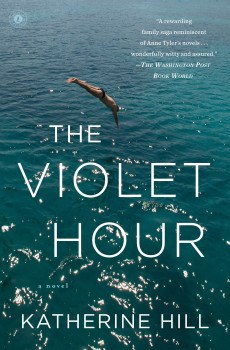

Unless you came from a perfect family, you’ll probably recognize many of the characters and their struggles in Katherine Hill’s The Violet Hour, which is just out in paperback from Scribner. This is a story of one family’s mistakes and path to forgiveness. A wife is unfaithful. A fragile marriage breaks. The patriarch of a family suddenly dies. A daughter stumbles on her own path toward love. The prose is lyrical and layered yet accessible. If you appreciate flawed people, you’ll love The Violet Hour.

If you are a T.S. Eliot fan, you’ll enjoy this novel even more. The title of The Violet Hour is taken from “The Waste Land,” which is considered one of the most important poems of the 20th century. In five sections, Eliot writes a critique of British society through the myths of the Holy Grail and the Fisher King. I thought of T.S. Eliot’s message throughout the novel and considered the additional challenges of navigating family in the modern world. The overarching message, which Hill provides and Eliot neglects, is the importance of forgiveness. Certainly any family could use more of that.

Katherine Hill was born in Washington, D.C. and now lives in Princeton, New Jersey. She holds a BA from Yale and an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars and is currently an Assistant Editor at Barrelhouse. Her fiction, essays, and reviews have appeared in numerous publications, including AGNI, Colorado Review, The Common, The Guardian, n+1, The Paris Review Daily, the San Francisco Chronicle, and the Wall Street Journal. In addition to being an author and an editor, Katherine has been a university speechwriter and a teacher in the New Jersey prison system. She is currently a visiting writer in the MFA program at Arcadia University.

Katherine and I met in a Facebook group of women writers. We chatted online, through email, and conducted this interview via Skype. Coincidentally, I now live and teach in the same part of Washington, D.C. where Katherine grew up. We’re both T.S. Eliot fans.

Interview:

Melissa Scholes Young: Am I reading too much into it to assume this is a nod to T.S. Eliot? Are you mirroring the collapse of society in “The Waste Land” with the collapse of this family?

Katherine Hill: Oh, I’m a huge fan. It’s a poem I’ve been rereading since high school. The mixing of memory and desire, the unreal city: those ideas gripped me from the very beginning. That said, the title was kind of a happy accident. One night over dinner my husband admitted he’d never read it. After feigning all kinds of shock and indignation (because, let’s be real, lots of intelligent, decent people haven’t read “The Waste Land”), I made him read it aloud with me. He was completely game, especially when I told him several famous novels had taken their titles from the poem—Doris Lessing’s The Grass Is Singing, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust. All of a sudden he was all fired up about my novel. I had just finished a draft at the time, and was still pretty shy about committing to a title, let alone shopping for one in such a famous poem. But lo and behold, we found one. And it actually worked.

Katherine Hill: Oh, I’m a huge fan. It’s a poem I’ve been rereading since high school. The mixing of memory and desire, the unreal city: those ideas gripped me from the very beginning. That said, the title was kind of a happy accident. One night over dinner my husband admitted he’d never read it. After feigning all kinds of shock and indignation (because, let’s be real, lots of intelligent, decent people haven’t read “The Waste Land”), I made him read it aloud with me. He was completely game, especially when I told him several famous novels had taken their titles from the poem—Doris Lessing’s The Grass Is Singing, Evelyn Waugh’s A Handful of Dust. All of a sudden he was all fired up about my novel. I had just finished a draft at the time, and was still pretty shy about committing to a title, let alone shopping for one in such a famous poem. But lo and behold, we found one. And it actually worked.

Did you find any other candidates while you were shopping?

Only hilariously bad ones. There was a lot of joking around about Hurry Up Please It’s Time and The Shouting and the Crying.

And if Eliot is critical of the Industrial Revolution, what do you see The Violet Hour as critiquing?

