Editor’s Note: As we approach our tenth year of publishing Fiction Writers Review, we’ve decided to curate a series of “From the Archives” posts that we’ll re-publish each week or so during 2017. Some of these features are editor favorites, some tie in with a new book out from an author whose worked we’ve covered in the past, and some are first conversations with debut authors who are now household names.

This week we’ve returned to Rebecca Scherm’s interview with Elizabeth McCracken and V.V. Ganeshananthan, which was originally published on March 4 of 2013.

I recently learned the term grand-adviser from a friend, excited to relate herself to her intellectual idols. Your grand-adviser is your adviser’s adviser, your teacher’s teacher. Discovering your grand-adviser seems like an elegant way, especially for writers, to trace influence—not to mention an association with our heroes, who seem especially grand when we’re just starting out.

When Elizabeth McCracken visited the University of Michigan this February [of 2013] as a guest of the Zell Visiting Writers Series, she sat down with me and V.V. (Sugi) Ganeshananthan, one of McCracken’s former students and also one of my teachers. This was something of a dream interview for me, as an admirer of both writers’ work. But there was something more: in asking your teachers to talk about their teachers, you see a precious glimpse of them as students—searching, uncertain, loyal to their heroes, and grateful for their heroes’ attention. With great relief, you see a little of yourself in those you admire.

V.V. Ganeshananthan is the author of Love Marriage, long-listed for the Orange Prize and named one of Washington Post Book World’s Best of 2008. Her work has appeared in Granta, The Atlantic Monthly, The Washington Post, Columbia Journalism Review, Sepia Mutiny, Himal Southasian, and The American Prospect, among others.

McCracken is the author of five books: Thunderstruck & Other Stories; Here’s Your Hat What’s Your Hurry; The Giant’s House, a finalist for a National Book Award; Niagara Falls All Over Again, winner of the L.L. Winship /PEN New England award; and the memoir An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination. She is a former public librarian, and she now holds the James Michener Chair in Fiction at the University of Texas at Austin. She has won many grants and awards, including those from the National Endowment for the Arts, the American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Guggenheim Foundation.

Interview

Rebecca Scherm: First, how do you two know each other?

McCracken: I met Sugi when she was an undergraduate [at Harvard] and I came for a two-day visiting writer workshop. And then, in 2003, Sugi came to Iowa, where she was in my graduate workshop.

Ganeshananthan: Recently, I found a critique you wrote for me as an undergrad. It was about comic fiction—how to time your jokes, encouraging me not to crack jokes that weren’t seated in any particular action.

When I met you, I’d read everything you’d written up to that point because of Jan Bowman, my high school English teacher. She gave me your entire body of work and most of Michael Ondaatje, and all of that writing has been extremely influential to me as a writer. Those books are the ones I like to have near my desk, wherever I live.

Elizabeth, did you have such a teacher? Someone who gave you things to read that influenced your writing, or even the fact that you started writing at all?

Elizabeth, did you have such a teacher? Someone who gave you things to read that influenced your writing, or even the fact that you started writing at all?

McCracken: In high school, I was such an indifferent student. My teachers were just trying to get me to do my work at all. In college, I had Derek Walcott for playwriting. I was a terrible playwright, but anything I know about structure, and a lot about character development, is from trying to write plays for so long. I had George Starbuck for poetry and Sue Miller as a fiction teacher, just before her first book, The Good Mother, came out and was a huge success. Interestingly, I had Allan Gurganus just before Oldest Living Confederate Widow Tells All came out, so I think I had a quite demented idea of what happened to all first books!

I was just thinking about Sue recently—she read a Grace Paley story, “Once,” out loud to us. She was a wonderful reader. A year later, Allan Gurganus read “Conversations with my Father” to us. Sugi, do you read to your graduate students?

Ganeshananthan: I do it more now, because I love when other people read aloud. I have a tendency to talk about the big-picture in workshop, structure, and forget the sentence. Reading work out loud forces me to slow down for the sentence.

Sugi introduced me to your work, Elizabeth, through your story “It’s Bad Luck to Die,” and then I read your novels and collection. So there’s a chain of influence here, both in teaching relationships and also in the work itself. Elizabeth, who would you add to this chain?

McCracken: I had Allan Gurganus at the right moment. I went to graduate school right out of college, which I advise my students against, and I went to Iowa for fiction because they offered me some sketchy financial aid. I had been writing poetry and fiction, but in Allan’s fiction class, I had a conversion. If he had been a modern dancer, I would probably be a modern dancer now. Whatever he told us was the best work in the world, I would have done, and he told us fiction was the best work in the world. On the first day—and I do this now, when I teach—he said we were all writers, and to worry about identity was quite boring.

