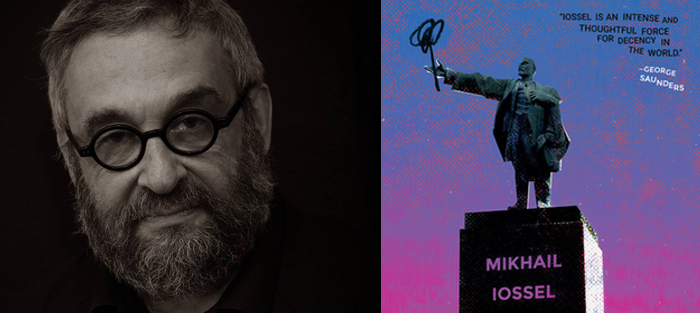

Mikhail Iossel was thirty years old in 1986 when he emigrated from the Soviet Union to the United States. That first year, Iossel lived in the outskirts of Boston, Brookline, with seven roommates. The only TV channel he had was the Boston Celtics channel, which means most of the English he was hearing was made up of the manic rants of Johnny Most.

A samizdat writer from Club 81 and a translator of American fiction and poetry, Iossel had already launched his writing career before leaving the Soviet Union. In the United States, he studied with Thomas Williams at the University of New Hampshire, then became a Stegner Fellow at Stanford, working with his mentor, Gilbert Sorrentino (whose work he translated into Russian in the Soviet Union). Subsequently, he was the recipient of a Guggenheim fellowship and a National Endowment for the Arts award. Iossel is the author of the collection Every Hunter Wants to Know (W.W. Norton, 1991) and co-editor with Jeff Parker of two anthologies: Amerika (Dalkey Archive, 2004) and Rasskazy: New Fiction From a New Russian (Tin House Books, 2009). He is also the founding director of the Summer Literary Seminars, which organizes international literary programs in Russia, Kenya, Lithuania, Italy, and elsewhere. He teaches at Concordia University in Montreal.

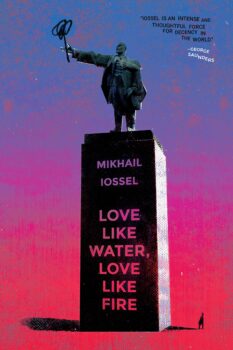

In his latest collection, Love Like Fire, Love Like Water (Bellevue Literary Press), Iossel writes about the Soviet Union in what he calls “a foreigner’s English.” As the writer of a novel about navigating identity through language, specifically Russian, I was eager to talk to Iossel not only about his work, but also this element of his writing practice. We discussed how to put memory into language and whether that memory in writing is true or some kind of self-censored sentimentality.

Interview:

Ian Ross Singleton: How, or why, did you begin writing in English?

Mikhail Iossel: I was looking for a different way to deal with my life by starting to write in English. No one had put this responsibility on me, and it doesn’t really exist. But I feel that there is a meaning to my writing in English. I felt accountable to my own memories and to this story of my life and to the story of the life around me in a place that no longer exists and the life that no longer is there in a renamed city. That was my project at first: to remove myself from my past by means of trying to start writing in English. Russian engaged me and my nostalgia. I thought I had made a fatal mistake in my life. Of course I couldn’t do anything but be completely adequate to the sentence at hand. I had to write a very simple sentence, and it had to make sense. One and the next…one step to the left or to the right. It’s like walking through a minefield. So I was negotiating that narrow path of telling a story by means of those brief, functional sentences. And then I had a paragraph. And then I had another one. And that’s how the story grew. It didn’t happen overnight.

So are you translating from Russian to English in your mind? Or only thinking in English?

