The most powerful earthquake of recorded Japanese history struck March 11, 2011, and triggered a devastating tsunami. Waves cresting at 23 feet slammed into the eastern coast. Images of apocalyptic destruction flooded the media: ruptured roads, crumpled cars, houses crushed to matchsticks, blazing fires, ships tossed inland, and desperate survivors seeking loved ones. Worlds away, I searched my bookshelf for Pearl S. Buck’s The Big Wave, a book I first read as a nine-year-old during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and to which I still return at difficult times.

The most powerful earthquake of recorded Japanese history struck March 11, 2011, and triggered a devastating tsunami. Waves cresting at 23 feet slammed into the eastern coast. Images of apocalyptic destruction flooded the media: ruptured roads, crumpled cars, houses crushed to matchsticks, blazing fires, ships tossed inland, and desperate survivors seeking loved ones. Worlds away, I searched my bookshelf for Pearl S. Buck’s The Big Wave, a book I first read as a nine-year-old during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and to which I still return at difficult times.

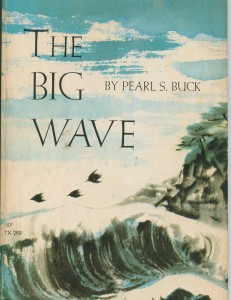

The brief volume’s slim spine almost disappeared between bulkier neighbors. On the cover, three brush-stroked birds skim a cresting wave; a few more lines suggest a fringe of evergreens straggling down a jagged cliff into the surf.

I opened the frail paperback. Across the flyleaf, my name and childhood address staggered in block letters. Tucked inside was a sheaf of folded wide-ruled notebook paper: my youngest daughter’s third-grade homework from a dozen years ago, when she read my heirloom copy. Now, I began again to re-read Buck’s tale of Jiya, the lone survivor of his family after another Japanese tsunami.

Warned by a “strange fiery dawn,” Jiya’s father insists his youngest child leave the rest of the family on the beach for safety on the mountainside. Jiya takes shelter with his friend Kino’s family on their farm, and the boys witness the tsunami’s terrible beauty:

The purple rim of the ocean seemed to lift and rise against clouds…With a great sucking sigh the wave swept back…dragging everything with it, trees and stones and houses…the beach was as clean of houses as if no human beings had ever lived there.

Devastated by grief, Jiya is fostered by Kino’s family. Kino cannot imagine how his friend will ever be happy again, but Kino’s father promises that “life is always stronger than death.” Time passes, “split in two parts by the big wave.” Jiya grows up farming beside his friend. He falls in love with Kino’s sister, Setsu. “Happiness began to live in him secretly, hidden inside him.” However, when Jiya sees people re-building the fishing village, he becomes restless and announces his need to return to the seaside. Kino’s father supports his intention and pays him wages for farming. Jiya buys a boat, strings nets, and builds a house on the shore for himself and his bride Setsu. The house is a copy of his childhood home, except for one innovation: windows facing the sea. “I have opened my house to the ocean,” he tells Kino on the last page. “If ever the big wave comes back, I shall be ready. I face it. I am not afraid.” Although Kino fears for his friend on the beach, his father reminds him no one is safe anywhere and says, “To live in the midst of danger is to know how good life is.”

The Big Wave drew on Buck’s recollections of a sojourn on the Japanese coast. In 1927, she and her husband – both professors at the University of Nanking – fled China to escape the violence between the Nationalists and the Communists. They settled in relative safety on the slopes of a volcano in Unzen, Japan. While there, she witnessed a tsunami sweep away the fishing village below, learned of prior tidal disasters in the community over the centuries, and watched the villagers rebuild as before, on the same beach. Buck explains in her introduction to my 1962 Scholastic Books edition that she wrote the story shortly after World War II, because children everywhere had learned that “death comes even to the young.” She wrote it to help children learn to “live in the presence of death, as we all do, young and old.”

The book arrived on my fourth grade desk in my monthly book order. How had I chosen it from the Scholastic Book Services flier? It was likely that my mother, a primary school teacher, knew of the book, a winner of The Child Study Association Children’s Book Award. I don’t recall her prompting me to select it, though later she stockpiled multiple copies of the same fifty-cent Scholastic reprint as a sympathy gift for students or friends suffering a loss.

As it happened, the book fell into my hands just when I needed it most: in the autumn of the Cuban Missile Crisis. That weekend in October 1962 felt ominous in the suburbs of Washington, D.C. Despite the blue of the fall sky and the golden leaves of tulip poplars, I felt a shivery sense of threat. Some of my friends’ families left town, but we remained at home. I retreated to my bedroom and lost myself in my new book and the familiar comfort of reading: inhaling the aroma of cheap paper and ink, turning the rough pages.

Buck’s description of the thatched houses on the beach – “frail wooden houses the big wave could lift like toys and crush and throw away” – particularly resonated with me, as I hid from Castro up in my bedroom under the eaves. That afternoon, my own home also felt flimsy, frail, and under threat.