He was both evangelical and rigorous about fiction—kind, but exacting. And I feel so lucky that I landed in that class. He came to Austin about a year ago. My son was four, and into Robin Hood. Allan Gurganus played Little John. Strangely enough, that’s about Allan as a human being and a teacher and a writer—he has the ability to connect to people, both on his terms and on their terms.

He was both evangelical and rigorous about fiction—kind, but exacting. And I feel so lucky that I landed in that class. He came to Austin about a year ago. My son was four, and into Robin Hood. Allan Gurganus played Little John. Strangely enough, that’s about Allan as a human being and a teacher and a writer—he has the ability to connect to people, both on his terms and on their terms.

Do you still hear him, when you’re working?

McCracken: Yes. I hear him when I write, a lot when I teach. And when I read Grace Paley’s “Conversations with my Father,” one of my very favorite stories, I still hear it in Allan’s voice. That was twenty-five years ago.

And since Allan was taught by John Cheever, that makes Cheever my grand-adviser.

Does teaching give you anything as a writer?

McCracken: I love teaching. Right now, I’m reading admissions applications, supervising eight graduate theses, and running a workshop. It’s a time of intense reading, but even when I’m moaning, there is something exciting about all this. You read all these stories and then you get to one sentence and think, “I want to work with you.” And I love doing thesis work, and seeing both the transformation of work written two years ago and what they’re working on now. My favorite thing is sitting in my office and talking with graduate students about their work.

That said, the problem with teaching is that it takes up the same mental real estate that writing does. Graduate students, by and large, are so grateful for your time, especially if you’re sitting with them and talking about their work. They are gratifying people to teach. And there’s a balance a writer needs to find of not seeking that short-term gratification constantly.

Is there teaching advice you find yourself wanting to give often, or even to everyone?

McCracken: No. There is nothing that’s applicable to everyone’s work, only habits of work. On the first of class, I always say, “People ask if creative writing can be taught. My feeling is no.” And I keep waiting for people to laugh, but they write it down very seriously.

Ganeshananthan: Oh, I bet I did!

McCracken: I feel so strongly that every rule of fiction is a way to prevent writers from making mistakes. And mistakes are literature. Bad habits are what make writers individual. I think I could take a classroom of people who like literature but are not particularly talented or ambitious—clearly this is an idea for a reality show—and teach them each to write a really serviceable story with no mistakes in it. But that sounds horrible.

What graduate school, particularly, is for, is for students to figure out how to write their own stories. Every story in the world has its own rules, peculiar to that story. I don’t know what they are—only the writer does. That’s why I believe in the workshop process. Craft is entirely renovation. Do you guys think about craft when you write?

Ganesthanthan: If I do, it generally indicates a big problem.

When new students ask me if I became a better writer here, I say no, I didn’t, but I became a much better reviser. That’s craft, to me. Sugi, what advice do you find yourself repeating as a teacher?

Ganesthananthan: I think all my students have heard me say, “Each story teaches you how to read it,” which is taken directly from Elizabeth. As teachers, we become these little amalgamations of our own teachers. I quote my teachers a lot. My friend Yiyun Li and I were talking about all these writing teachers around the country saying “meaning, sense, and clarity,” which is from Frank Conroy. He probably has great-great-grand-advisees who quote him and don’t even know it.

is taken directly from Elizabeth. As teachers, we become these little amalgamations of our own teachers. I quote my teachers a lot. My friend Yiyun Li and I were talking about all these writing teachers around the country saying “meaning, sense, and clarity,” which is from Frank Conroy. He probably has great-great-grand-advisees who quote him and don’t even know it.

The longer I teach, the more I say that the mistakes in the story are the things we love. My students know I love Junot Diaz, and when we get to the chapter in The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao where we’re suddenly in Lola’s point of view, my students want to know why. And I have to say I don’t care! I just want to read on! I don’t want to talk about it as “getting away with something” because that sounds like tolerating it, when really we’re celebrating it.

That is familiar to me, Sugi. You have coached me to make the messy choice when I was afraid to, when I wanted to make the “correct” choice. And in teaching me that, you’ve also taught me to believe that I am the authority of my writing, of its rules.

Ganesthananthan: I do a lot of what other people call “prescriptive” suggesting, not to be prescriptive, but so we have specifics to talk about. Well, if the character makes this bad choice, what does that do to everything else? And if she doesn’t do it, why?

