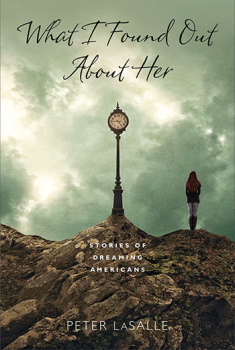

I read Peter LaSalle’s latest story collection, What I Found Out About Her: Stories of Dreaming Americans, in a Doubletree Hotel room in Dallas overlooking Central Expressway and in a motel room (Holiday Express) in Marshall, a small town in East Texas that produced the great quarterback Y.A. Tittle and was home for a number of years to the celebrated black poet Melvin B. Tolson.

The anonymous nowhereness of hotel/motel rooms is a perfect place to lose oneself in the often faraway stories of LaSalle, set in locations like Rio de Janeiro, Paris, Tunis, and Buenos Aires. In stories closer to home, in sites like New York, Austin, and Harvard Yard, LaSalle can create the same sense of strangeness about ordinary places, a sharp-focused evocation of the actual setting layered with memories, dreams, and the unexpected. The heart of the imagination in this book lies, I think, in the story “Tunis and Time.” There, gazing upon the ruins of the vanished civilization of ancient Carthage, the narrative voice in long looping sentences concludes, “But maybe here was also the overlooked truth about the dreaming, that everything was gone before it started…” while that too receives a lovely affirmative compensation, nevertheless, in the felt experience of actual life itself, as stated right after that in the story and how there surely is a “here and now that trumped everything….”

LaSalle and I have been colleagues and friends over thirty years. He joined the English Department at the University of Texas in the early ’80s, and around that time we both published books with the same press (Texas Monthly) and shared the usual ups and downs when the books came out—his a novel about urban Texas during the Sun Belt boom titled Strange Sunlight and mine a nonfiction meditation on film, Cowboys and Cadillacs: How Hollywood Looks at Texas. We both have always been writing, always talking a good deal with one another about our writing over the years as well. He is a voracious reader, and I know he has also made travel an integral part of his work as an author. His next book, which is currently going through final edit, I hear, will bring together the best of his many travel essays, which focus on world literature and are nonfiction of a high order. All in all, it seems LaSalle has indeed lived the literary life.

About his publishing background: Besides the new collection, What I Found Out About Her, released by University of Notre Dame Press last fall as the recipient of the Richard Sullivan Prize in Short Fiction, he has written several previous books, both novels and story collections. His stories have appeared in leading literary magazines and annual award anthologies, such as Paris Review, Zoetrope, Tin House, Antioch Review, Virginia Quarterly Review, Yale Review, Best American Short Stories, and Prize Stories: The O. Henry Awards. The book of literary travel essays just mentioned, The City at Three P.M., will be published by Dzanc Books in December 2015, and his story collection Tell Borges If You See Him, recipient of the Flannery O’Connor Award in 2007, will appear in Turkish and Portuguese (Brazil) translations later this year. He teaches creative writing at the University of Texas at Austin, in both the Department of English and the Michener Center for Writers graduate creative writing program.

Interview:

Don Graham: Pete, good to see the new story collection, What I Found out About Her. I’ve been reading your work for a while, as you know, have even included it in anthologies I’ve edited, and these short stories seem some of your best writing yet.

Peter LaSalle: Thanks.

One thing that struck me is that they build nicely on those in your last collection, Tell Borges If You See Him, in being concerned with the intersection of the dream world and so-called everyday life.

You know, that pretty much does get at what I’ve been after lately. And, you’re right, I do see the two books as going together and hopefully being complementary. I gave both of them subtitles to possibly produce a matching effect, so there’s Tell Borges If You See Him: Tales of Contemporary Somnambulism, and What I Found Out About Her: Stories of Dreaming Americans, with a thematic commonality overall, I guess. There’s a great quote from Borges that says, “We accept reality so readily, maybe because we suspect nothing is real.” I keep that in mind a lot when writing, more or less a ready motto. It sort of neatly encapsulates the ethos for much of my recent work, which is what I like to think of as a realistic surrealism, maybe. In this new collection there’s a wide cast of characters, most of them caught up in perhaps rocky times where their own lives do take on a dreamlike texture, somewhat that of a floating life and the feeling that the distinction between the real and the unreal doesn’t matter so much anymore.

