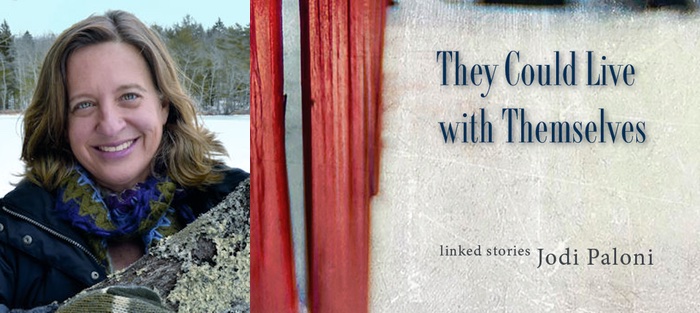

Back in the spring of 2011 I served as Jodi Paloni’s advisor for her fourth semester at the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in Writing program. This was the big crunch semester, the one where Vermont students have to present their Creative Thesis in order to graduate, and also work up a half-hour craft lecture on a subject of their choice. Jodi’s lecture topic was “Tears of the Gods: How Protagonists in Linked Story Collections are Polished Into Lustrous Pearls,” which made sense, because she was crazy addicted to interrelated story collections. She was writing one herself, a Creative Thesis that has now morphed beautifully into her first book, They Could Live with Themselves, just published by Press 53.

For the final packet of work she sent to me that semester, Jodi did something highly unusual, something none of my many advisees at VCFA had ever done. Instead of sending in final revisions of stories for a definitive thesis polish, she instead sent me two entirely new stories. They were, she said, “pretty rough.” Actually, they were stunners, breakthrough stories where she put together all the strands of what makes her fiction so distinctive: a wry empathy, characters with hidden emotion complexity that slowly reveals itself, a conflicted sense of community, and a spot-on descriptive eye. They were easily added to her thesis, the best example of stealing literary home base I’ve ever witnessed.

Since then I’ve kept up with Jodi Paloni’s career with interest and pride as she won second place in the 2012 Raymond Carver Short Story Contest, and then won the 2013 Short Story America Prize. Her stories have appeared in upstreet, Whitefish Review (selected by guest editor Pam Houston), Carve Magazine, Contrary Magazine, and elsewhere. She lives and writes in Maine, serves on the fiction committee for the Brattleboro Literary Festival, and is an active member of the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance.

Interview:

Philip Graham: Let’s start by talking about the title of your collection, They Could Live with Themselves. I think the use of the conditional works so well here. The characters in these stories could live with themselves—their contradictions and ambitions—if only they could manage to find a way.

Jodi Paloni: It’s interesting about titles. Some come easily. For others, you have to rely on friends and early readers for ideas. I don’t know if you remember this, but you had a hand in the origin of this one. I needed a title as part of my creative thesis submission and you suggested that I read through the manuscript to see if a line or a phrase jumped out from one of the stories, one that summed up the whole of the parts. I sent you a list of my ideas and you wrote back in favor of two. They Could Live With Themselves was one of them. It happened to be my first choice.

It originally came from a line in the opening paragraph of the first story I ever wrote about Stark Run. It was the morning after a tragedy took place at the community fair:

Perhaps spouses took more time with each other when they said good-bye, as if a kind gesture could stave off trouble. If something tragic were to happen, an accident, they could live with themselves, having said I love you.

The funny thing is, that story never made it into the collection, but the title stuck and it seems to work.

Yes, I noticed that as I was reading. I kept wondering, When is that phrase going to come up? But then, as it seemed increasingly likely that it wouldn’t, I thought, Well, how does the title apply to the collection’s meaning or intent? And then I began to see rich connections.

It can be interpreted in a number of ways. My editor likes it because it creates mystery, inviting the reader inside the book. What did these people do that they have to live with?

I like the play on words. For example, in almost every story, the protagonist is a loner, either by choice or by circumstance, until the “important other” comes along. In essence, these characters do live with themselves, in their own little worlds–holed up in an art shed, curled in a black bear costume, swimming in an empty pool–and could (there’s the conditional) continue to self-isolate. But they also could make the choice to step into some new reality that includes an alliance.

I think about how in real life we all sort of fumble along, attempt to make sense of the tough stuff. We make mistakes, but we try to do the best we can. The title suggests a positive stance. Yes, we can learn to live with ourselves–our quirks and faults, the messes we’re dealt. We have to. Read in that way, there’s a redemptive quality. I’m a fan of at least the possibility for redemption in fiction.