McCracken: Even in a perfect workshop, you’re not going to be able to apply more than twenty percent of the advice you get to your story. Prescriptive advice should be given in that spirit. At the same time, it’s exciting for someone to say, “I have entered the world of your story enough that I want different things to happen in it.”

Do readers ever bring things to your work that you find intrusive, or are their ideas about your themes and intentions always welcome or illuminating in some way?

McCracken: It’s strange to hear people talking about your work and finding meaning in you didn’t think you’d put there. I had a student ask me recently why so many people cut their hair in my work.

This is something else I always tell my students who are publishing their first work and feeling vulnerable or exposed. It’s a river you cross once. There are things in the writing life you have to do over and over again: if you always get mired in plot, you’ll have to fight your way through plot all the time. If you always lose confidence two-thirds of the way through the book, you’re not going to become so proficient that you never lose confidence. But that fear of being exposed by your work is a river you cross once. So it’s not disconcerting for people to find new meaning in your work, it’s just interesting.

The last story in Here’s Your Hat What’s Your Hurry is about a murderer who killed his wife and child in the early 30s. It was based on this man who worked for my grandparents. He lived in a halfway house, and my grandparents hired the men who lived there to do work around the house. My story references the fact that when he was let out of jail, he attacked his parole officer with a utility knife.

I got an email from the parole officer. I wrote that story more than twenty years ago, and a friend of his kid was reading the story and said, “Wait a minute—I think I know who this story is about.” This man wrote the whole story out for me from his point of view. The attack on the parole officer is just one sentence in my story, but I had imagined a little man attacking a big, tough guy. It turns out, the murderer was 6’6” and weighed 230 pounds. The parole officer weighed 120 and was really badly hurt. I thought he’d only been sliced up a bit, but he needed 380 stitches. This guy wasn’t complaining. He wasn’t saying I’d got it all wrong. He just thought I’d be interested, and I was.

When you write fiction that is even mildly based on real people, you’ll hear from them. I’ve written about public figures and gotten letters telling me I got it right and others that say they can’t believe I ripped off that story. But that, too, is a river that you cross once.

When you write fiction that is even mildly based on real people, you’ll hear from them. I’ve written about public figures and gotten letters telling me I got it right and others that say they can’t believe I ripped off that story. But that, too, is a river that you cross once.

And all in one sentence of a short story! Your stories have the same scale and grandness—birth, death, very long spans of time—that your novels do. I’ve wanted to ask you this for ages: how is such a big story born in a small space?

McCracken: It’s a disappointing answer. I’m terrible at plot. I’ve gotten better. In my two novels, someone is born, and somebody dies. I have this theory of plot that’s based on my friend Ann Patchett. Her work is very plot-based, and she had a childhood full of event. My childhood was interesting because it was full of peculiar characters. But as I’ve gotten older, and things have happened in my life, I’ve begun to understand event in a different way. My stories have different plots than they used to, because the way I think about event is different.

The way the rhythm of your life changes will change the rhythm of your fiction.

McCracken: Oh, yeah. It’s easy to think you’ll always be the same kind of writer, and I don’t think that’s true. You won’t necessarily improve, but you will change.

This is Sugi’s question for you: What is a book you wish you had written? Or a book you love that maybe inspires a bite of envy?

McCracken: That’s really two separate questions. Do you choose something you think you might be capable of writing, or something completely different from what you do? Do I want to have written Lush Life by Richard Price, a book that is so far from my abilities that I would have had to have been a different person to write it?

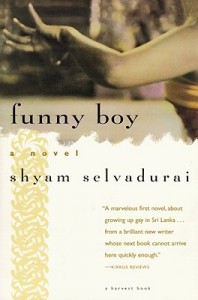

Ganeshananthan: I was in Sri Lanka, and I ran into a writer who I very much like, Shyam Selvadurai, in the best-known bookshop in Colombo. He was picking up books, and he got to one book and said, “And this one I wish I had written.” And I hadn’t heard someone say that before. I was choosing between two books, my suitcase had hit the weight limit, and so I chose that one. The other book, the one I didn’t choose, became very well-known. The one he wished he had written was not quite as successful.

McCracken: I don’t feel jealous of someone like Richard Price. It would be like looking at a basketball player and saying, “That looks great.” Sugi, do you have a book?