If I were to define my writing, I would say that it’s writing in Russian but in English. It’s Russian sentences in English. But I can only speak English in a correct way. I can’t necessarily speak English incorrectly in the correct way. What I’m trying to do is come to a point where language no longer matters. I can write short, simple declarative sentences. But I prefer not to. I’m trying to hit my stride. I have to make myself happy with the English first. The English provides a bit of a resistance. I read quickly in Russian, perhaps too quickly. But I was reading a pre-1917 edition of War and Peace. And I was on a bus from Montreal to New York City. The pre-Soviet edition still had the letters excised from the Russian alphabet by the Bolsheviks. I was tired, and I was reading slowly. And it made for a close reading. I began to notice things about the text which I had never noticed before. The difference of the language made it somewhat estranged. Through estrangement I’m telling about a life that is largely unfamiliar to readers of English. Writing about my memories in English also lets me estrange myself from myself. Memory is everything, because I have a whole life behind my back.

What I write is nonetheless autofiction, because memory is mostly unreliable. Memory is really imagination pointing backwards. On Facebook, I would do this kind of Oulipian exercise where I would write a memory, and all I would have to do would be to correct syntax and so forth. By the same token, sometimes I would try to approach a memory or reconfigure it into a story, and it would immediately rebuff me. And I would immediately realize that this frontal assault won’t work. With the story “The Night We Were Told Brezhnev Was Dead,” I meant to write something quickly. But it didn’t work that way. There was too much material there. I was coming home from work on the night shift as a security guard for a roller coaster at the Leningrad Central Park of Culture and Leisure, called “American Hills.” And a friend called me up, neglected to use our code for safe calls, and told me to turn on the TV. And I turn on the TV, and it’s Swan Lake. Immediately my heart jumps. We went into this overblown satirical routine. How, if it’s true, are we going to live now? It’s completely impossible. How we couldn’t imagine our lives without him. There was this momentous feeling that our world had changed drastically and dramatically. We’d been waiting for this moment for years. That’s how it all started ending. But, of course, even in my groggy state, I had to compose myself because I have to say something for the benefit of whoever’s listening to the conversation.

What I write is nonetheless autofiction, because memory is mostly unreliable. Memory is really imagination pointing backwards. On Facebook, I would do this kind of Oulipian exercise where I would write a memory, and all I would have to do would be to correct syntax and so forth. By the same token, sometimes I would try to approach a memory or reconfigure it into a story, and it would immediately rebuff me. And I would immediately realize that this frontal assault won’t work. With the story “The Night We Were Told Brezhnev Was Dead,” I meant to write something quickly. But it didn’t work that way. There was too much material there. I was coming home from work on the night shift as a security guard for a roller coaster at the Leningrad Central Park of Culture and Leisure, called “American Hills.” And a friend called me up, neglected to use our code for safe calls, and told me to turn on the TV. And I turn on the TV, and it’s Swan Lake. Immediately my heart jumps. We went into this overblown satirical routine. How, if it’s true, are we going to live now? It’s completely impossible. How we couldn’t imagine our lives without him. There was this momentous feeling that our world had changed drastically and dramatically. We’d been waiting for this moment for years. That’s how it all started ending. But, of course, even in my groggy state, I had to compose myself because I have to say something for the benefit of whoever’s listening to the conversation.

You and your friend in that story keep repeating the word “heartbroken.” It’s clear that you’re using it ironically. What was the word in Russian?

We were using some kind of tried literary language such as наши сердца разбиты (nashi serdtsa razbity), something like that. It was the official language of mourners.

In “Moscow Windows,” there’s a quote from Dostoyevsky: “You are told a lot about your education, but some beautiful, sacred memory, preserved since childhood, is perhaps the best education of all. If a man carries many such memories into life with him, he is saved for the rest of his days. And even if only one good memory is left in our hearts, it may also be the instrument of our salvation one day.” Is that what memory is for you?