But not in an easy way, I think, which is why your stories are so successful. For example, in an early story, “The Third Element,” Meredith, the high school art teacher, hires a recent former student, Sky, to paint her rather run-down house. They intrigue each other in ways they can’t quite articulate, and it isn’t until the final story in the collection, “The Physics of Light,” that they realize just what sort of kindred spirits they might be.

But not in an easy way, I think, which is why your stories are so successful. For example, in an early story, “The Third Element,” Meredith, the high school art teacher, hires a recent former student, Sky, to paint her rather run-down house. They intrigue each other in ways they can’t quite articulate, and it isn’t until the final story in the collection, “The Physics of Light,” that they realize just what sort of kindred spirits they might be.

Ah, yes, Meredith and Sky, kindred for sure, both with strong ties to home and deep longings to bust out in some way.

“The Third Element” tells Meredith’s very private story, yet Sky inadvertently plays a significant role in her shift. How that happens, intrigues me. He intrigues me. I wasn’t surprised when he began popping in and out of other narratives. All along, I knew he had his own story, and that it would involve Meredith. I also knew I couldn’t rush it.

Yeah, Sky. I think he intrigues the reader, too. In the very first story, “Molly Sings the Blues,” we see him through his mother’s eyes (including her memory of his conception!), and he seems at first a diffident sort, but kind, in a mysterious way. Other characters are drawn to him. I kept noting his return, in minor roles, in subsequent stories, and wondered about that, where it might lead.

I wondered, too. “The Physics of Light” came late in the game, as in, after the collection was accepted. My editor and I talked about the ways the overall linkages were working and places where the thread dropped a stitch. Every time I asked myself what is the missing link, I’d think about Sky, how he came into the world, how he loved the farm and the town and wanted to help people. He seemed sweet and good, almost too good, so I knew there had to be something darker brewing beneath the surface.

As it turns out, he questions everything he’s most certain about. I think it’s the river in him, always right there, but always moving. In the end, it’s his narrative that arcs throughout the book, and, in essence, he represents the liminal place that resides in all of the characters. Some people say this book is about loss and regret, others say desire, and it’s about all of that, but it also toys with the malleability of boundaries and the influence of thresholds. I think it’s mostly about forward motion.

How interesting, that it took you a while to understand his importance in the over-all collection, and if he were navigating some hidden current inside you.

Well, as I look back, what better character out of the whole bunch–a young person from a large and respected family, greatly cherished, and fully rooted–to question the status quo? He’s sensitive and he’s got a camera in his hands. By giving him a lens, literally, I gave him the power to zoom in and zoom out on the town.

All of this was quite unintentional, Philip. It’s as if in all of the years spent writing these stories, something larger, overall, was happening that I didn’t know about. It reminds me of the Peter Turchi book you assigned me at Vermont College. Remember that?

Remember? It’s one of my favorite books! I’ve taught it a lot, and I often recommend it to my graduate students—as I did with you. What did you especially find valuable in it?

The idea that the way a map works (a paper map, at least) is dependent on the geography of what’s not seen. If everything between, let’s say, my house to your house–every store, every tree, every road sign–was depicted, our view would be so cluttered, we couldn’t possibly find a path. Essentially, what’s omitted is what provides the backdrop. In my collection, Sky is a “white space” or a “negative space” character, in a sense, until he’s not. And when his story moves to the forefront on the page, it somehow pulls all of the other stories with it. I don’t want to give anything away, but Sky’s ultimate choice does have the potential to ask everyone touched by it to question the status quo.

The idea that the way a map works (a paper map, at least) is dependent on the geography of what’s not seen. If everything between, let’s say, my house to your house–every store, every tree, every road sign–was depicted, our view would be so cluttered, we couldn’t possibly find a path. Essentially, what’s omitted is what provides the backdrop. In my collection, Sky is a “white space” or a “negative space” character, in a sense, until he’s not. And when his story moves to the forefront on the page, it somehow pulls all of the other stories with it. I don’t want to give anything away, but Sky’s ultimate choice does have the potential to ask everyone touched by it to question the status quo.

Turchi also explores ideas about how we can arrive at our fictions by shuffling through them in the dark, seeking direction as we go. We begin with what’s directly in front of us, and maybe we have a vague overarching plan, a bird’s eye view, but we write to pay attention to what unfolds. Most of what unfolded for Sky wasn’t seen until it arrived on the page. I hope I’m making sense. It was rather mysterious. Sky’s evolution was built little by little in each story as an unconscious aside. It was as if he was priming (off-page) to make a bigger impression in the final pages.

