When we were first dating, my wife sometimes commented on how I am too patient with strangers. Once, at a bar that she and I frequented in our twenties, an old man with a push-broom mustache sat down at our table, teetering drunk, and interrupted us mid-conversation to tell the story of a high school football game he’d played in decades before. It was a big game against a rival team and the story culminated with our guy punching one of the opposing players in the face. The old man described how he and the other player had crouched on opposite sides of the line of scrimmage, snarling at one another, waiting for the quarterback to hike the ball. Telling the story, he leaned across the high-top table like he was sharing a secret: “Hut…Hut…Hike!” And then he acted out his part, mimicking his past self. “You sonofabitch!” he growled, and he threw an uppercut into the air above our table. Then he rolled back on his stool, slapped his knee, and exploded into laughter. “You sonofabitch!” he cried again, and he repeated the whole gesture—uppercut, knee-slap, laughter.

The story was meant to impress us, but instead, it came off as a miserable display of masculine bravado. Still, I was fascinated. Why was this guy so proud of some dumb stunt he’d pulled forty or fifty years ago? My wife rolled her eyes and shifted uncomfortably. We tried to push the conversation in different directions, but the old man refused to let it go, kept circling back, repeating abbreviated versions of the story two or three more times in that one sitting. I imagine everyone at the bar must have heard it at some point, and here he was, telling it again, and again, forcing this one small triumph upon anyone who would listen, which, to my wife’s chagrin, included me, sitting on the edge of my stool, nodding politely, happily indulging the old man’s pitiful reminiscence. Obtrusive as it was, I couldn’t help but feel engaged in the strange drama that was unfolding before us.

I have the same trouble with door-to-door canvassers and people who ask for change at the bus stop. I let them recite their script, let them get through their whole story before I empty my pockets or tell them I’m not interested. Sometimes I tell myself I’m just being polite. Other times, I try to convince myself it’s in service of my writing, that I’m plucking details or absorbing the cadence of their voices. Who knows. Maybe I just like being told a story, no matter how mundane. I like observing the strange behavior of other humans, and I like to feel that little tug of something—that shifting of feathers in my heart—when I notice a drama unfolding, even if it’s not whatever drama the stranger thinks they’re telling me about.

A few summers ago, I was at the Community of Writers conference in Olympic Valley, California, and I found myself thinking about that old man at the bar. I was listening to a panel discussion on constructing plot in fiction. Among the panelists was the writer Victoria Patterson, who at one point described a particular species of story that she dubbed “Weird Harold stories.” I’m paraphrasing, but as Patterson explained, Weird Harold stories are stories in which the narrator is passive, uninvolved in the plot, functioning mostly as an observer who relays information to the reader rather than a participant in the story’s action.

Patterson didn’t cite the origin of the phrase in her talk, though it seems likely an allusion to the Fat Albert character Weird Harold, who was a peripheral character on the old animated television series. Patterson did, however, credit learning the phrase from one of her teachers at UC Riverside, Michael Jaime-Becerra, who, in a recent email correspondence, told me that he picked it up in turn from an essay he read when he was a grad student. With a bit further digging, the phrase seems to have been first introduced (in this context, at least) by Jerome Stern in an essay from his book Making Shapely Fiction. Yet while Stern’s definition emphasizes a lack of character development (he writes that “Weird Harolds are stories focused on a character who is strange and different,” and that “readers are given many examples of the character’s behavior, but no insight into the character”), Patterson’s version had evolved slightly, shifting the point of view, introducing a peripheral narrator—someone who is standing on the sidelines, watching some other character, and thinking, “Boy, that guy sure is weird.”

In American literature, The Great Gatsby is probably the most obvious example of a Weird Harold story. Fitzgerald’s narrator, Nick Carraway, hardly has anything to do with the novel’s plot-action; he spends most of the story just marveling at Gatsby’s extravagant life and quietly observing as Gatsby, Daisy, and Tom careen toward their own tragic ends. Love triangles, deception, revenge—all manner of boozy drama swirls through Gatsby’s plot-action, but Nick is scarcely involved in any of it.

