Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose work we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

This week we’ve returned to Jacob M. Appel’s essay on subtext in the work of Dan Chaon, which was originally published on June 22 of 2015. Chaon’s newest book, Ill Will was released yesterday by Ballantine Books. Check back later this month for a new interview with Chaon, as well.

As a psychiatrist, my daily challenge is to uncover the latent emotions lurking beneath my patients’ manifest feelings and behaviors. As a writer of fiction, my task is precisely the opposite: to use the manifest actions and overt statements of my characters to convey to readers my characters’ hidden fears, passions, and conflicts, often sentiments of which these characters themselves remain tellingly unaware. In some ways, subtext—the workshop term for the unspoken aspects of fiction—is the craft element that separates immature writing from more sophisticated narration. Anyone who has ever read the prose of a gifted child knows this intuitively: the manifest content of the plot and setting will often prove vibrant and engaging, but the story will lack the hidden gems of nuance and subtle undercurrents of meaning that distinguish prose written by skilled adults. With ten year olds, what you see is what you get. Of course, serious readers of literature want to get more than they see. Among the most significant challenges an author faces is generating subtext that is neither so obvious that it runs the risk of drowning out the manifest story nor so understated that its impact is negligible. Anyone looking for a model should turn to the works of genre-bending maestro Dan Chaon, whose novels and stories—often perched on the cusp of magical realism and literary suspense—create an evocative, unsettling world by laying down stratum upon stratum of sinister subtext.

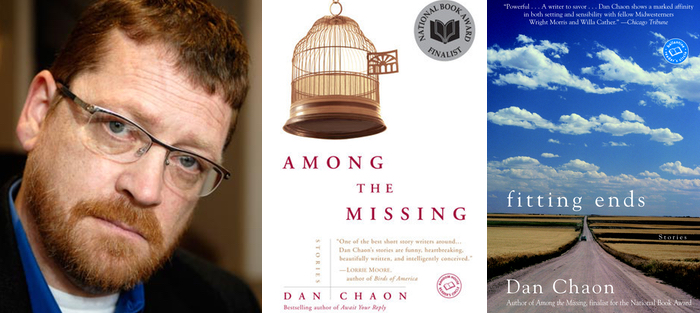

Chaon, whose surname rhymes with “lawn,” is a writer to admire for the hardscrabble trajectory of his career as much as for the mesmerism of his prose. The author has spoken of growing up a “ridiculously nerdy kid” on the outskirts of Sidney, Nebraska, and striking up a correspondence with Ray Bradbury at the age of thirteen. He published stories in respectable literary journals, including TriQuarterly, American Short Fiction, and Ploughshares, before finally putting out a first collection, Fitting Ends (1996), with Northwestern University Press at the venerable age of thirty-two. In the words of fellow novelist Thomas Barbash, the volume soon “quietly disappeared.” Undaunted, Chaon continued to generate stories, producing the widely-acclaimed collection, Among the Missing, a finalist for the National Book Award, in 2001. Only then did a major commercial publisher re-release Fitting Ends, garnering these earlier stories the critical attention they deserve. Two well-received and intricately-plotted novels, You Remind Me of Me (2004) and Await Your Reply (2009), followed. Yet it is in his stories, which have won the short fiction trifecta (Best American Short Stories, Pushcart Prize, O. Henry Award), where Chaon offers the aspiring writer the most accessible archetype for mastering subtext.

Subtext can be subdivided into three distinct elements: 1) the details of the milieu in which the characters exists, which can stimulate an emotional response from readers; 2) the nature and behavior of non-principal characters, designed to prime the readers expectations; and 3) the actions of the principal characters, intended to reveal their underlying emotional states. Archetypal Chaon stories, like the widely-recognized “I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me” and “Big Me” operate at all three levels. The subtext is so painstakingly structured that writing students can take the stories apart, piece by piece, like disassembling an engine—and, ideally, can learn how to create such stories on their own in the process.