I love it when the uncanny becomes part of the fiction writing process, that moment of weird clarity when a writer finally realizes just what sort of duet he or she has been dancing with the unconscious.

I’d say that happens quite a bit to me, especially at the drafting stage. I never sit down with a clear idea for a story. Instead, I’m out walking the dirt road or throwing the ball to the dog and, like Ms. Bellamy, I start to narrate in my head. I rush for the nearest piece of paper, or now, I use Notes on my phone and jot down enough of the “voice” to recall it at the desk. It’s been that way for every story.

You should take more walks!

True. Actually, “Accommodations” came in a little differently. A friend was reading some of my stories and gave me the feedback that they sometimes rambled a bit and tried to do too much in too few pages. She said, Why not try this. Put two or three characters in a small space where they can’t get out. Another reader said, Don’t leave your characters alone for too long. It was the only story where I actually sat down as part of a specific exercise and I merged the advice. I had my usual “loner,” brought in the stranger, and stranded them in a general store in an ice storm. Where the unconscious stepped in was that there was a third character waiting in the wings, and I didn’t know it until Wren knew it. I’m actually getting a chill as I speak. These are the moments I love the most about writing.

“Accommodations” is one of my favorite stories in the collection, and I’d love to talk about that later. But for the moment, I can’t help observing that you’ve mentioned the term “status quo” a couple of times. Perhaps you’d like to talk a bit about how that works in your fictional town of Stark Run?

Aren’t all stories about characters on the brink of some great, or not so great, change? They long for something different, to put an end to sadness, to finalize a decision, to open to love. I’ve been trying to write a novel, but I keep going back to stories. I think it’s because with the short form, I get to play more often with all the many variations on the theme of transformation.

Generally, my characters are dealing with loss of some kind. These are fundamentally sad people who plod along in their interior worlds against the backdrop of their small town (the status quo). There are no hurricanes or bloody fist fights. No one dumps a table over at a Thanksgiving dinner party. With these folks, the trouble stews in the heart.

Ah, “trouble stews in the heart,” I love that. There’s certainly a lot of that in the story “Accommodations.” Wren is working in a late night convenience store and is just trying to lock up for the evening, when a man knocks on the glass doors. He needs gas. At first, this seems like a small problem. Wren knows she has difficulties saying “no” to others, and “yes” to herself. So, this should be easy enough: No, we’re closed. But it’s not that simple, and the story negotiates nicely the changing meanings of yes and no as it relates to Wren’s inner life.

Yes, it seems quite simple at the start, and then come those plots twists and turns, but also the complex give and take between two characters trapped together with a now shared situation on their hands, the clock ticking, where the antagonist’s story, by the very nature of his story, urges the protagonist’s forward movement. Is it probable that the mere interaction of one person’s silent struggle given voice can catapult another person into a revelation that promotes change? Yes! It happens every day.

There are some twists and turns, some surprises in this story, but they never feel forced, perhaps because Wren is always evaluating what to do next, how to respond to this unhappy man and his dilemma.

It brings me back to the potency of… enter the stranger. Expectancy automatically gets thrown upon the unexpected alliance. In my stories this happens often: an empty-nester’s solitude is intruded upon by a grungy pregnant woman, a retiree becomes obsessed with a trio of teenaged girl who repeatedly cut school, a young girl’s breaking point is witnessed by a bear-like tattooed orderly in an elevator.

Which brings us back to the title, They Could Live With Themselves, but maybe they’re better off living in the presence of one another.

Ah yes, they could live with themselves, but how much better, perhaps, to make the leap into the lives of others. That’s an essential tension in your collection’s title, and in all our lives, actually…

So true. Lately, the main reason I write fiction is to grapple with the perennial question: Where does the “I” stop and the “you” begin? I’ve been reading Rilke. I think the following lines relate well to our conversation about Turchi’s work, linked stories, and the archetypal “other”…

Though we do not know our exact location,

We are held in place by what links us.

Across trackless distances

Antennas sense each other.

(from “Sonnets to Orpheus I, 12” by Rainer Maria Rilke)

My hope is that the notion of “trackless distances” opens up space within and between and across these stories for the reader to discover where he or she might presently stand. That’s what I do as a reader. You know, talk to myself as I read along. Say things like: I’ve done that! Would I do it again? Or, That sounds like my mother? Do I sound like my mother? Or, he reminds me of that guy I dated in college. Wonder what he’s up to now? But mostly, reading makes me dreamy, as in, I wish I had the guts to just grab a backpack, jump on a train, and go. And maybe, in a way, every time I write a new story, I get to jump on that train.