You can’t change the past. You can reinvent it. Memory’s your accomplice in that. Memory is like water. Memory is imagination pointing backwards. With autofiction, essentially, I can rearrange my memories. I can bring in other people’s memories. I can reinvent something completely. I didn’t enter into a contract with the reader that it’s going to be the whole truth. Because there is no such thing as the whole truth. If you’re writing a piece of nonfiction, you sort of enter into this unspoken, or sometimes spoken, contract with the reader that you’re not going to play games with them. I’ll tell you how it was. But I kind of believe in other things. If it’s well written, it’s true. If it’s poorly written, it’s not. Even if it’s how it happened. So, in my case, whatever is more vivid, that’s the true memory. Sometimes it may or may not be correct. I try to be correct because, if not, I would be deceiving myself. I do think that memory is what sustains people. Me definitely. Memory is the starting point of excitement, usually. That’s how any story starts, I don’t write stories with a premise that I don’t relate to on that level.

It’s a creative act: “The imagination pointing backwards.”

And it’s not with any attempt to delude or deceive. It’s simply that, if the memory is strong, then that’s true.

In the story “Our Entire Nation,” the character writes different names and words all of which can be spelled with the letters A M E R I K A. Your memories are haunted by America. It seems that the normal Soviet childhood was haunted by America in a way that an American childhood wasn’t haunted by the Soviet Union or, now, Russia. Is there something particularly Soviet about your ideas about memory? Is there some place that’s beautiful and far away?

Well, generally, up to a certain point in childhood, America is just a symbol of everything that is bad and evil. They’re not like us. It’s just something infinitely scary. And we are all very fortunate not to have been born there because it could easily have happened. And that would be a disaster. As a little child, I had a drawing. It was something almost unbelievably hideous, some human-like creature. And that’s what I called America. It was scary. It was the ultimate not us, the un-us.

Well, generally, up to a certain point in childhood, America is just a symbol of everything that is bad and evil. They’re not like us. It’s just something infinitely scary. And we are all very fortunate not to have been born there because it could easily have happened. And that would be a disaster. As a little child, I had a drawing. It was something almost unbelievably hideous, some human-like creature. And that’s what I called America. It was scary. It was the ultimate not us, the un-us.

I was thinking of the Yuri Entin song “Прекрасное далёко” (Prekrasnoye Dalyoko) and whether there’s a flipside to this idea that America was the ultimate evil?

Then at some point it turns into a symbol of something very far away, an alternative to our life. There’s a Chekhov story, “Boys” (Мальчики). So that’s the 19th century, of course. And the boys are basically trying to find a way to escape to America. And it’s always been like this, the ultimate alternative to life.

Can you talk about the title novella of the collection?

Like I said before, I just wanted to write what I thought would be a reasonably straightforward reimagination of one night in the life of my grandparents on my mother’s side. That’s what I pieced together from conversations with my grandmother. My grandfather was a fairly prominent комсомол (komsomol) leader in Leningrad, and a number of his colleagues had been arrested and disappeared. At one point, it seems, she managed to get him out of Leningrad. It all started with that photograph preceding the story. It’s a photograph I found among my mother’s photographs. That’s my grandmother and grandfather in Gomel, Belarus, where she apparently took him in order to wait it out. So the story is several minutes in one night in 1939 in Leningrad that lead to this escape in the photograph.

Your grandmother might have saved him?

When news came on the radio that Stalin had died, my grandfather was completely heartbroken. He was covered in tears, and he came into the living room and said to my grandmother, “What are we going to do now? We cannot live without him. We cannot survive.” And she just busted out with curses because, for thirty years, she had kept her mouth shut. And he said, “I lived with an enemy of the people my whole life.” So when I spoke to my friend and said “heartbroken,” I was parroting the language of Soviet-style mourning.

It speaks to the idea of memory. But it’s almost like a memory one wasn’t allowed to have or to keep. The “heartbroken” line was the official memory one was supposed to have. In truth, it was your grandmother’s cursing of Stalin that is the most vivid and thus true memory. And that’s what we hear in her running monologue in “Love Like Fire, Love Like Water.”