“I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me” offers a retelling of the iconic crime story where the suspect’s guilt remains uncertain. The protagonist, Cheryl, moves to Cheyenne, Wyoming, with her lawyer husband, Tobe, and settles down alongside his “white trash” brothers: Carlin, “a policeman, crew-cut, with the face of a bully”; lonesome, alcoholic Randy; and intelligent yet inscrutable Wendell, who charms Cheryl by performing classical music on his piano at one moment and then offends her by telling a racist joke an instant later. Before the story begins, Wendell has been convicted for perpetrating a series of brutal sexual assaults at a trial where Cheryl’s husband, whose training is in family law, acted as defense counsel. The narrative follows Cheryl as she grapples with the aftermath of the conviction and the appeals process, during which she is tasked with looking after Wendell’s pet macaw, Wild Bill, a creature endowed with a penchant profane expressions. By peppering his prose with subtle, sinister details, Chaon manages to create a subtext of tension that supports the weight of the story’s content.

“I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me” offers a retelling of the iconic crime story where the suspect’s guilt remains uncertain. The protagonist, Cheryl, moves to Cheyenne, Wyoming, with her lawyer husband, Tobe, and settles down alongside his “white trash” brothers: Carlin, “a policeman, crew-cut, with the face of a bully”; lonesome, alcoholic Randy; and intelligent yet inscrutable Wendell, who charms Cheryl by performing classical music on his piano at one moment and then offends her by telling a racist joke an instant later. Before the story begins, Wendell has been convicted for perpetrating a series of brutal sexual assaults at a trial where Cheryl’s husband, whose training is in family law, acted as defense counsel. The narrative follows Cheryl as she grapples with the aftermath of the conviction and the appeals process, during which she is tasked with looking after Wendell’s pet macaw, Wild Bill, a creature endowed with a penchant profane expressions. By peppering his prose with subtle, sinister details, Chaon manages to create a subtext of tension that supports the weight of the story’s content.

Hints of violence abound. Cheryl’s brothers-in-law, the reader learns, are “close in an old-fashioned way, like brothers in Westerns or gangster films.” Her late father-in-law was “a man who got into fistfights in bars.” As a child, Cheryl’s husband was “abused by a group of high school bullies” until his brothers “caught the boys after school, one by one, ‘and beat the living shit out of them.’” The phrase “one by one” adds a premeditated, systematic aspect to the earlier violence that parallels that of the alleged rapes. From prison, in an ominous gesture, Wendell sends Cheryl’s young daughter a hand-sketched birthday card depicting a spotted leopard “crouched as if hunting.” Yet if the backdrop of the story is pregnant with violence—and particularly hints of sexual violence—it also holds suggestions of impending loneliness and isolation. Cheryl’s mother, for instance, was “now divorced for a third time” and “lived alone on a houseboat near San Diego.” We are reminded, as readers, that this loneliness is a danger Cheryl herself faces too; she even recognizes this threat: “In a few brief moves, she could easily isolate herself—the bitchy city girl, the snob, the troublemaker.” The fate of her mother is the subtext that adds power to her own fears.

Cultural references also further the story’s themes. I warn my own creative writing students that allusions to other works of art or literature prove effective only when they mirror the tone or content of the narrative in a meaningful way, and Chaon chooses his references with perfectly-pitched precision. While her husband and brothers-in-law play drunken Monopoly, Cheryl reads Edith Wharton’s The House of Mirth—possibly the paradigmatic cautionary tale for women exploring romance outside their own social circles. Wendell and the parrot each adopt the expression, “What a world, what a world,” quoting the Wicked Witch of the West as she melts in The Wizard of Oz; in doing so, both man and bird foreshadow their own self-induced destructions. The three composers Wendell plays on the piano, “Debussy, then Gershwin, then an old Hank Williams song,” all led lives marked by romantic turbulence that ended in premature deaths. Even the wall art in the visiting booth of Wendell’s prison serves a tonal purpose: a “mural of a rearing mustang with mountains and lightning behind it” emphasizing its contrast to the restrictions of Wendell’s confinement and simultaneously supplying a reminder of the loneliness of the outside world. Similarly, the weather is harnessed to convey the hopelessness of Cheryl’s situation: “She sat in her office, in the high school, and she could see the distant mountains out the window, growing paler and less majestic until they looked almost translucent, like oddly shaped thunderheads fading into the colorless sky.” Later, after “a haze settled over the city,” snow arrives and the “end of daylight savings time” leave her in a “darkness” that mirrors the “silent, malevolent presence” of her brother-in-law’s bird. None of these details, taken individually, are likely to have much effect on an average reader. Collectively, however, they create a milieu or backdrop suited for the story—one that helps the reader anticipate and digest the violence and isolation of the plot.

