Let’s talk, you and I. Let’s talk about fear.

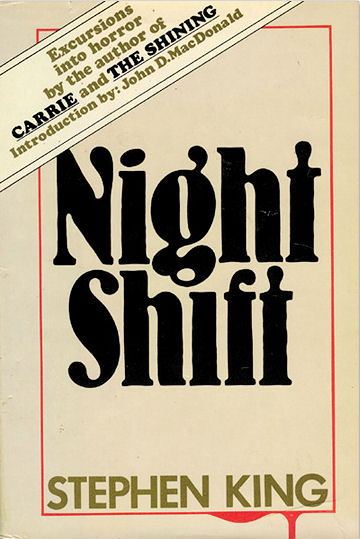

The idea that a scary story resembles a rollercoaster—that each provides the thrill of genuine fear within the safety of certain confines—is now cliché, but truth breeds clichés. Stephen King is arguably the reigning champion of inducing fear as far as authors go. For decades he has delighted readers with tales of the scintillating and sadistic, but his powers are perhaps at their best in Night Shift. King’s first short story collection takes advantage of the “safe” scare, but the collection’s real artistry is in accessing his reader’s willingness to endure “safe” fear and turning it on the reader himself.

Collected in 1978, Night Shift includes mainly stories published in the early part of King’s career. Readers still hold the collection in high regard and its continued popularity may be attributed to the many adaptations it spawned in addition to King’s reputation as a master of horror. Night Shift has been discussed ad nauseam in the decades since its initial publication, but commentary tends to focus on individual stories, overlooking the most remarkable element of the book: the overarching structure.

The structure King designed forms a collection in which stories function as individual movements of a horrifying symphony. Some stories had been previously published, some not, and they range from formulaic sci-fi/horror pulp to those with more widely acknowledged literary merit. But it is the positioning of the stories within the collection that demonstrates King’s facility for producing in the human psyche an unshakably disturbing experience.

The first four stories—“Jerusalem’s Lot,” “Graveyard Shift,” “Night Surf,” and “I Am the Doorway”—are together a collective reminder of the precedent set by King’s previous “vampire novel,” ‘Salem’s Lot. Smirk-worthy premises form the basis of each story: an old church houses the truth about the disappearance of a town’s residents, a clean-up crew encounters monstrous rats, the apocalypse arrives as a virus, and a former astronaut battles the after-effects of a close encounter. Like ‘Salem’s Lot, however, each premise yields a brief study of character over trope, suggesting that King intends to orchestrate more than cheap thrills. The stories that constitute the first quarter of the collection appropriate sci-fi and horror clichés only to subvert the reader’s expectations: each jolt depends less on sensational elements and more on King’s trademark grounding details to induce identification with the protagonists and their experiences.

If the first four stories persuade the reader to buy into the possibility of sci-fi/horror pulp as genuinely unsettling, then the next five test the reader more brazenly. To open the collection with the likes of “The Mangler” (an industrial ironing machine experiences demonic possession), “The Boogeyman” (a father watches his children die at the hands of, well, the boogeyman), or “Gray Matter” (an unappetizing beer is the catalyst for a man’s transformation into a blob-monster) would have perhaps set up the collection for a hefty dose of eye-rolling. But following the previous quartet, these stories demand to be taken seriously. Initiated by those early stories, King can coax his reader into a deeper understanding of the rest of the stories in this first half of the book, stories that could have been easily dismissed when considered individually. Within this context, a story like “The Boogeyman” becomes a tale of grappling with fatherhood, and the two remaining stories in this part of the book work in a similar fashion: “Battleground,” the story of a toy soldier onslaught, becomes childhood deconstructed, and “Trucks,” featuring angry motor vehicles, induces paranoia of technology and dependence. Together, the nine stories that populate the first half of the collection succeed in reinvigorating and recasting pulp.

It is at the book’s mid-point that things begin to shift. The early stories necessitate a credulity that horror fans happily adopt, making the first half of Night Shift quite satisfying; however, the stories that remain take full advantage of the newly minted expectations and shatter them. “Sometimes They Come Back” foreshadows the change in the atmosphere of the book by sitting both literally and thematically between sci-fi pulp and pulp-streaked psychological horror: a man haunted by his brother’s death is literally haunted years later by the boys responsible. This is the perfect combination of the human experience and recycled horror hallmarks. The reader returns to familiar footing when the “Sometimes” protagonist resorts to a supernatural solution to his problem; in reality, though, this is the first story to deal head-on with a universal conflict and marks a subtle shift away from genre into more fluid literary forms to explore what it means to be human. King proves he can do this with horror, and now he shows that he needs no crutch of form to repeat the effect, again and again.