Ganeshananthan: Not where envy applies. There are certain books with extensive passages I can quote. There’s a page of The Giant’s House that I’m especially fond of, and the book is bent in that specific place. It’s when Peggy’s on the bus. “Sometimes you have to marry your tower, your tiny room. You must take great interest in everything, a spinning wheel, a perfect singe bed, the sound of someone breathing on the other side of the door.” It’s one of my all-time favorite passages of anything. For me, there are more pages than books.

But Shyam Selvadurai ‘s Funny Boy is the first book I read where I thought, I wish I could have done that.

But Shyam Selvadurai ‘s Funny Boy is the first book I read where I thought, I wish I could have done that.

Elizabeth, what are your most beloved books? The books that you keep on your night-stand, your best-friend books?

McCracken: Grace Paley, The Collected Stories. “Gloomy Tune” is maybe my favorite piece of fiction in the world. My friend Paul Lisicky suggested I bring that in for today’s craft talk. But I could picture it—I would say, “How does this work?” And people would pose theories, and I would say “WRONG! You can’t figure out how it works, that’s why it’s so great! You can’t unravel it!” If anybody said anything negative about it, I would have burst into tears and fled from the room.

Ganeshananthan: I’ve been fortunate to have a lot of teachers who are not just good writers but also exceptional humans. One of the great disappointments of becoming an adult was the realization that a lot of people who made art that I loved were not nice. I was sort of crushed by that, that you didn’t have to be a good person to make good art. I understood that life wasn’t going to be fair, but I really would have preferred that it had been.

McCracken: I used to think you have to be a good human being to be a good teacher, but now I know it’s my “learning style.” I don’t learn much from people who aren’t good people—another reason why Allan Gurganus and Sue Miller were such fantastic teachers for me. But there are a lot of people who learn from conflict and from reaction.

Sugi, you teach a Women and Humor class, and Elizabeth, your books are full of memorable jokes and liners. Stand-up comedians will work for years to come up with just one hour of material. How are all these jokes born?

McCracken: The way you write is dictated so much by the way you process the world—another reason it’s impossible to give lots of rules for writing fiction. Cracking wise is my natural state. It’s why I enjoy Twitter—it’s a repository for all those idle thoughts I used to try to cram into stories only to have someone say, “Yes, that’s very funny, and it’s got nothing to do with what the story, and you need to take it out.”

Sometimes people have said of things I have written “Oh, you’re so funny!” And I want to say, “That was very serious and from the deepest part of my soul!”

I love stand-up, but I can’t imagine being a comedian. In your early days, it has to be one of the worst jobs in the world. It’s bad enough being exposed as a writer, but getting your job evaluation every night, in public?

Last week, I was listening to the podcast You Made It Weird with Pete Holmes, and one comic was saying how embarrassed he was by his first years of material, but that in the beginning, you can’t be yourself. You haven’t earned a voice, and you have to be interchangeable with the next five guys to get regular gigs. It’s very different from writers, who are looking for a singular voice, first thing.

McCracken: I listen to WTF with Marc Maron, and he says the same thing. I think the nice thing about being a writer is that all those first-five-minutes are locked away in a drawer.

Who are some of your favorite comics?

McCracken: My favorite current stand-up is Maria Bamford, favorite all-time, Richard Pryor. I like any comic in which you can see the soul through the jokes. There’s an English double act—for some reason, comedy teams still exist and thrive in England in a way they don’t here—called Mitchell and Webb, whom I love very much. They star in a sitcom called Peep Show, as well as a sketch series.

Maria Bamford seeing her high-school nemesis at Target! I guess I like to feel tense and sad and furious while I laugh.

Ganeshananthan: I’ve been looking for ways to buffer my research material to make it…tolerable, and so watching an enormous amount of stand-up comedy. My undergraduate students introduced me to Louis C.K., and an Aussie friend of mine pointed me to Tim Minchin. Rachel Dry, a college friend who is now a Knight-Wallace Fellow [at the University of Michigan], audited the Women and Humor class I taught last term. She does stand-up, and I go to watch her perform.

The students in my women and humor class, at first, don’t think of fiction as funny. They think of fiction as something ponderous. And then I get to introduce them to Elizabeth, to Lorrie Moore.

They think of Ethan Frome, which I hold singly responsible for ruining a lot of young readership before it’s really begun to read adult fiction.

McCracken: I had to read it three times, growing up in New England.

Do you stockpile jokes, Elizabeth, or are they only born from a character’s voice?

McCracken: Not necessarily jokes, but metaphors, really. As a reader, a perfect metaphor is one of my favorite things to read. There are metaphors in my work that were born when I was out in the world and saw something, and I just instantly understood something else.