It’s hard for us now to imagine. How did people live back then? I asked my grandmother at one point, and she said something non-committal. Basically, it was ordinary life. By day, it was like ordinary life. By night, the city became the sovereign domain of the воронки (voronki), the black ravens. It’s a theme in Soviet literature. There’s Yevgeny Shvartz’ Dragon. The dragon, like in Greek tragedy, needs to have a sacrifice every night. Give him one beautiful young woman, and then this creature stalks off until it’s time for another. It was like a machine that constantly needed to be fed. There was nothing personal. They just basically had разнарядка (raznaryadka). They needed people to disappear. He was an up-and-coming номенклатура (nomenklatura), and he was obviously within the crosshairs. People around him were being arrested, and he believed post factum that they were British or Japanese spies. Lots of people like him had been brainwashed to that extent. And then there is this young woman who is caught up in that horror, the horror of what’s going on. But she has no alternative at that point. So, that particular night, he is spared. They are spared. After that, I imagine, was when the circumstances occurred in which that photograph was taken. She dragged him out of Leningrad to Gomel, Belarus, where she was born. It had the inscription on the back of my mother’s hand. It’s 1939, late summer, and I have no idea what happened to that side of the family. I have no idea what happened to them. My grandparents would never talk about that, and my mother would never talk about that. I don’t know. Did they perish? I don’t know. But I imagined the circumstances. It’s 1939. They need to arrest hundreds. They come into that particular building, into that particular doorway, that подъезд (podyezd), and they start ascending the stairs. That’s the whole story. They are ascending the stairs, that troika…

When you say that you don’t know what happened to part of your family, it almost sounds like you have to make a memory.

I have no idea what happened to my great grandparents on my mother’s side. You know what happens in life. The process of life means that there are fewer and fewer people to whom you can pose questions. And then there comes a point when there is no one to ask. At this point, there is no one for me to ask.

Your grandmother would never have recorded any of this. It was forbidden. Yet you write this long descent into fear, into trauma, from her side. “Love Like Fire, Love Like Water” reminds me of several works of art. One is the recent animated film Nose, by Andrei Khrzhanovsky, about Nikolai Gogol’s story, as well as the Dmitry Shostakovich opera based on it. At first, the film tries to show the absurdity of the Stalinist era. There’s some humor to the absurdity of it, the absurdity of atrocity. But it’s not enough absurdity to capture the atrocity, which, in the end, overwhelms the viewer. Another film that I thought of was Хрусталёв, машину (Khrustalyov, mashinu), Khrustalyov, Get the Car! Those black ravens you mentioned…It’s a very dark story, of course. But what is most significant, I think, is how you’re discussing atrocity in this very personal way. It makes me think of W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. As you write in the novella, your grandmother is looking to the side in that photograph. She’s not at peace. Your grandfather is very calm. He’s having a nice day with his family. But she’s somewhat disturbed. Everything you write about their characters is in that photograph, in those glances. The sentences are long as if they’re attempting to make sense of this. They’re absurdly long. It’s similar to the one-sentence story “Sentence.”

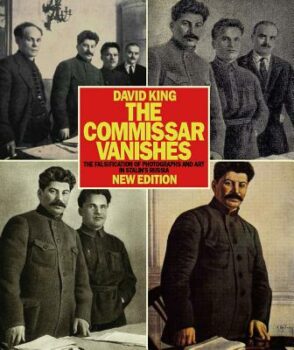

Well, you know, there’s this book about Soviet photographs. It’s called The Commissar Vanishes. It’s about people with Stalin who were “disappeared” because they were executed. It’s what Orwell was writing about in 1984, how people were disappearing in photographs because they were being disappeared. What are you gonna do? Not knowing is a very important element of writing for me. If you know in advance where you’re going to end up, it’s not going to work out well. There is a very interesting and important essay by Donald Barthelme which is called “Not-Knowing.” It’s precisely about that ratio of knowing and not knowing in your writing. Even in the context of writing about something that you think you remember. When you envision it, you still have the ability to surprise yourself to some extent. You have the ability to discover something in the process of writing.