You know, that pretty much does get at what I’ve been after lately. And, you’re right, I do see the two books as going together and hopefully being complementary. I gave both of them subtitles to possibly produce a matching effect, so there’s Tell Borges If You See Him: Tales of Contemporary Somnambulism, and What I Found Out About Her: Stories of Dreaming Americans, with a thematic commonality overall, I guess. There’s a great quote from Borges that says, “We accept reality so readily, maybe because we suspect nothing is real.” I keep that in mind a lot when writing, more or less a ready motto. It sort of neatly encapsulates the ethos for much of my recent work, which is what I like to think of as a realistic surrealism, maybe. In this new collection there’s a wide cast of characters, most of them caught up in perhaps rocky times where their own lives do take on a dreamlike texture, somewhat that of a floating life and the feeling that the distinction between the real and the unreal doesn’t matter so much anymore.

Such as in the story “The Dealer’s Girlfriend,” a good example, right?

Yes, it’s there in that story where a beautiful girlfriend of a well-to-do drug dealer in Austin, Texas, is in an emotional haze, plagued by loneliness and her own cocaine problem, so she tries to fill some looming vacancy in her life by becoming totally obsessed with a very poor child she sponsors in Brazil through one of those TV-solicitation feed-the-children charities.

In other stories, characters sometimes find themselves in odd binds equally as unsettling, I suppose—a burnt-out FBI agent in the story “Tunis and Time” sent on a seemingly meaningless mission to Tunisia to track down a suspected terrorist, or a trio of playwrights in New York in “Oh, Such Playwrights!” whose lives start to intertwine in spookily strange ways over the years

A few of the stories in this collection have epigraphs.

True.

You don’t often see that in short fiction, but they do seem to work effectively.

Maybe that’s another thing I do that could be offbeat, in addition to using a subtitle for the books themselves. I like the extra something you can get out of an epigraph, which, as you say, novelists are fully aware of but short story writers tend to avoid.

I’m thinking particularly of the epigraph you use from a precursor of Surrealism, the early French Symbolist poet Gérard de Nerval, in the brilliant story from Zoetrope magazine in the collection, “A Dream of Falling Asleep: IX-XVII,” where the epigraph says (let’s see, here it is), “Difficulties arose: events I could not fathom seemed to conspire against all my good intentions.”

The quote felt really right for that story, about a young guy teaching at the University of Michigan, a novelist who went to college on an ice hockey scholarship and now finds himself teaching creative writing as an exchange professor at a university in Paris. He has to deal with people who are close to him there in everyday situations while at the same time seeming to know exactly what will become of them in life, all who will suffer early deaths, actually. The Nerval quote hopefully does set the mood for the story and things spinning out of control for him, completely nightmarish, all right.

You appear to have been greatly influenced by writers in the Surrealist tradition.

There’s no denying that, but when I think of a tradition, I suppose I locate Surrealism itself in a larger one. I’d say it’s basically a metaphysical tradition and covers a long span of literary history and work from many countries. It includes the kind of daring, rather experimental writers I love, those who probably all aspiring writers like me were reading in the late 1960s and ’70s, an exciting, wide-open time and when I was lucky to have come of age as a writer. As you know, every couple of years I give a lit course in our graduate creative writing program here, the Michener Center for Writers, called “Metaphysical Messages.” Once a week I sit down with a dozen or so extremely bright and talented young writers who are the students for all of us to talk about, well, metaphysical writers, meaning those who challenge common assumptions about time and space as they maybe tap into something larger, transcendent even, with my learning as much from the students, surely, as they learn from me.

I think I’ve seen the reading list, but who exactly is on it?