For me, it’s about the fault lines that underlie American affluence and its poster child the American family. The central characters, Abe, Cassandra, and Elizabeth Green, have built a family on all the values liberal turn-of-the-millennium Americans hold dear—passionate monogamy, individualism, engaged parenting, professional success. Sounds great, right? Yet those values are often in conflict. I actually think all three characters are basically decent people. They don’t really want to hurt each other, but they do, partly because they’re only human, but also because they’ve been profoundly shaped by a culture that sets them up for failure.

Let’s talk structure and opening scenes. Abe throwing himself off the boat is the make or break moment for the reader. I couldn’t turn the page fast enough, of course. I’ve heard agents say that writers don’t often know where their story begins. When did you know that was really the opening of this family’s story?

Oddly enough, the prologue was the very first scene I wrote. Don’t get me wrong, I revised it countless times, but the basics were all there in draft one. I was thinking a lot about The Tempest in those days, and the tradition of doomed love stories, and I just loved the idea of putting three allegedly responsible, modern people in a nearly impossible situation—both emotionally and physically—and then forcing us all to move on. I liked that their catastrophe had a mythic quality, but I also liked that it begged all sorts of earthly questions. How in the world can this happen in a family? What in the world happens next? The novel is an attempt at an answer, both for me and for my characters.

In your attempt to answer that challenge, what led to your decision to use third-person omniscient for all the characters? It seems a bold but risky choice.

For me, the perspective shift is one of the great powers and pleasures of writing fiction. Not that I’d be bored with one perspective—well, all right, I might be bored—but I think I’m just incredibly interested in people’s reactions to each other, both conscious and unconscious. All the messiness of social interaction, those complicated judgments and demands we make of each other. I also love imagining I’m someone else—someone of a different gender, age, body, background—so for me, it’s a pretty natural, if sometimes dizzying, way to approach a narrative.

The Violet Hour moves around a lot, much like the abrupt shifts in “The Waste Land.” We travel from the D.C. suburbs to San Francisco to Manhattan. Did you worry about grounding the story? How do you think multiple locations guides the telling?

This is probably similar to my desire to shift perspective. It’s fun to write about so many different places, each with its own attractions and repulsions. Its own banalities, its own myths. But it was also important to this particular novel to cover all that terrain. Cassandra and Abe are people who flee the East Coast for the West, and their daughter Elizabeth flees the West Coast for the East. That seems to me a pretty typical story among the striving professional classes today. I’m curious about this kind of American wanderlust—how ambitious it is, yet how narrow—and a novel is a great form for indulging curiosity.

Please tell me that you spent hours in a funeral home people watching. Corpse watching, too, yes?

In my childhood, actually, yes! My mother grew up in a funeral home in Brookfield, Illinois. I saw my first corpse, by accident, when I was about five or six, when my cousin and I went down to the chapel to play and no one remembered there was a body on the bier.

The image that probably stayed with me the most was when Cassandra’s mortician father takes her into the funeral parlor’s basement and encourages her to try her hand applying makeup to a corpse.

Oh, thank you so much, I’m pretty fond of that scene myself. Beauty and death go together more often than we might like to admit.

In addition to writer, you’ve worn a lot of occupational hats. Speechwriter. Teacher. Editor. How have these experiences influenced or informed your writing?

It’s no accident that every job I’ve ever had was in some way compatible with writing fiction—either because it offered an excuse to think and talk about fiction, or because it paid the bills while offering extra time to write. Looking back, I guess I’ve been pretty single-minded.

What was it like to teach writing at a correctional institute?

Incredible. If it’s something you’ve thought at all about doing, you really, really should. I’ve taught in prison twice now, in two different states, once with a class of older men and once with younger men, and both experiences felt so necessary and gratifying. It’s something I hope to do throughout my life.

Was it a difficult adjustment from a traditional classroom to a prison one?

It’s a little nerve-wracking at first with all the security, like going to the airport in 2002 twice a week, but once you’re through the gate, it’s more familiar than you might expect. There are classrooms with desks and white boards, and the students are incredibly motivated and eager to learn. I’m a secular person, but I felt almost religious about going inside. These students have so little. Education and the freedom to write are real gifts I can help give them

You’ll be sharing those gifts also this year as a visiting writer with the MFA program at Arcadia University. How do you juggle teaching and writing?