Well, you know, there’s this book about Soviet photographs. It’s called The Commissar Vanishes. It’s about people with Stalin who were “disappeared” because they were executed. It’s what Orwell was writing about in 1984, how people were disappearing in photographs because they were being disappeared. What are you gonna do? Not knowing is a very important element of writing for me. If you know in advance where you’re going to end up, it’s not going to work out well. There is a very interesting and important essay by Donald Barthelme which is called “Not-Knowing.” It’s precisely about that ratio of knowing and not knowing in your writing. Even in the context of writing about something that you think you remember. When you envision it, you still have the ability to surprise yourself to some extent. You have the ability to discover something in the process of writing.

Is it maybe similar to John Keats’ “negative capability”?

Yes.

So is Sebald an influence?

Well, the photograph gave me an idea. Why are they in Belarus in the summer of 1939? He is this tireless party worker. All of his close friends were at one point or another arrested, and he nonetheless believed the party. How did they live in that world? What was it like? She sees them. They start ascending the staircase. So it’s about the process of trying to imagine it too.

You received inspiration from this photograph. You tried to depict that situation in which they lived. Your writing comes out of this setting. So, in your writing, can a reader detect some kind of essence of Leningrad?

I was born and lived in that city my entire Soviet life, with only the brief period at age five when I was in Moscow with my grandparents. I spent the first eight years of my life in a communal apartment in the roiling Dostoyevskyan heart of midtown Leningrad. But then we moved to the outskirts of the city, to the new micro-districts, to Cosmonauts Avenue. It was a cooperative apartment. The rest of my life was spent in that general part of the city. The apartment I had the last seven years of my life in the Soviet Union was a ten-minute walk from the Park of Victory metro station. The essence of Leningrad, however, is the essence of St. Petersburg. It’s unlike Moscow. It’s a city of basements, underground places. That’s partly why the samizdat scene was so much richer, and more literary, in Leningrad. Moscow was all on the surface, and it was saturated with foreigners. Leningrad is the city of basements. Also it’s the city of great tension between the facades and what’s behind them. There are the Italian palazzos. And then there are the veritable cities of the courtyards. It’s a whole river of stone, like Cheever’s “The Swimmer.” There is real hardship there. That’s Dostoyevsky. Those courtyards. Petersburg was essentially built by Peter the Great to shame Russians into becoming Europeans. See this city? You’re not worthy. You’ll foul it up. Moscow, as the political center, had more political samizdat. Leningrad’s was more literary. Of course, Russian people were always fighting the matrix of the city. It’s a matrix. It’s a grid. It best expressed the hatred of Russians toward city planning. It’s expressed by Pushkin in The Bronze Horseman. Why the hell did you build a city here? Where it would be absolutely doomed, repeatedly buffeted by the river? Destroyed, essentially? My grandparents met saving people during the great flood of 1924. The Bronze Horseman takes place in 1824, during the most disastrous flood in the city’s history. In both instances, lots of people died. In both instances, on downtown streets, water was at human height. My grandfather was a young organizer. She was helping older people. So the story of St. Petersburg is the story of people fighting the matrix, fighting the European, of people trying to fill all the spaces that were available to them with the rejection of the city. That’s Dostoyevsky, with his love and loathing for the city. But that’s only the core area. I grew up in the спальных районах (spalnykh rayonakh), the Krushchevilles. That’s the premise of the most famous Soviet comedy, Ирония судьбы (Ironiya sudbi). Everything was the same. But the unique St. Petersburg is probably one of the most literary cities that I can possibly imagine. Not because so many great writers lived there. It’s because it was essentially a literary project or a product of its own mythology.

A mythology about a city of basements.