This milieu creates room for the second element of subtext: small actions by minor characters that collectively build tension—often with the readership hardly noticing. In “I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me,” the primary vehicle for this variety of subtext is Wendell’s macaw, Wild Bill. The bird has been trained, presumably by Wendell, to express himself in ways not suited for polite company. Often, these expressions are then absorbed and repeated inappropriately by Cheryl’s children. One evening at dinner, her son and daughter take turns repeating the birds’ catchphrase, “Smell my feet,” until Cheryl loses her temper. The expression “bothered her more than she could explain. It was silly, but it sickened her, conjuring up a morbid fascination with human stink, something vulgar and tiring.” The phrase reminds the reader of two other details that render it far more sinister: the modus operandi of the local rapist has been to force his victims to lick his feet, while Cheryl has been charged with the responsibility of cleaning away “the excrement-splashed newspaper” at the bottom of Wild Bill’s cage. In other words, the macaw’s obscenity links her to the sex crimes. In a subsequent scene, Cheryl serves her son a casserole “which reminded her, nostalgically, of her childhood,” and the boy responds, “Mmmm…Smells like pussy.” Once again, the bird’s vulgar vocabulary, conveyed through her own offspring, connects Cheryl to the violence of which her brother-in-law is accused.

Toward the end of the story, Wild Bill begins to “pull out his own feathers distractedly,” as part of the molting process; he finds his “naked flesh” exposed shortly before he is violently attacked—not unlike the rapist’s victims. It is important to note that Chaon’s story is not about Wild Bill, but about Cheryl and Wendell. (In this way, it differs from other talking bird tales, like Robert Olen’ Butler’s “Jealous Husband Returns as Parrot” and my own “Shell Game with Organs,” in which the birds themselves play a principal role.) The language and behavior of the avian foil here merely create a context in which the main characters can operate.

The third element of subtext—and as a psychiatrist, the variety of subtext I find most intriguing—exposes the main character’s psyche through her actions, often revealing secrets of which the character herself remains unaware. Early on, we sense Cheryl’s apprehension of violence to come when she refuses to allow the family to store Wendell’s shotguns at her house while he is incarcerated. Yet her burgeoning anger and despair grow clearer after her brother-in-law phones her from prison and professes his love for her. In contemplating a response, Cheryl reflects that “she could summon up the part of herself that was like a guidance counselor at school, quick and steady, explaining to students that they had been expelled, that their behavior was inappropriate…that thoughts of suicide were often a natural part of adolescence but should not be dwelled upon.” Nothing in the manifest content of the story gives Cheryl any reason to think of suicide at that moment, so a psychiatrist isn’t required to read into these thoughts the depth of her helplessness and despair. Similarly, she wonders, “How was it possible that they could let him call her like this, unmonitored? She was free to hang up, of course, that’s what the authorities assumed. But she didn’t.” Why not? Possibly because a part of her agrees with Wendell when he says that “things would be different for me if we’d…if something had happened, and you weren’t married. It could have been really different for me.” And for Cheryl. Earlier, she has observed that Wendell was “a younger and—yes, admit it—sexier version of her husband.” Now, in the course of a conversation with her imprisoned brother-in-law, she finds herself perversely drawn to a convicted rapist; at the same time, the elements of Wendell that she recognizes in Tobe drive her away from her husband, which helps to explain why, after her brother-in-law hangs up, she “considered picking up the phone and calling Tobe at his office,” but didn’t. As readers, we understand that her ambivalent feelings toward Wendell have shattered her marriage, even if she hasn’t yet consciously recognized this. In her own words, “she had to get her thoughts together.”