Our house was a contemporary modular design, a franchised kit house called a Techbuilt designed by Karl Koch, an architect inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright and, like Wright, by Japanese architecture. Floor-to-ceiling windows and sliding glass doors unified the interior with the natural space outside. No attic, no basement, no place for a fallout shelter. No place to hide. Our house was as open as the house Jiya built on the beach with big windows facing the sea. And my parents’ house, like Jiya’s, was built by survivors to prove that life is stronger than death.

West Hill Drive (1999)

Growing up in Illinois, my parents had never seen a dwelling like a Techbuilt. As newlyweds, they moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, so my father could attend graduate school on the G.I. bill. They shared a small flat with a dour elderly woman before moving to the relative luxury of an attic apartment above the school where my mother taught. Then they visited friends renting a Techbuilt in Lincoln. They fell in love with the airy, open-plan house.

After my father finished school, they moved to junior faculty housing on the campus of Haverford College. I arrived, and my brother, Hugh, followed eighteen months later. We might have grown up as faculty kids, in a rambling Victorian on College Circle. But, when I was three, my brother died. Hugh’s death – though I cannot recall it – was the transforming event of our lives, the big wave demarcating our “Before” and “After.” I grew up in a family defined by the unspoken understanding that life is precious, and provisional.

We moved to Bethesda, Maryland where my father had accepted a job offer at the National Institute of Mental Health. Barely three months after losing Hugh, my mother was pregnant again, and she and my father were preparing to construct their own Techbuilt.

I cannot remember the hours they spent dreaming that house into existence, playing with a three-dimensional planning kit my father designed, so they might juggle modular room-blocks in various patterns and configurations. Now, I marvel at the bravery required to invest in the future with a pregnancy, a move, a new house, a new job – all so soon after losing Hugh.

My mother would say they did it because you must. Like Kino’s father, she believed that life is stronger than death. Now, when I think of her giving The Big Wave to bereaved friends and students, I wonder if she knew and empathized with of Buck’s own maternal history: the author’s biological daughter profoundly disabled due to phenylketonuria, seven adopted children, activism on behalf of orphans considered unwanted. My second brother, Don, was born in January, 1957. All children are prized, but Hugh’s death rendered Don’s life even more precious to my parents. As Kino’s father says, “Every day of life is more valuable now than it was before the storm.”

My parents planned, broke ground, and built their house after Hugh’s death in the manner of all survivors: out of necessity, denial, and hope. Like Jiya, they put windows in their house – a sheer skin of glass the architect intended to “provide bright sunlit rooms…bringing in the whole outdoors.” We moved into the new house in April for my mother’s thirty-third birthday. She remembered being so happy she could not sleep. Even after many memories departed her in the fog of dementia later, she remembered the white blossoms of the native dogwood tree shining beyond the curtain-less expanse of glass.

Those sheer glass walls might have felt insubstantial to me that weekend in October 1962, but my parents loved the open house and its wooded setting. They sited the house with respect to the sloping lot in a forest of pine, tulip poplar, dogwood and beech. Even as parsimonious children of the depression, they splurged and hired a landscape architect. Lester Collins had studied in the Far East and designed according to ancient Japanese principles with reverence for topography and symmetric balance. For a child the best feature of Collins’s design was not the moss garden nor the patio’s expanse of blue-gray gravel, but his meandering circuit of irregular wood-chip paths through the trees. My parents worked hard to implement his vision: spreading wood chips and gravel, transplanting and encouraging native flora. They planted bulbs every fall in the early years to multiply, naturalize and eventually carpet the woods with snowdrops, crocus, wood anemones, scilla, and daffodils.

Earlier in that October week of the Cuban Missile Crisis, my father had received a mail-order treasure: a bushel of daffodil bulbs from Holland. He summoned me outside for yard work on that brilliant, ominous fall day. With typical resolve and common sense, he intentionally brought me out into the world. Like Kino’s father, mine would have said, if he were more of a talker – “To live in the midst of danger is to know how good life is.”

Many years later, my father described planting those bulbs as an “exercise in suburban defiance” and claimed with his trademark wry humor that the bulbs had indeed proved good deterrents. “No missiles yet,” he said.

No missiles yet, but house and woods and flowers have vanished. When my parents moved from their beloved Techbuilt on the eve of my mother’s seventy-fifth birthday – a departure necessitated by the gathering storm of her dementia – the daffodils were in bloom. I gathered armloads. The new owners never missed the stolen flowers; the white dogwood bathed in moonlight never kept them awake. They never even slept in the house before smashing it, shattering the windows, bulldozing the acre of trees and flowers to build their own dream mini-mansion surrounded by sod and asphalt.

Although only bricks and mortar and the flowering woods were lost, I grieve for the house. No missiles, no tsunami, just the tedious work of a bulldozer; the commonplace destruction of one house so another can take its place. In comparison, how unimaginable the grief wrought by the big wave which swallowed Jiya’s family and village, or the March 2011 tsunami.

