulty.

14. To Aristotle, a story was a logically linked series of events. It had a structure that included a beginning, a middle, and an end, characters who remained the center of attention through the piece, and a resolution that offered some form of release.

15. Let’s stress-test that definition with a famous six-word story, allegedy written by Hemingway to win a bar bet.

For sale: Baby shoes, never worn.

Would Aristotle see a logically linked series of events? Is there a beginning or a middle? Implicitly, I suppose. You can sense the awfulness that led to this classified ad, even if it’s not on the page. How about resolution? Release? Nowhere in sight. What appears on the page is a broken middle. A beginning is implied, but a resolution is neither present nor promised. But (because I know it when I see it) this is unquestionably a story. So what makes it a story? What keeps it from being a mere anecdote? What essence of storyness does it possess?

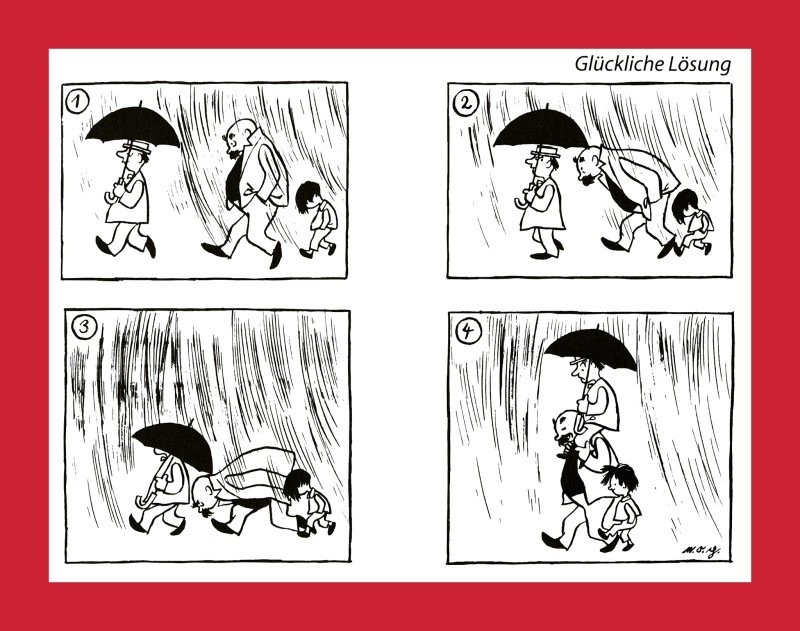

16. Narrative, according to the Sage Dictionary of Cultural Studies, “minimally concerns the disruption of equilibrium and the tracing of the consequences of said disruption until a new equilibrium is achieved.”

17. Let me unpack that. Essentially, this is three-act structure.

Act 1: You have the world as it is, in a state of (relative) equilibrium.

Act 2: Something happens and the world is disturbed. Here’s the disruption of equilibrium. Cue the struggle to regain equilibrium.

Act 3: The world is restored, but it’s not the same as it was in Act One. In fact, things will never be quite the same again.

18. Let’s apply this framework to the six-word story. For sale: Baby shoes, never worn. It’s all act two. No equilibrium to be found. Only disruption. So is that the kernel of the definition? Is disruption the only necessary component of a story. Not quite.

19. In his introduction to Henry James’s Art of the Novel, R.P. Blackmur writes that “James never put his readers in direct contact with his subjects; he believed it was impossible to do so because his subject really was not what happened but what someone felt about what happened, and this could be directly known only through an intermediate intelligence.” (emphasis mine)

19. In his introduction to Henry James’s Art of the Novel, R.P. Blackmur writes that “James never put his readers in direct contact with his subjects; he believed it was impossible to do so because his subject really was not what happened but what someone felt about what happened, and this could be directly known only through an intermediate intelligence.” (emphasis mine)

20. Last trip to the six-word story: For sale: Baby shoes, never worn. The story’s not about shoes. It’s not even about the baby, or his or her death. It’s about the parent dealing with tragedy by writing a classified ad. Disruption is essential to story, but a story is not about the disruption; the story is the reaction to the disruption. What happened is an anecdote. What someone felt about what happened is a story.

In “What Stories Are and Why We Read Them,” Ron Hanson asserts that “[w]hat stories try to present is generally sensory, how it feels to fall in love with Romeo and Juliet, to pursue a white whale across the Atlantic, to float in and out of consciousness within view of the snows of Kilimanjaro.” At play here is a beautiful reciprocity: you need to have what someone felt in order to have a story, and you need a story to truly access what someone felt.

21. Take another peek at that comic. Disruption and reaction and feeling—it’s all there. It’s a whole story.