I.

“To the extent that the establishment depends on the inarticulacy of the governed, good writing is inherently subversive.”

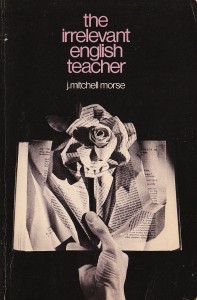

Published in 1972, J. Mitchell Morse’s The Irrelevant English Teacher opens with this assertion—which, for all its clarity and force, rings with an earnestness that may sound tinny to the modern ear. These days, after all, many wonderful novels fail to produce even a blip on the cultural radar, unless a talk-show host uses them as tools to expand her media empire. Remarkable collections of short stories and poetry vanish in a conspiratorial hush, like Argentine dissidents. In classrooms across the country, many students respond to what Morse would call “good writing” with distaste or—worse—indifference. And Morse’s books themselves are dust-gatherers, long out of print.

So our first response to The Irrelevant English Teacher may be a wan smile. Does the FBI keep a secret file on Richard Ford, known agitator? Does Sarah Palin lay awake at night, worrying that some literary pusher will offer little Bristol a taste of Lorrie Moore?

Well, perhaps they should.

Over the course of eleven essays and 140 pages, Morse backs up his starry-eyed claim. Writing well, he subverts the norms of his own era—the smug Philistinism of Nixon and Agnew, the incipient political correctness of the universities, the crude anger and lotus-eating blitheness of the fading Sixties—while offering you and me, nearly forty years later, a valuable reminder: we are irrelevant, and irrelevancy makes us dangerous.

II.

During the election season especially, it’s easy to lose sight of the irrelevant. Every time we open a newspaper or tune to CNN, we are bombarded by relevancy, and many everyday acts—filling up at the Texaco station or scribbling a check for health insurance (or a mortgage, or student loans)—have become darkly symbolic, fraught with ominous meaning.

In this context, a love of literature might seem vestigial, escapist. Moby-Dick won’t feed the Darfur orphans; Anna Karenina won’t hasten ratification of the Kyoto Protocol. These books merely delight us, nothing more.

But Morse argues that there is nothing mere about delight. It’s true that literature alone “can’t feed us, it can’t solve the problems of poverty and injustice, it can’t bring peace or clean air or drinkable water,” and yet “we must not turn our backs on art because it is less important than food or because its action is no stronger than a flower.”

Like a flower, literature is significant for the joy it brings us. And the joy that literature brings us is special: we are transformed by it. As Morse puts it:

“Joy is a value we undervalue at our political peril. Once we have experienced joy, we are much less satisfied with dullness; once we have joined in the joyful play of a lively mind, we are much less easily impressed by the stencils and stereotypes of a Presidential commercial.”

III.

“Stencils and stereotypes”: emerging from the deep fictional dream engendered by an Atonement or a “Daughters of the Late Colonel” and turning directly to CNN’s coverage of a presidential debate (complete with live tracking of audience reactions so that we know exactly how to feel) or this month’s issue of Lucky (or Newsweek, Rolling Stone, Sports Illustrated) is like reentering Plato’s cave after spending an hour in the light. The lover of literature’s refined capacity for joy provides a form of intellectual armor. Delighted by “Ripeness is all,” she is girded against the cheap tricks of advertisement and demagoguery—”The original mavericks!” or “Yes we can!” or “Coke is it!”

In an essay titled “Social Relevance, Literary Judgment, and the New Right,” Morse offers this description of the transformative power of literature:

“I . . . believe in the development of a critical, skeptical, humorous habit of mind—in the development of a liberally educated consciousness, a sensitivity to nuances and unstated implications, an ability to read between the lines and to hear undertones and overtones—both for the sake of political and social enlightenment and for the sake of our personal enlightenment and pleasure as individuals.”

Exposure to good writing raises our standards for all discourse. We lose patience with claptrap and grow resistant to hypnotism. We begin to think for ourselves. Confronted, in one of Morse’s examples, by the bathetic sentimentality of many pop songs, our response is likely to be contrarian. “If a lyric offers nothing for our intellect to perceive but the fact that it is making a cliché appeal to our tears, we will respond not with tears but with a smile of amusement or a sigh of boredom or a moment of resentment at the effort to take us in.”