And I belong to the generation of people who worked in those basements. I was a security guard in the Park of Culture, where I guarded the rollercoaster, called the “American Hills.” Many friends worked in boiler rooms. The memory from the story “Sentence” is of a gathering in a building slated for demolition. There are many hidden places in St. Petersburg. And, of course, there was always the KGB.

In “Flying Cranes,” your character comes across some workers in one of these hidden places. And they’re cursing so much. You depict that by using the English word “friggin,” a euphemism for “fucking.” Why?

I treated it like a game. It was like bleeping a word out. I kept writing “friggin.” It turns out that if you start substituting it everywhere, it becomes another layer of meaning. It’s like memory correcting itself, bleeping itself out. It feels like an act of self-censorship, which is basically what all writing in Russia was about. With samizdat, it’s all about self-censorship. An emigre writer said, “Well, at least back home the KGB used to read me.” No matter what inane story or stupid, drunken text, you could count on it being read by some guy sitting there, reading everything. Not with an eye to publish you but with an initial predisposition toward getting you in trouble. In some senses, it was not that different than a graduate student sitting there for $6 an hour reading the slush pile and thinking that it’s not your story that should be there but theirs. There is this guy sitting there and reading your text, and he wants to get you in trouble if you go over the line. So you don’t go over the line. So you learn to self-censor. But if you decide to be too cute, too circuitous, trying to outwit him by camouflaging your meaning, he will make sure you know that. “You think you’re so fucking smart.” So you self-censor. You know you can’t go over the line. Of course, it nonetheless wouldn’t have been like with my grandfather. We weren’t afraid of being arrested in most instances. You had to work really hard in order to get arrested. It would be because you were pointedly distributing banned books or something like that. They could send you a signal instead. A couple of guys might come and rough you up in front of your building. Or they would try to intimidate your parents, inform people where your parents work. You were fully at their disposal, at least physically. And if you didn’t get the message the first time, next time they would rough you up a little bit more so you would get the message.

I treated it like a game. It was like bleeping a word out. I kept writing “friggin.” It turns out that if you start substituting it everywhere, it becomes another layer of meaning. It’s like memory correcting itself, bleeping itself out. It feels like an act of self-censorship, which is basically what all writing in Russia was about. With samizdat, it’s all about self-censorship. An emigre writer said, “Well, at least back home the KGB used to read me.” No matter what inane story or stupid, drunken text, you could count on it being read by some guy sitting there, reading everything. Not with an eye to publish you but with an initial predisposition toward getting you in trouble. In some senses, it was not that different than a graduate student sitting there for $6 an hour reading the slush pile and thinking that it’s not your story that should be there but theirs. There is this guy sitting there and reading your text, and he wants to get you in trouble if you go over the line. So you don’t go over the line. So you learn to self-censor. But if you decide to be too cute, too circuitous, trying to outwit him by camouflaging your meaning, he will make sure you know that. “You think you’re so fucking smart.” So you self-censor. You know you can’t go over the line. Of course, it nonetheless wouldn’t have been like with my grandfather. We weren’t afraid of being arrested in most instances. You had to work really hard in order to get arrested. It would be because you were pointedly distributing banned books or something like that. They could send you a signal instead. A couple of guys might come and rough you up in front of your building. Or they would try to intimidate your parents, inform people where your parents work. You were fully at their disposal, at least physically. And if you didn’t get the message the first time, next time they would rough you up a little bit more so you would get the message.

So is that another reason why you switched to English? Because you had already gone through the practice of self-censorship with Russian?

It was a mechanical exercise almost to get my mind off of Russian. Russian is extremely willing to help you put yourself into a depression. It’s like “Sentence.” You start somewhere and then, three pages down the road, you’re asking, “How did I end up here in a whirlwind of dust?” I needed English to limit my ability to go off on tangents, to consign myself to a story, and contain myself within it. I can only be adequate to a sentence. One and the next…