In American literature, The Great Gatsby is probably the most obvious example of a Weird Harold story. Fitzgerald’s narrator, Nick Carraway, hardly has anything to do with the novel’s plot-action; he spends most of the story just marveling at Gatsby’s extravagant life and quietly observing as Gatsby, Daisy, and Tom careen toward their own tragic ends. Love triangles, deception, revenge—all manner of boozy drama swirls through Gatsby’s plot-action, but Nick is scarcely involved in any of it.

To explicate on Patterson’s (and Stern’s) definition, I think it’s this relationship between peripheral narrator (Nick Carraway) and focal character (Jay Gatsby) that defines the style of story. Like Nick, the peripheral narrator is just that—peripheral, passive, uninvolved in the primary plot or conflict—whereas the focal character, like Gatsby, is the one who moves through most of the plot-action and who bears the weight of whatever drama unfolds.

Regarding the old man at the bar, I couldn’t help but identify with the sort of peripheral narrator that Patterson described: in whatever story the old man and I belonged to, I was the silent observer, and the old man was my focal character. He is the one who the action and drama are centered on: here he is, shuffling from table to table, unloading his story on unwitting strangers, utterly obsessed with this one memory from decades past—obsessed with some better version of himself that he clings to as he sinks into old age and alcoholism. And me—the narrator—I’m just listening, watching him move through the scene, mostly uninvolved, but fascinated enough to want to relay the events to you, the reader.

We writers often balk at the idea of a narrator who doesn’t seem to matter to the story, and justifiably so. There are inevitably questions about motivation and what’s at stake. And yet, I can’t help but feel like these are exactly the types of stories that play out again and again in my daily life. And when these stories occur—both in life and in fiction—there can be an almost a ghostly quality that arises: like Nick Carraway, we can feel ourselves being moved by something completely beyond our experience.

One of my favorite stories is this genre is “Neighborhood Drunk,” by Stuart Dybek. In Dybek’s story, an unnamed narrator observes Sterndorf—the focal character—an alcoholic living in a basement apartment in their Polish Chicago neighborhood. Sterndorf’s gradual self-destruction plays out in the story’s foreground over the years it takes for the narrator to grow from a young child to a teenager. Without much involvement on the narrator’s part, the bulk of “Neighborhood Drunk” is focused on simply describing Sterndorf’s character—his habits and eccentricities and the small ways in which his life brushes against those of other people in the neighborhood. Much of the story exists in expository passages that indulge in pure portraiture:

Sometimes he’d do something crazy like wrapping himself up in the funnies section of the Sunday paper and going to sleep in the middle of California Avenue during rush hour. The cops would come and haul him away. Another time the hook and ladder had to come and get him down from the high-voltage wires at the top of an electric pole where he’d spent the day drinking, swearing, and spitting down on whoever stopped below.

They never locked him up for long. In a week he’d usually reappear, looking cleaned up, talking with the neighborhood men in the evenings as they drank their beer and watered their small lawns.

The only job he had was mopping up in various neighborhood taverns. He didn’t need much. The Army sent him a check and he lived with his mother in a small house she owned on Luther Street.

These sorts of expository passages are arranged around loose bits of plot-action: Sterndorf plays baseball with the neighborhood kids; later, he is badly injured in a motorcycle accident; and eventually, Sterndorf buys a bottle of liquor for the narrator and his teenage friends. But all of these scenes feel more like snapshot vignettes of Sterndorf’s character rather than plot points moving the story forward. Thus, the story becomes doubly challenging: not only do we have a passive, peripheral narrator, but we also don’t have much in the way of tension, conflict, or forward plot movement.