IV.

There are words for those who sigh with boredom and frown with resentment. The catch-all label currently being bandied about is “elitist.” In Morse’s own era, the same attitude was neatly encapsulated by Spiro Agnew’s spitting disdain for “the nattering nabobs of negativity,” that “effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals.”

Yes, I say, guilty as charged. Why fight it? Why hide our copy of A Curtain of Green under the table while we scramble to remind our accusers that our father grew up in the blue-collar steel town of Scranton? We are negative, after all—there’s just so much, these days, to be negative about, so much that falls short of the intellectual and moral standards set by good writing. And surely, to some, that negativity must seem impudent in its consistent failure to show due deference to our political and cultural authorities.

But it’s Agnew’s use of the word corps that I’m most eager to bend to my own purposes. I love the martial connotation, the way it recruits those impudent intellectuals into a paramilitary outfit. An elite outfit. It makes me wonder how much difference there could have been, in Agnew’s mind, between a lover of literature, acutely aware of—and articulately calling attention to—the hypocrisy and shallowness in her own society, and a bomb-throwing radical from the fringes of the counterculture.

Morse, as always, puts it simply: writing, and partaking of good writing, “is a fundamental revolutionary activity that changes our ways of thinking and feeling.” In the “pleasures of well-made language” lie “the deep springs of originality and hence of unorthodoxy.”

V.

Neither Agnew nor Morse is the first to link good writing with subversion, of course. Consider Plato again, who banished poetry from his ideal republic. Or Isaac Babel, who, in his story “Guy de Maupassant,” wrote: “I began to speak of style, of the army of words, of the army in which all kinds of weapons may come into play. No iron can stab the heart with such force as a period put just at the right place.” Later, the twenty-nine volumes of Maupassant’s collected works are described as “twenty-nine bombs stuffed with pity, genius, and passion.”

Armies, stabbing iron, bombs: I don’t believe I’m overstating my case, or Morse’s, when I note that typing a word requires many of the same small muscles as pulling a trigger.

Isaac Babel was himself dangerous, a countercultural radical engaged in a fundamental revolutionary activity. Why else did Stalin’s regime incarcerate and torture him? Why else starve him and erase his identity? Why else put a bullet through his head?

Among the charges leveled against him was “aestheticism”—in other words, irrelevancy. Babel’s stories, sketches, and screenplays didn’t lionize the Soviet government, celebrate its values, or impugn its enemies, and in so failing, they revealed their author’s impudence. In the face of greater, more relevant demands, he was out to delight his readers, nothing more.

VI.

I’ll end at the beginning.

I owe my discovery of J. Mitchell Morse to Wyatt Mason, contributing editor at Harper’s, who in a blog entry described Morse’s books as “serious, funny, learned, angry, angering,” and Morse himself as “a literate man hell-bent on good usage and not unwilling to offend while making his campaign.” How could I resist an endorsement like that? And as an adjunct instructor of college composition, how could I resist a title like The Irrelevant English Teacher?

I tracked down a copy on the Internet. The spine had never been cracked.

We must write well and read well, Morse insists—but more than this, we must cultivate these abilities in others. We must encourage more people to crack the spines of more books. “Thus far,” chides Morse, “we have failed . . . inasmuch as we have been too timid or too politic or too disdainful to answer the demagogues who call the liberating arts ‘the bullshit subjicks’.” On some level, consciously or not, we’ve equated irrelevancy with frivolity; we’ve forgotten what a serious thing literary joy can be, and how necessary. We need to remember this—and if others deny it, we must learn to insist.

“The liberating arts,” though: I like that. Again I’m reminded of Isaac Babel, who did not take the task of spreading joy lightly. His last words were, “I am asking for one thing—let me finish my work.”

When J. Mitchell Morse calls readers, writers, and teachers of the English language “irrelevant,” he is voicing not a lament, but a manifesto. Let’s embrace our irrelevancy. Let’s all finish our work.