The last half of Night Shift also grounds itself more firmly in reality than the first. Many stories are entirely possible if unlikely—a triviality when juxtaposed with aliens and boogeymen—some feature an unstable or otherwise unreliable narrator, and the most disturbing tales of all hardly wander beyond the realm of mainstream literary fiction. In stark contrast to the first half of the book, the very normalcy of the second set of stories proves unsettling. King earns the reader’s trust gradually, methodically, with the first nine stories, and then proceeds to masterfully undermine this trust. In “Strawberry Spring” a deceptive narrator recounts the work of a serial killer on campus: the ending is a shock, ideally, but not outside the realm of possibility; “The Ledge” recounts an unbearably tense story about the comeuppance of a cuckolded man seeking revenge; “The Lawnmower Man” is bizarre and nonsensical, but King leaves just enough uncertainty to question the narrator’s frame of mind; in “Quitters, Inc.” giving up smoking is literally torture but not quite supernatural; “I Know What You Need” ripples with voodoo but addresses belief over practice. King manipulates the frame to the point where the reader’s willing acceptance of the fantastic shifts to personal identification with the implausible.

By the final stories, it’s become difficult to look away; the collection builds tension as the stories mount, just as any good tale of horror. Whereas Night Shift’s first five stories are character-driven pulp, the final five bring the book full circle with another series of deeply disturbing character-focused stories. All along King has been luring the reader into the appropriate mindset to receive the concluding tales, which unflinchingly address the very subject matter sci-fi and horror often deal with obliquely, in metaphor and veil. Now that the reader is acclimated to the range of genre rules, King exposes exactly what one seeks to avoid by nestling in (arguably) escapist horror stories.

King ends Night Shift with the most “human” stories of the book. “Children of the Corn,” unlike the movie, describes a man struggling to salvage a troubled marriage who finds the limit of how far he will go to get his wife back. The narrator of “The Last Rung on the Ladder” copes with feelings of responsibility for his sister after she commits suicide. “The Man Who Loved Flowers” twists the theme of unlucky-in-love. While “One for the Road” forces a man to choose between his own well-being and his wife and daughter. King explores themes hardly specific to sci-fi and horror genre, and the tropes involved in each fictional world feel either incidental or coincidental.

Closing the collection is “The Woman in the Room,” which draws together the threads of all King’s orchestration, resulting in the most unsettling story in the book. The protagonist, John, visits his terminally ill mother in a nameless hospital and, with little alternative left, debates aiding her death. The mother’s deterioration creates a much greater sense of psychological dread than even euthanasia: “Her lips grip the straw in a way that reminds him of camels he has seen in travelogues.” She feels pain despite an inability to feel. Her misery unfolds on such a scale that that mere existence necessitates a reinterpretation of the passage of time. The horror lies in the inevitability and impotence involved in watching a loved-one suffer; the horror is that it directly confronts an issue that the genre often elides via the safely impossible. Even so, King refuses to concede a story devoid of mysterious elements: “His mother is paranoid about a great many things lately, and has once told him a man sometimes hides under her bed in the late-at-night,” but now the paranoia springs mercilessly from real-world phenomena—in this case pain medication.

Night Shift is finally an expert bait-and-switch by an author with an exceptional grasp of readers’ expectations, a profound understanding of the human psyche, and the ability to wield subtlety and control within genres customarily recognized for overkill. If his successes with Carrie, ‘Salem’s Lot, The Shining, and Rage drew the average reader into the world of horror, King’s first story collection shocks the horror aficionado back into an uncomfortable reality. In doing so, Night Shift achieves the ideal: a collection that is more than the sum of its parts. As early as 1978, Stephen King exploded preconceived notions of horror for newcomers and avid fans alike, and he continues to deliver on this thirty-five-year-old promise to disturb and unsettle readers everywhere.

Further Links and Resources:

- Read Jordan Millner’s review of King’s most recent book, Joyland.

- Read Shawn Andrew Mitchell’s recent review of Ben Percy’s horror/suspense novel, Red Moon.