Nevertheless, as a reader, I still feel compelled by Sterndorf’s plight. Like Sterndorf, the focal characters in these stories are often outcasts, misfits, deviants—people about whom narrators can enjoy a sort of gossipy voyeurism. Or, as with Gatsby, they might be people in possession of dramatic personalities and fantastic circumstances. In Gatsby, readers put up with Nick’s peripheral involvement because, like him, our curiosity is piqued by this mysterious millionaire who lives next door. We are able to withstand the passivity of the narrator and the lack of forward plot movement in “Neighborhood Drunk” at least in part because Sterndorf’s character is so richly portrayed and because we delight in simply watching this sad, funny, cartoonish man.

Nevertheless, as a reader, I still feel compelled by Sterndorf’s plight. Like Sterndorf, the focal characters in these stories are often outcasts, misfits, deviants—people about whom narrators can enjoy a sort of gossipy voyeurism. Or, as with Gatsby, they might be people in possession of dramatic personalities and fantastic circumstances. In Gatsby, readers put up with Nick’s peripheral involvement because, like him, our curiosity is piqued by this mysterious millionaire who lives next door. We are able to withstand the passivity of the narrator and the lack of forward plot movement in “Neighborhood Drunk” at least in part because Sterndorf’s character is so richly portrayed and because we delight in simply watching this sad, funny, cartoonish man.

Amplifying the tension between actor and observer, while focal characters like Gatsby and Sterndorf are often misfits of some sort, the peripheral narrators of these stories are often outsiders—perhaps this is even mandated in the fact of their peripherality. For example, Nick Carraway, at the start of Gatsby, is the new guy in town, a Midwesterner who has only recently moved to Long Island. His lifestyle—his values, his experiences—is vastly different from that of every other character in the story. At the end of the novel, Nick leaves New York, disgusted by what he’s seen during his brief time among the East Coast socialites, and returns to the Midwest. Nick is peripheral not only to the action and drama, but to the social world of the story, as well.

The narrator of “Neighborhood Drunk” isn’t quite as literally positioned as an outsider—he’s one of countless neighborhood kids populating the world of the story. But there’s still a sense of separation or detachment that comes through in his voice: he tells much of the story from a first-person-plural point of view (“we” rather than “I”) so that his voice blends with that of the larger community, emphasizing the sense that, with regards to Sterndorf, he is scarcely more than a rubbernecker driving past an accident.

Charles Baxter, in his essay “Counterpointed Characterization,” argues that “we seem to know ourselves only by comparing ourselves to someone else, to others. We knit together what comparative context we can,” he writes. “In day-to-day life, we play these little games of comparison-contrast in which we are usually the contrast.” This might explain the sort of outsider-outsider relationship of narrator to focal character in these particular types of stories. Usually, the peripheral narrator spends time observing the focal character precisely because of the contrast between them, but it’s a movement between these modes of contrast and comparison—the shift from observing difference to recognizing commonality, or vice versa—that usually provides the movement necessary to engage the narrator in whatever drama the focal character is wrapped up in. “Neighborhood Drunk,” for example, is, on its surface, a story about an alcoholic’s tragic decline. But there’s an understory lingering beneath that surface, a more subtle arc that is built through the narrator’s observation of that decline. This arc emerges only in the last few pages, when, as a teenager, drunk with his friends, the narrator encounters Sterndorf—by way of comparison—as a sort of grim shadow of his own possible future. Baxter elaborates: “By telling stories in this manner, we become narratable. We find a story for ourselves. We spin around ourselves, in what seems to be a natural form, the cobweb of a plot. We move our own lives into the condition of narrative progression.” In all of the attention that Dybek’s narrator gives to Sterndorf, we inevitably come to learn something of how the narrator sees himself. We inevitably move through those modes of comparison and contrast and come to settle on some understanding of the meaning—the ghost of likeness—that exists between the two characters.