We start with Baudelaire, because so much traces back to him. Then we stay on the French tack for a while with André Breton and Djuna Barnes, the American writer who was in Paris in the 1930s, when French Symbolism does become Surrealism around those years. And then we switch over to what I call “The Buenos Aires Connection,” with books by Borges, an iconic metaphysical author, of course, and inarguably the epicenter of the modern tradition, and María Luisa Bombal, a Chilean but a good friend of Borges and somebody who lived and wrote in Buenos Aires at that time. There’s next an intermission of sorts with a consideration of some painting, the usual mysterious suspects, such as Gustave Moreau, de Chirico, Magritte, and Paul Delvaux, then we finish off with more contemporary fare, specifically Nabokov and John Hawkes as novelists, also Beckett’s shorter plays and Mark Strand’s poetry.

My hope is that by seeing the possibilities shown in a more daring literature, also learning from painting, the students in the class—which includes mostly student fiction writers as well as some poets and playwrights, because the Michener Center is an interdisciplinary program—will begin to take risks in their own writing.

So you don’t think creative writing grad students are daring enough today.

No, I think they definitely can be, dazzlingly so, if somebody turns them on to work that will make them want to be daring, aspiring to write something fresh. The problem sometimes is that they haven’t seen much of this kind of writing before. As far as fiction goes, it’s no major secret that we’re living in quite conventional and commercial times today, or we are the U.S., anyway, yet the situation is certainly different—a whole lot more exciting—in Latin America or Continental Europe. Most college undergraduate literature classes don’t teach innovative work lately, and young fiction writers in grad programs are more used to the straightforward realism that appears in large-circulation magazines or books that garner big sales figures, so by definition the writing—though loudly celebrated—usually has to be pretty mainstream and traditionally realistic, for better or worse easily accessible nineteenth-century forms, actually.

What the grad students I deal with often do have is a wonderful, almost intimidatingly so, gift of language, beautiful sentences. If you couple that with sparking a youthful energy at their age and hopefully a desire to for once not think of just publishing and pleasing agents and editors at large publishing houses, but to wholeheartedly quest to break some artistic barriers, see what new subjects and innovative structures can be explored in using prose fiction to get at the important issues deep inside all of our lives—which is what good fiction is always about, the stuff of our hearts—then it can be amazing the work that such raw natural talent so applied will produce. This doesn’t mean abandoning the essentials of setting, character, and plot, which all yield an emotionally moving fiction. It has more to do with exploring and expanding on the possibilities of these essentials in either short story or novel writing.

Also, I should point out that several of the stories in my new collection, What I Found Out About Her, are surely much more traditional than others. To be honest, I’d say that in the end the only thing that ultimately matters in story writing is simply trying to create a strong and original narrative, plus always aiming to make every story a little tour de force, which is a what a truly successful short story should be, possessing that intensity—it’s why a story is so much different than a novel and special in a way. It really makes no difference what you call the writing when all is said and done, traditional or experimental or any other label you pull out of the hat.

Getting back to the subject at hand, the stories in What I Found Out About Her, there’s something else concerning the forms you sometimes use that I noticed.

You’re right, maybe I just did get a bit carried away with all that talk about a metaphysical tradition and that course I teach, the talk about mainstream literature, too.

No, I didn’t mean that, and what you just said was good. And this question is actually along those lines. In a few of the stories in this new collection, the sections and sometimes the paragraphs themselves are numbered—one story with Arabic numerals, another Roman numerals, another with the mark #. Besides being visually arresting, what did you have in mind with these structural devices? Donald Barthelme was the first writer I recall who did such, but as nearly always, there are probably earlier instances that I simply don’t know about. Or is this a completely Peter LaSalle thing?

I wouldn’t say it’s my own thing, by any means. And you are absolutely right, Donald Barthelme used similar devices, many other writers have, too. You know, now that I think of it, Barthelme perhaps did so because he was, in fact, director of a contemporary art museum in Houston and involved in that field before he started publishing stories. I suspect that knowing about modern painting—and subsequently the major breakthrough that collage afforded painters in the twentieth century—Barthelme was also very aware of the visual impact of a story, on the page, in addition to and part of the content of the narrative itself. This aspect of fiction is something that really first blossomed in modernism even well before Barthelme’s postmodernism, with Ulysses above all.