The third element of subtext—and as a psychiatrist, the variety of subtext I find most intriguing—exposes the main character’s psyche through her actions, often revealing secrets of which the character herself remains unaware. Early on, we sense Cheryl’s apprehension of violence to come when she refuses to allow the family to store Wendell’s shotguns at her house while he is incarcerated. Yet her burgeoning anger and despair grow clearer after her brother-in-law phones her from prison and professes his love for her. In contemplating a response, Cheryl reflects that “she could summon up the part of herself that was like a guidance counselor at school, quick and steady, explaining to students that they had been expelled, that their behavior was inappropriate…that thoughts of suicide were often a natural part of adolescence but should not be dwelled upon.” Nothing in the manifest content of the story gives Cheryl any reason to think of suicide at that moment, so a psychiatrist isn’t required to read into these thoughts the depth of her helplessness and despair. Similarly, she wonders, “How was it possible that they could let him call her like this, unmonitored? She was free to hang up, of course, that’s what the authorities assumed. But she didn’t.” Why not? Possibly because a part of her agrees with Wendell when he says that “things would be different for me if we’d…if something had happened, and you weren’t married. It could have been really different for me.” And for Cheryl. Earlier, she has observed that Wendell was “a younger and—yes, admit it—sexier version of her husband.” Now, in the course of a conversation with her imprisoned brother-in-law, she finds herself perversely drawn to a convicted rapist; at the same time, the elements of Wendell that she recognizes in Tobe drive her away from her husband, which helps to explain why, after her brother-in-law hangs up, she “considered picking up the phone and calling Tobe at his office,” but didn’t. As readers, we understand that her ambivalent feelings toward Wendell have shattered her marriage, even if she hasn’t yet consciously recognized this. In her own words, “she had to get her thoughts together.”

The close of the story, in which Cheryl murders Wild Bill, offers another example of latent revelations preceding manifest action. After the macaw begins to molt, Cheryl finds herself thinking that “his body was similar to the Cornish game hens she occasionally prepared, only different in that he was alive and not fully plucked.” In other words, she has already started to break down the barriers that separate the crude bird from dead meat. As readers, we can anticipate her willingness to butcher the macaw, even if she does not.

Every aspect of “I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me” reflects a complex interplay between story and subtext—including the title. Rather than end his narrative focused on Cheryl and Wendell and Wild Bill, Chaon shifts obliquely to the content of the television show that is playing in the background during the bird’s demise:

The rich lady on the television was being kidnapped as Wild Bill slapped his wings once more, weakly, against the windows. Cheryl watched intently, though the action on the screen seemed meaningless. “How dare you!” the rich lady cried as she was hustled along a corridor…. “I demand to know where you’re taking me,” the elegant woman said desperately, and when Cheryl looked up, Wild Bill had fallen away from his grip on the windowsill.

To Cheryl, this violent television scene seems “meaningless” and unrelated to her own experiences with her husband’s family. As readers, of course, we immediately recognize the connections that Chaon has drawn between these two worlds.

A more experimental and innovative use of subtext occurs in “Big Me,” which first appeared in The Gettysburg Review and later won second place in the 2001 O. Henry Prize anthology. The complex story is narrated retrospectively by Andy O’Day, who relates both his experiences growing up in the miniscule town of Beck, Nebraska, and his childhood fantasies of a parallel metropolis in the nearby hills where he imagined himself as the “city Detective.” These two worlds collide when twelve-year-old O’Day encounters his new neighbor and future science teacher, Louis Mickelson, whom he believes to be his own “grown up” double. All three traditional aspects of subtext are present, just as in “I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me.” For instance, at the level of milieu, Andy’s parents own a bar called The Crossroads during this brief interval of time that happens to mark both a turning point in their marriage and in Andy’s development. Cultural cues also convey sinister meanings: When Andy decides to keep an ill-fated journal—a journal which he will later have wrenched from him as his childhood innocence is shattered—the inspiration for his writing is nothing less than The Diary of Anne Frank. The plaque hanging in Mickelson’s living room echoes Dickens’ A Christmas Carol: “I wear the chain I forged in life.” A quotation of this sort serves two related purposes: On the one hand, it sets an ominous tone, while on the other, it foreshadows the downfall of its hard-drinking owner.

Chaon also builds tension through the actions of the minor characters, but does so in a highly unconventional way. Since the story is told retrospectively, the author can use the future actions of characters to prime the readers’ expectations. The primary victims, in this regard, are the narrator’s relatives. Their fates are revealed incrementally throughout the narrative, adding to the ominous aura of suspense. We learn that O’Day’s sister has “suffered brain damage in a car accident” at age nineteen, that his father has died of cirrhosis, that his brother “spends his time reading books about childhood trauma” and wallowing in despair. These future events, known to the adult narrator but not the child protagonist, cast a grim shadow over the story.