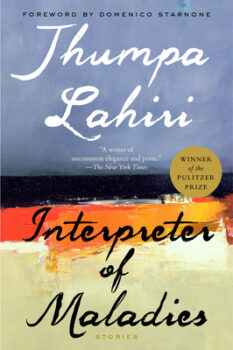

The nature of the relationship between peripheral narrator and focal character is perhaps best exemplified in Jhumpa Lahiri’s story “When Mr. Pirzada Came to Dine.” Lahiri’s narrator tells of the brief time during her childhood when her parents’ befriended Mr. Pirzada—a Bengalese Muslim who was a visiting researcher at the New England university where the narrator’s father works. The story is set in 1971, during the Indo-Pakistan Civil War, and Dacca, the city where Mr. Pirzada is from, is the frontline of the battle for Bengalese independence. The narrator’s parents are both Indian Hindus and because they live in a small, isolated campus, and because Mr. Pirzada is “familiar to their part of the world,” the narrator’s parents begin a routine of inviting him to dinner each evening.

Much of the narrator’s fascination with Mr. Pirzada comes from her struggle to understand the cultural similarities and geo-political divisions between him and her parents. “Mr. Pirzada is no longer considered Indian,” her father tells her. “Dacca no longer belongs to us.” The narrator goes on to explain:

It made no sense to me. Mr. Pirzada and my parents spoke the same language, laughed at the same jokes, looked more or less the same. They ate pickled mangoes with their meals, ate rice every night for supper with their hands. Like my parents, Mr. Pirzada took off his shoes before entering a room, chewed fennel seeds after meals as a digestive, drank no alcohol, for dessert dipped austere biscuits into successive cups of tea. Nevertheless my father insisted that I understand the difference, and he led me to a map of the world taped to the wall over his desk.

Lahiri’s narrator is constantly moving through those different modes of comparison and contrast. “I began to study him with extra care,” she says, “to try to figure out what made him different.”

As with “Neighborhood Drunk,” Lahiri’s story doesn’t have much in the way of plot-action: The narrator accepts gifts of candy from Mr. Pirzada and they carve pumpkins together at Halloween. Over dinner each night, Mr. Pirzada and the narrator’s father sit down to watch television and catch any news of the war in Pakistan. Early in the story, the narrator learns that Mr. Pirzada has a wife and seven daughters who still live in Dacca and who, for the past six months, he has been unable to contact. Thus, Mr. Pirzada is stuck in a sort of geographic purgatory: he knows nothing of his family’s safety and is unable to do much beyond following the news and hoping for the best. She notes the watch that Mr. Pirzada is constantly taking from his breast pocket and re-winding; his life, she realizes, “was being lived in Dacca first […] Our meals, our actions, were only a shadow of what had already happened there, a lagging ghost of where Mr. Pirzada really belonged.”

In spite of Mr. Pirzada’s inner turmoil, his outward appearance is rarely anything but charming. He is always impeccably dressed in beautifully tailored suits and a carefully fastened fez; he makes a formal ritual of bringing gifts of candy to the narrator each night when he visits (“for the lady of the house”); and his manners are almost affectedly polite. “He was not my notion of a man burdened by such grave concerns,” the narrator explains. All of this makes Mr. Pirzada doubly helpless: not only is he geographically separated from his family and uncertain of their safety, but he is also unable to bring himself to speak of these worries, unable to burden the narrator’s family in even the slightest way.

And because she is so peripheral to Mr. Pirzada’s conflict, Lahiri’s narrator is equally helpless. Even though her family is very close to Mr. Pirzada and she is able to recognize the man’s quiet anguish, she herself is only ten years old. She doesn’t fully understand the political situation that has imperiled Mr. Pirzada’s family, and even if she could, she is always distracted by homework while Mr. Pirzada and her father are sitting down to watch the news. Furthermore, unlike her parents, who share some geo-cultural touchstones with Mr. Pirzada, the narrator has grown up entirely in the United States. She is altogether ill-equipped to console this adult man who comes from a completely different part of the world. The best she can do is save his gifts of candy for when she goes to bed and then hold them in her mouth—a small and private ritual that she performs as a sort of prayer for Mr. Pirzada’s family. In her helplessness, the narrator even begins to take on some of Mr. Pirzada’s demureness. When the narrator’s friend from school asks her about Mr. Pirzada, she replies, “His daughters are missing,” only to then quickly redress the comment: “As soon as I said it, I wished I had not. I felt that my saying it made it true, that Mr. Pirzada’s daughters really were missing, and that he would never see them again […] ‘I didn’t mean they were missing,’” she tells her friend. “‘I meant, he misses them.’”

