Is there anything more sci-fi than the deep past? We can look at it and see ourselves, or we can look at it and find cautionary tales, or affirmations of cherished values, or exotic imaginings that recreate the very foundations upon which we stand. When I first picked up Jamie Yourdon’s new novel, The Space Between Two Deaths, I didn’t know what to expect. What I found was an eerie connection to a different time and place that has made me think differently about the world. What I found, too, was new appreciation for what might be called historical fiction, but is actually very new and real.

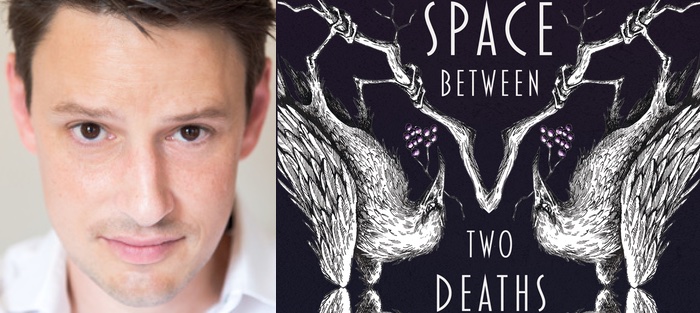

Jamie Yourdon was my student in the MFA program at the University of Arizona—oh, so many years ago now!—and in the time since he has obviously more than flourished, establishing himself as a writer of provocative and imaginative fiction, first with the novel, Froelich’s Ladder (2016), and, just this month, with The Space Between Two Deaths. As any of you who are teachers know, the secret is we learn from our students—that is the beauty and life in the profession. I’m certainly learning from Jamie. It was a pleasure and an education to read this book and also to chat about some of the more intriguing elements. Here is a glimpse into Jamie’s compelling storytelling and way of looking at the world.

Interview:

Aurelie Sheehan: All novels are acts of imagination, but I’m fascinated by the second set of requirements, constraints, or opportunities provided by a project set in ancient times. What was it like to imagine your way into these people?

Jamie Yourdon: I’ll confess something to you: one of the earliest reviews for The Space Between Two Deaths came from an Assyriologist, who identified an historical inaccuracy in the first sentence of the first page. So . . . I suck at it, I guess?

In all seriousness, I did a fair amount of research and I wrote a work of fiction; I did both. I wanted to know whether ancient Sumeria had been a monotheistic or polytheistic culture, and what legal rights had been afforded to women, but I also wanted the freedom to invent grieving rites. I imagined characters burying mirrors or holding rocks under their tongues—and while no one actually did those things (or maybe they did?), they spoke to the necessity of mourning. I’ve sat shiva. I’ve scattered ashes. I find it hard to believe that people are so different across time and space. There’s plenty of research to suggest we’re all shaped by societal pressures acting against us. The nature of those pressures depends upon the society, but basic emotions—our human imperatives—remain the same. Love of family. Fear of failure. Rejection of responsibility. Desire for inclusion. I felt that if my characters’ decisions were motivated by recognizable concerns then they’d be recognizable to the reader, regardless of what era the various parties arrived from.

Having said all of that, I relied on my imagination to breathe life into these characters; they weren’t based on primary sources. Maybe I should include a warning for any future Assyriologists that I play fast and loose with the facts? Also, Nippur didn’t have an army—I stand corrected.

My next question, then, relates to just that: research. What was your process of researching the Sumerian culture, and how did that impact your writing process?

My next question, then, relates to just that: research. What was your process of researching the Sumerian culture, and how did that impact your writing process?

The most fascinating thing for me was when I discovered an appendix of Akkadian words—the language being spoken at the time. It’s one thing to read a poem like Gilgamesh in translation, but another thing entirely to shape those syllables with my own tongue. I harvested a bunch of proper nouns for my characters’ names. Temen means “foundation.” Meshara means “all the oaths.” Ziz means “moth.” Garash means “catastrophe,” Hazi means “Axe,” and Wasu means “small.”