Probably like anyone does, with a mixture of ruthlessness and soft-heartedness. I know I have to defend my writing time, but I’m also pretty uncomfortable hoarding what I’ve learned when there are thousands of other writers out there trying to hack their way through the thicket as I once did (and am still doing). There’s a lot of pleasure in working with students.

Is it also tough to balance your editorship with Barrelhouse?

I was worried about that at first, but it’s actually been great. When the opportunity came up, I was a few years out of my MFA and deep in the muck of my novel. I was really trying to hoard writing time and worried about taking on too many other obligations. But they were like, “Hey, we understand how you feel, but we think you’ll like it, and if it gets too crazy, no hard feelings or anything like that.” It was totally the right approach. Now I can’t even imagine AWP without the zany home circus of the Barrelhouse table. Not to mention the joy of seeing stories I “discovered” published in the magazine. It really does feel as good as publishing a story of my own.

What advice do you have for writers seeking publication from an editor’s point of view?

My best advice is probably to submit only your very best finished work—not something you’re still revising or unsure of. Oh, and never take rejections personally. But we’ve all heard that, right?

On your blog you mentioned that you visited a book club in Maryland (where you grew up and where I live). What was it like to sit and listen to readers? Were they tougher critics than workshop?

Well, I loved my toughest writing workshops the most (probably because I’m some kind of masochist), but book clubs are a whole other breed of fun. Sometimes someone will get a little tipsy and tell you they hate your characters, but for the most part, being a book club guest is like being a fair queen. They sit you on the best chair and feed you their wonderful home-cooked food. And then they make all sorts of moving observations about literature and life and act as though you were somehow the source of them all. I’m blushing just thinking about it.

You and I are both fans of The Writer’s Center in Bethesda. You spent college summers working there, right? Is that when you first realized you wanted to be a writer?

I think I actually worked there because I wanted to be a writer. I processed memberships. I made the coffee. I drank milkshakes for dinner and spent the evening workshop hours browsing the shelves of books and literary journals. God, that was a great job.

What writers have influenced your work?

The all-time pantheon would have to include Virginia Woolf, Lorrie Moore, Jennifer Egan, and Zadie Smith. I probably would not have written The Violet Hour if not for Shakespeare and Jonathan Franzen. And it’s hard to imagine writing at all without Thomas Hardy, Edith Wharton, Lydia Davis, Mary Robison, Mary Gaitskill, Kazuo Ishiguro, Edward P. Jones, and Aleksandar Hemon. I’ll stop there, but only because I could go on listing influences forever. Even writers I disagree with have taught me important things.

This summer Poets & Writers published an article by Midge Raymond entitled “My Book is a Year Old, Now What?” about what to do when the paperback edition of your novel comes out. Have you prepared as much for your book’s second birthday as you did for the first?

I’m doing several readings and promoting it however I can. But I have to admit I feel much less anxiety for the paperback release, which is nice. People have read it now and some of them have even liked it, which was not a given last year. So, really, this time around, I just have to hope it stays in print. Which I guess it might not do. What was I saying about anxiety again?

I’m doing several readings and promoting it however I can. But I have to admit I feel much less anxiety for the paperback release, which is nice. People have read it now and some of them have even liked it, which was not a given last year. So, really, this time around, I just have to hope it stays in print. Which I guess it might not do. What was I saying about anxiety again?

Did the cover of the paperback—you write on your blog of “the gorgeous, half-naked man” diving into the water—cause anxiety or did you love it instantly?

You know, I don’t think I’ve ever loved anything instantly, but I trust my publisher. As it is, I’m always drawn to color and bold fonts. The real coup, though, was that the body objectified on the cover was a man’s and not a woman’s. As one friend put it, that’s practically a feminist victory.

Speaking of anxiety, what’s your next project?

Thank god for second projects! I’m currently in the throes of a novel about a professional football player and delighted to not yet be anxious about it.