I wouldn’t say it’s my own thing, by any means. And you are absolutely right, Donald Barthelme used similar devices, many other writers have, too. You know, now that I think of it, Barthelme perhaps did so because he was, in fact, director of a contemporary art museum in Houston and involved in that field before he started publishing stories. I suspect that knowing about modern painting—and subsequently the major breakthrough that collage afforded painters in the twentieth century—Barthelme was also very aware of the visual impact of a story, on the page, in addition to and part of the content of the narrative itself. This aspect of fiction is something that really first blossomed in modernism even well before Barthelme’s postmodernism, with Ulysses above all.

For me, using numbers, Roman or Arabic, or the # sign—the latter which I see only as an intriguing, somehow ghostly mark that I use in one story where a young married couple can no longer communicate, and it has nothing whatsoever to do with the now trendy so-called hashtag online—all of these can create new combinations and valid modes of experiencing things for the reader, shaking up the standard look of narrative form and more accurately capturing the way our contemporary minds actually often operate, which isn’t always, if ever, reflected simply by the repeated and seamlessly connected-together blocks of print commonly called paragraphs. In the story we just spoke about, “A Dream of Falling Asleep IX-XVII,” the rather staggered, open-ended numbering in the title, and then in the text, was very intentional, and the idea was to give the feeling that the reader is just coming into the events somewhere in the middle of things and leaving the story the same way, which is how the successive reels of our dreams and night-imaginings seem to work. Does that make any sense?

Sure, very much so. And now for maybe one last thing.

OK.

You have another book coming out later this year, The City at Three P.M.: Writing, Reading, and Traveling, which is a collection of what I’ve heard you call literary travel essays. I write mostly nonfiction myself, but what is the distinction you’d make between a short story and the travel pieces that are in the collection? Or, maybe more specifically, is there a large difference in writing one or the other?

Let’s see. When young, I was a newspaper reporter for city dailies in what now seems a former life, before I began teaching at colleges and universities, and I’ve done a lot of other journalism over the years, too, so I soon realized its limitations. With you yourself being a writer who has produced so many books of your essays and nonfiction, you surely know as well as anybody that there is a very large difference between writing an article—which is usually journalism—and a bona fide essay. I try to see the nonfiction that I do now as essay writing, giving the opportunity for some depth in hopefully serious thought and also honest personal examination, no whitewashing—it’s possibly what gets categorized as creative nonfiction, though I’m not crazy about the term.

The label sure does seem to be in vogue lately.

In any case, when I travel nowadays it’s most likely to a place where the work of a great writer I admire is set, maybe Borges in Argentina or Flaubert in Tunis, site of his historical novel about ancient Carthage, Salammbô. I pack a small bag with enough clothes for a couple of weeks and bring some books by the writer and read them “on the premises,” so to speak, to see if anything different happens. I come out of it with both material for new fiction and usually a long travel essay with a definite literary angle, I guess, meaning I write about the author who interests me as much as I write of the place itself, then toss into the mix some pretty personal goings-on in my own admittedly sometimes tangled-up life.

One does rely a good deal on fictional technique in an essay of this sort—like lyrical language in spots and even some of those things I mentioned earlier, including collage and also stream of consciousness, to evoke the true tenor of travel to far-off places, which can have a dreamlike feeling, for me, anyway. You know, I’ve been going over the essays in the new travel-essay collection while correcting the copyedited manuscript this past week, especially some of the older pieces, like one about attending the happily ceremonial opening of a little bookstore in Cameroon years ago, or another about my life way back when I lived and traveled in Ireland when young, spending time with Christy Brown, the Irish writer who had cerebral palsy and typed with his toes, the subject of the Daniel Day Lewis film My Left Foot. Rereading some of that writing now, I see the scenarios as even more oddly dreamlike than when they were happening, almost as if I am simply experiencing it all in a dream and now wondering if it actually happened. Which it all did, of course, but that does evoke the old reality-unreality conundrum again.

Well, now that I’ve read the new story collection, it will be good to see how the travel described in the essays generated some of that fiction, and I look forward to the book.

Thanks again, Don, and thanks for all the good questions and dialogue here, too.

No, I thank you.

Let’s not get carried away with this Alphonse and Gaston thing.

I hear you.