I wanted to set my plot in a time and place where the netherworld felt more tangible to the protagonists, less remote. Of course, I’m projecting my sense of ancient Sumerians upon ancient Sumer and its people, but it felt more plausible than, say, 1850s Oregon (where and when I set my previous novel, Froelich’s Ladder). To have these words for the characters’ names loaned them authenticity.

Another Akkadian word I use in the book is mitu; it means “dead person.” Originally, that was the working title, Mitu—but then, in 2018, the #MeToo movement gained worldwide recognition and became lodged in our consciousness. I emailed my agent to say, “Look, either this is so perfectly on the nose that we can only marvel at the serendipity . . . or I’ll just change the title.” We opted for the latter. What I was going for, with Mitu, was an acknowledgement that the act of grieving can make a person feel dead. While the themes of abuse and powerlessness are certainly prevelant throughout the plot, using “mitu” to evoke “me too,” or knowing that it could, felt like borrowed finery.

That is really something—I love hearing about these serendipitous moments that offer us a new reading of our own work. That being said, gender roles and class stratification, specifically as they impact power and freedom, really do feel quite at the heart of this novel. Was this theme something you discovered as you wrote, or was it an original motivation for writing?

For me, there always comes a time—usually toward the end of a first draft—when a novel reveals what it’s truly about. With The Space Between Two Deaths, I was writing a scene between Ziz (a young girl) and Wasu (a young boy) in which Wasu had the power. When his mother entered the room, she assumed the power—and I thought, “Oh! It’s a book about power dynamics!” After that I was able to revisit every scene I’d already written and ask myself (1) who has the power, (2) how does he or she maintain that power, and (3) how do/es the person or people without power stay safe?

To my mind, the characters with power lived in constant fear, because they knew that losing their power might result in punishment and retribution. Their fear made them cruel—which, ironically, increased the chances of punishment and retribution. Meanwhile, I watched as the characters without power made themselves small. They were so amazingly, achingly supple, it broke my heart. In scene after scene, they maneuvered to make themselves less visible, or to be more favorably perceived, if they had to be perceived at all. Everyone suffered from that power dynamic. No one was free.

I really appreciate your description of how this is working in the book. It’s illuminating, and also speaks to the necessity for compassion in writing. To be aware of power dynamics, as you are, is to care about the characters who are struggling to make themselves likeable, or to disappear into the woodwork, or otherwise to survive. It’s fascinating to think about how this works in the present day and also in ancient times—like nothing has ever changed.

I’ve always been a fan of your work, Aurelie. I imagine power dynamics are something you experience in the world and subsequently explore in your fiction?

Yes, I have written about power dynamics, for sure, sometimes consciously, but sometimes less so. They’re always at least in the background. In the pop culture category, I was very aware of the power dynamic vibe when watching Game of Thrones, which depicts such raw fights for power in quite an engaging way. My fiction doesn’t usually involve crowns and kingdoms, but as you say, the dynamics are always there. Thinking of power as a force in fiction is helpful to me as a writer, because it can provide a way to measure energy and create focus and dynamism in a given piece. It’s an invisible force that has visible consequences.

Speaking of energy, the female characters in this book are forces to be reckoned with. Ziz, in particular, is channeling a kind of energy that is, perhaps, needed even today. I appreciate how you’re able to create these strong characters who also have challenges of their own. Can you talk a little bit about how the plot developed around Ziz?

Originally, my sympathies lay with Temen, Ziz’s father and Meshara’s husband. But I came to realize that Temen wasn’t my protagonist; he was an antagonist. His decisions, selfishly made, put Ziz and Meshara at risk. At the time I was writing The Space Between Two Deaths I was going through a divorce—and while Portland, Oregon is a far cry from ancient Sumeria, I was concerned that my own actions were harming the people I loved. I found it difficult to be the hero of my own story.

Ziz has the onus of being a child. She has very little agency. So I funneled all my care into her: what she was thinking, how she inhabited her body, what frightened her, what made her feel safe. I wanted to give her story a resolution that was both empowering and realistic, to the extent that realism had a place in the narrative.