Aerial view of the Fukushima I plant area in 1975, showing sea walls and completed reactors via National Land Image Information (Color Aerial Photographs)

The March tsunami drowned twenty thousand, cracked the Fukushima Daiichi plant, and triggered a continuing, insidious wave of devastation. Six months after the tsunami, Prime Minister Naoto Kan bowed and announced his resignation amidst the widening tide of nuclear contamination discovered in crops, fish and beef far beyond Fukushima Daichi’s immediate locale. Now, despite the invisible and uncertain threat, evacuees are returning to the region just outside the no-entry radius; perhaps needing to jump-start life despite lingering uncertainty, residual danger. Schools in Fukushima scrape the surface layer of contaminated soil away and store it in plastic-lined pits: an inadequate solution. Children play there again. No one knows the long term effects of playing on the tainted ground.

I can’t stop thinking about how the destructive impact of this most recent tsunami has not yet ended. After every tsunami the threat of recurrence remains; as Kino’s father said, “On any day ocean may rise into storm and volcano may burst into flame.” But after the March tsunami, an active danger persists – radiation. Radioactive cesium may persist for three hundred years, bound to earth, in the silt in water.

But the children go back to the playground. We must let them play, Pearl S. Buck and my mother might say, even when the world is ruined and dangerous. My brother Hugh’s memorial at Haverford is a sandbox beneath a gnarled Osage orange tree. Children dig in the sand and clamber on the tree where we once played.

Before returning my shabby paperback copy of The Big Wave to the shelf, I read my daughter’s homework penciled in her careful beginner cursive a dozen years ago. She was nine, about my age at first reading, and Jiya’s and Kino’s age when the big wave struck. She wrote:

When Kino’s father says “we love life because we live in danger” he means they love life because they will not always have it. Also that they will not be able to enjoy life when they are dead…I agree with Kino’s father because they will not live forever.

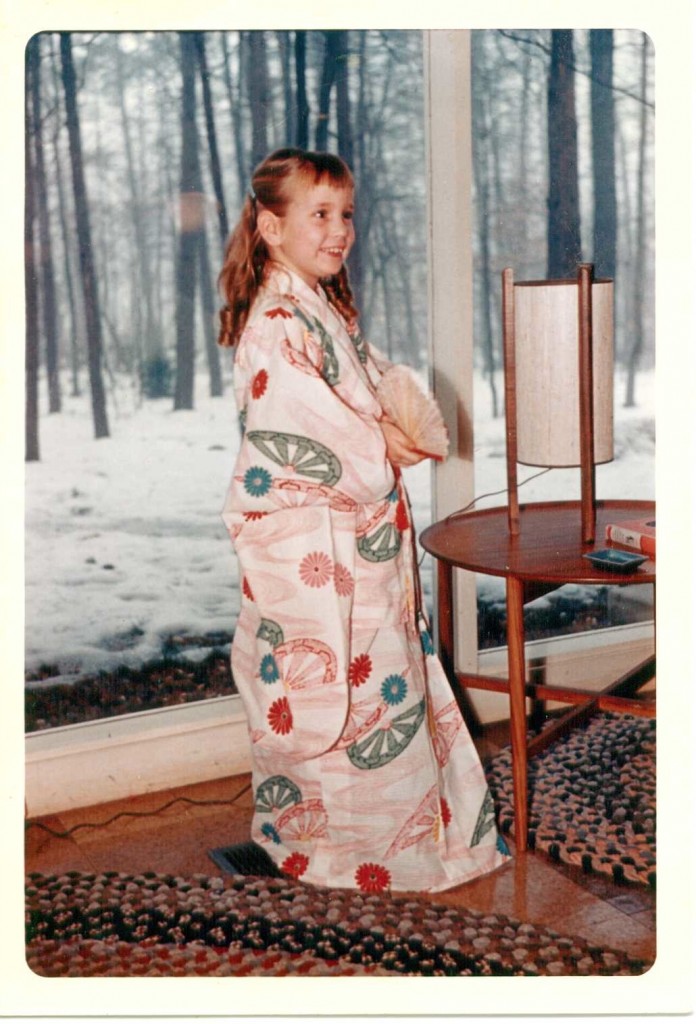

Ellen at Home (1962)

Planting bulbs, building houses are both acts of creative defiance; gestures we make, knowing we can’t live forever. Writing is the ultimate act of creative defiance. I think of Pearl S. Buck on the slopes of a volcano, writing a story of loss and survival. Her voice lives on in her story of resilience and re-creation and will long outlast my fragile copy of The Big Wave.

Further Links and Resources:

- Read more about architect Carl Koch and his Techbuilt homes in a 2010 article on the Dwell Website.

- Read more about Pearl S. Buck, the first American woman author to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, on the University of Pennsylvania’s English Department Website.