And because she is so peripheral to Mr. Pirzada’s conflict, Lahiri’s narrator is equally helpless. Even though her family is very close to Mr. Pirzada and she is able to recognize the man’s quiet anguish, she herself is only ten years old. She doesn’t fully understand the political situation that has imperiled Mr. Pirzada’s family, and even if she could, she is always distracted by homework while Mr. Pirzada and her father are sitting down to watch the news. Furthermore, unlike her parents, who share some geo-cultural touchstones with Mr. Pirzada, the narrator has grown up entirely in the United States. She is altogether ill-equipped to console this adult man who comes from a completely different part of the world. The best she can do is save his gifts of candy for when she goes to bed and then hold them in her mouth—a small and private ritual that she performs as a sort of prayer for Mr. Pirzada’s family. In her helplessness, the narrator even begins to take on some of Mr. Pirzada’s demureness. When the narrator’s friend from school asks her about Mr. Pirzada, she replies, “His daughters are missing,” only to then quickly redress the comment: “As soon as I said it, I wished I had not. I felt that my saying it made it true, that Mr. Pirzada’s daughters really were missing, and that he would never see them again […] ‘I didn’t mean they were missing,’” she tells her friend. “‘I meant, he misses them.’”

For Mr. Pirzada, the stakes are clear enough, but the conflict for Lahiri’s narrator is murkier, something beyond the realm of plot-action. Rather than any sort of urgent obstacle, Lahiri’s narrator faces a more subtle, abstract problem: being helpless to another person’s suffering. Her entire conflict might be expressed as the question of how to solve a problem that doesn’t belong to her. And this might be, I think, a question that lives at the heart of all of these stories: no matter how uninvolved a peripheral narrator might be, they must on some level absorb the conflicts of their focal character, and they must be changed by the pain they witness in another person.

More important, perhaps, these narrators must continue to grow or be changed because of the experience. In the final paragraphs, months after Mr. Pirzada has left them and returned to Dacca, the narrator’s family receives a letter from him in which he thanks them for their hospitality. “Though I had not seen him for months,” the narrator explains, “it was only then that I felt Mr. Pirzada’s absence. It was only then […] that I knew what it meant to miss someone who was so many miles and hours away, just as he had missed his wife and daughters for so many months.”

No matter where the narrator lands in this shift, these stories prove listening and observing to be exercises in humanity and show how there is transformative power in simply recognizing another person’s trouble, even if that person is as unsavory as Sterndorf, as misguided as Gatsby, as affected as Pirzada, or, say, as tiresome as an old drunk insisting that you listen to his story about a high school football game from decades ago. Even if they are peripheral to the drama of the focal character’s action, an observant narrator can watch and listen and wonder just how many other poor saps that old man has tortured with this story. They can watch the neon bar lights shining off the man’s bald head, and as they sit, passively observing, maybe they get the sense that this one moment, this high school football game from decades ago—probably long forgotten by any of the other people who stood in the crowd or played on the field that day—had somehow been the high point of the man’s life. They can get the sense that, for whatever reason, everything has been mostly downhill since then. And maybe the narrator can’t quite articulate what it is that they feel in that moment—some combination of sadness, aggravation, and amusement—but they might find themselves, months or even years later, having come home from a beer too many at that same bar, sitting awake in the dark, feeling almost haunted by the man. Or, the narrator might shake their head remembering the old man’s stupid story only to find themselves wondering, as they drift toward sleep, what the corollary moments of their own life might be—what small, beautiful joys they might hold onto, crystallized in memory, that they just can’t wait to share with whatever stranger would listen.