I think of something you said to me, eons ago, at the Univeristy of Arizona—how I wrote about responsibility. (You may not recall. It was a short story about a little boy who gets lost at the zoo and is ultimately remanded to Protective Services.) It occurs to me now that it’s impossible to recognize a trait in someone else without harboring it yourself. How and where do you channel the same energy in your work?

Hey, I remember that story! Okay. Well . . . probably in every character I’ve ever written there is a little bit of myself, certainly of my experience of the world. The interesting thing to think about is those characters whom we might find hateful in certain ways, and what element of our own selves we’re dealing with there. I guess I’ve probably written characters I find appalling and would never want to be like, but then I also find myself writing characters I’d like to be just a little bit more like, at times (a.k.a., smokers). And finally, I might write characters whom I truly admire—or whom I love in an unexpected way.

When you talk about Ziz, I hear the tenderness you feel for her. In that, you found her strength. She is constrained by being a kid, but she also takes actions when she can—and I admire her for them, and you for finding that in her. I especially admire how, in this book, you are reimagining people from a vastly different time and place, and yet they are still so close to us, and so familiar.

But enough about people—let’s talk about the crow, one of my very favorite characters in the novel. Can you describe the challenges and pleasures of writing into the character of a bird?

I wish I remember deciding to write a talking crow! In a sense, the crow preceded the novel. The Space Between Two Deaths originated as a man traveling to the netherworld to retrieve his dead father, but the voice of the crow was always in my head. He shouted in all-caps; he harangued and mocked and agonized. If Ziz and Meshara experience gender and class dynamics, the crow is representative of an abusive relationship—the dynamic shared by a victim and an assailant. The crow has something taken from him that he desperately wants back, in order to make himself whole. He pleads, negotiates, and demands. He compromises and sacrifices. I don’t remember the experience of writing him as being entirely pleasant. Necessary, yes, but not pleasant. I hear him still.

Have you ever given voice to a character who’s haunted you?

In a way, that’s the only kind of character I can write, at least in a satisfying way. You probably feel this too, as a novelist. You end up being haunted by the whole cast of characters, and as long as you’re writing the novel, they’re absolutely alive. And when you finish writing the novel, it’s a little sad, because the act of creation keeps that window open between worlds (speaking of journeys between). When the book is complete, they don’t disappear, but the connection is slightly distanced. You can’t live with them on a daily basis anymore. But at least there is the pleasure of sharing them with others.

On that subject, I did want to get at the spiritual dimension of this novel. The fluidity between the worlds of the living and the dead is obviously very significant. Can you let me in on any unique challenges or pleasures taking on these otherworldy components had for you?

One more confession before we’re through. I’d already written a scene that was set in the netherworld when I began reading Lincoln In The Bardo by George Saunders. Now, I love George Saunders. I had a dog named “Saunders.” My best man invited George Saunders to my bachelor party. (He declined, in a very sweet email, but suggested that my friend splurge on a limo while claiming that he, George Saunders, had paid for it.) And I thought Lincoln In The Bardo was a gorgeous, heartrending not-quite-a-novel. However, toward the end, Saunders describes a scene from the afterlife . . . and it’s just awful, his rendering of the afterlife. I don’t mean objectively awful; I mean, as conceived by arguably the most creative American writer alive today, it’s terrible. It’s hokey! Then I looked at my own scene and thought, “Holy shit! This is even worse!”

So I threw away what I’d already written and attempted a much broader, more imaginative approach to describing the netherworld. The laws of physics need not apply. Well, what did that mean? Whom would the netherworld be populated by, and would they recognize each other? I tried to identify what fears might be universal, primal, and stomach-lurching—falling, asphyxiating—and how I could capture them in various tableaus. I think my initial scene involved a dark hallway with, like, a torch. This was far more descriptive and far denser, content straight from my id. Not like anything I’d ever put on the page before, which, given the subject matter, seemed appropriate.

My confession, by the way, is that I think poorly about George Saunders’s afterlife. But it was a teaching moment—he showed me what I needed to do. Hopefully he can indulge my pique.

I can only hope the afterlife is hokey.