Unlike Cheryl in “I Demand to Know Where You’re Taking Me,” the distanced perch of Andy O’Day’s narrative gives him far more insight into his own actions. The risk of such insight, to draw from my psychiatric background, is that little daylight exists between O’Day’s understanding of his actions and our own analysis of his actions. In head-shrinker parlance, you might say he has become well-adjusted—even cured. Fortunately, Chaon takes advantage of the unusual structural devices of the parallel cities and the parallel versions of the narrator (young Andy and grownup Louis) to send O’Day in search of his own subtext. As city Detective, and again as an adult narrator, O’Day joins the reader on a mission to interpret his own actions.

O’Day overtly acknowledges the distance between the latent and the manifest. “My family thought of me as a certain person,” he tells the reader, “a figure I knew well enough to act out on occasion. Now that they are far away, it sometimes hurts to think that we knew so little of one another. Sometimes I think: If no one knows you, then you are no one.” Complicating matters further, the young O’Day begins writing messages to his future self, “Big Me, or The Future Me,” which contain warnings such as “I hope you are not a failure” and “I hope you are happy.” The all-consuming goal of the young O’Day is to decipher the clues about his double, Mickelson, whom he thinks of as his future self. One afternoon, he sneaks into the teacher’s house to investigate and discovers a trove of such clues: “The drawers themselves lay on the floor and contained reams of magazines that he’d saved. Popular Science in one, Asimov’s Science Fiction in another, Playboy in yet another, though the dirty pictures had all been fastidiously scissored out….You can imagine that this was like a cave of wonders for me, piled high with riches, with clues, and each box almost trembled with mystery.” As readers, we are aware that adult O’Day is sharing these particular details for a reason, hinting that these magazines, down to the missing centerfolds, might mirror the remaining artifacts of his own childhood. Yet the narrator also has the insight to recognize that he cannot fully understand himself: “I’d sift through the cigar box full of things I’d taken from his home: photographs, keys, a Swiss army knife, a check stub with his signature, which I’d compared against my own. But nothing seemed to fit. All I knew was that he was mysterious. He had some secret.” The target of this inquiry, Louis, both is and simultaneously is not the adult O’Day, so the narrator’s inability to decipher his double also becomes an inability to decipher himself. Chaon uses this device to create worlds of meaning trapped within each other, like Russian nesting dolls. That is subtext at its finest.

One particular passage from “Big Me” demonstrates these many techniques combined at their strongest:

That night, considering the encounter, I wondered whether the man actually was me. I thought about all that I’d heard about time travel, and considered the possibility that my older self had come back for some unknown purpose—perhaps to save me from some mistake I was about to make, or to warn me. Maybe he was fleeing some future disaster, and hoped to change the course of things. I suppose this tells you a lot about what I was like as a boy, but these were among the first ideas I considered. I believed wholeheartedly in the notion that time travel would soon be reality, just as I believed in UFOs and ESP and Bigfoot. I used to worry, in all seriousness, whether humanities would last as long as the dinosaurs had lasted. What if we were just a brief, passing phase on the planet?

At first, we have the young protagonist in his quest to understand the thoughts and actions of the character he imagines to be his adult self. And then we have the adult narrator using the fact of that quest to grapple with his own identity as a child. Both these layers of exploration are wrapped in the sinister context of the supernatural, hinted at with references to extraterrestrials and crypto-hominids, and punctuated with the possibility of the species’ forthcoming extinction. What more could a writing student ask for in a model?

Writers intuitively know that literary fiction must work on multiple levels. Masters of subtext like Chaon, like Willa Cather and Shirley Jackson before him, understand that every detail and image and minor gesture must do the same. Whether it is Trent in Chaon’s “Late for the Wedding,” seeing “a poster of a wolf behind the couch” that his mother is sitting on and realizing he is no longer welcome in his childhood home, or the “bar code” Harry tattoos on his forehead in Chaon’s “Burn With Me” that announces to the reader his emotional detachment from his family, The author understands that these gems have to shine at both levels in order to succeed.

Much as young children create stories that operate entirely in the manifest world of plot and dialogue, where characters say precisely what they mean, many aspiring adult writers fall into the trap of crafting stories that are all nuance and subtext—in which plotlines are negligible, symbols heavy-handed and characters enslaved to hidden meanings. Between these two snake pits runs a narrow ridge where details work simultaneously at both the literal and symbolic levels, and where characters take actions that are consciously motivated, yet revealing of unconscious yearnings. In the hands of a master of subtext, like Chaon, those details can function effectively at three or four or five levels. Even with my years of psychiatric training, I can analyze them afresh with each reading and still discover additional layers of meaning.