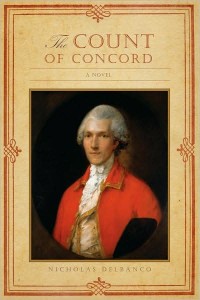

Nicholas Delbanco’s most recent novel, The Count of Concord (Dalkey Archive Press, 2008), tells the story of a fascinating historical figure, Count Rumford (1753-1814). Born Benjamin Thompson on a New England farm, Rumford climbs the social ladder of colonial Massachusetts, betrays his country, and travels the world. Seeking patrons among the nobility of Britain, Bavaria, and France, he is forced to flee each time a protector dies or falls into disfavor. A renaissance man, the count also performs experiments in heat, disproving the theory of phlogiston and making marked improvements to ovens, fireplaces, and chimneys.  He becomes a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, defends Munich from the Austrian and French armies, founds the Royal Academy in Britain, and, when he arrives in post-revolution Paris, is greeted by Napoleon. In The Count of Concord, Delbanco employs as narrator Rumford’s fictional descendent, 69-year-old romance author Sally Ormsby Thompson Robinson. Fascinated by her ancestor’s dramatic life, she explores the mixed motives and effects of his unending flight from obligation. Rumford-as-character is a complicated man, one who thrived in wartime, contributed greatly to the scientific community, and worked for the betterment of the poor yet constantly sought and prioritized his own advancement. Delbanco’s descriptions of the count’s lack of self-awareness and damaged legacies—the “by-blows” of nobility he leaves in his wake—serve to mute the heroism of Rumford’s epic life and amplify its tragedy.

He becomes a Count of the Holy Roman Empire, defends Munich from the Austrian and French armies, founds the Royal Academy in Britain, and, when he arrives in post-revolution Paris, is greeted by Napoleon. In The Count of Concord, Delbanco employs as narrator Rumford’s fictional descendent, 69-year-old romance author Sally Ormsby Thompson Robinson. Fascinated by her ancestor’s dramatic life, she explores the mixed motives and effects of his unending flight from obligation. Rumford-as-character is a complicated man, one who thrived in wartime, contributed greatly to the scientific community, and worked for the betterment of the poor yet constantly sought and prioritized his own advancement. Delbanco’s descriptions of the count’s lack of self-awareness and damaged legacies—the “by-blows” of nobility he leaves in his wake—serve to mute the heroism of Rumford’s epic life and amplify its tragedy.

This interview took place on November 12, 2008, in Ann Arbor, MI.

Brian Ralph Short: You picked this project up again after a considerable amount of time: how did that feel, and what was that revision process like? How much of the older draft stayed intact, and how much shifted with the addition of the narrator, Sally?

Nicholas Delbanco: I started this novel well over twenty years ago, doing the research, writing it, falling in love with it. That Michigan Quarterly Review piece [“Rumford, His Book”] came out a good decade ago, maybe more, so a long time passing, I worked on the life of Count Rumford and became, as it were, expert, and wholly versed in his history. But if I can back up for a minute: he was born in 1753, died in 1814. He pretty much spans what we think of as the Enlightenment and the beginning of the Romantic period. What that means in practical terms is that most of his life, he was one of those meliorists, one of those world-building, outward-facing, I-can-fix-the-lot-of-mankind types. I read thousands of pages of his essays, thousands of pages of his letters, and there was nothing that we would describe as remotely self-conscious or self-aware. Which is the sine qua non of the novel nowadays, and ever since the Romantic period, an absolute bedrock of what a book gets built on. There isn’t any character, unless the book be entirely comedic or satiric, who is central to a novel who has no self-awareness. And Rumford, it seemed to me, had none. So that’s finally the conundrum, or the thing that brought me up short. I had literally hundreds of pages of prose about this man, and no sense of what made him tick, or what made him behave the way he behaved in the world. And I could not get my mind around how to solve that within the context of an 18th century imitation, early 19th century. And so I just put it aside. It became dull and repetitive and one-trick pony-ish. And when one day I stumbled upon this notion of Sally, his invented tribesman, kinsman, and made her not merely self-conscious but able to think about him, I felt all the pieces fall into place and the key turn in the lock, because then I was able to opine about what Count Rumford represented without having him do so, because to have had him do so in his own voice would have been self-defeating. So the process of revision for me was the process of coming up with the idea of point-counterpoint and recognizing that I might be able to make a contemporary narrator, who is a sort of surrogate for the author, think about who Thompson had been and what he had represented. And then, when that happened, I cut quite a bit back from what had been an unwieldy, endless-seeming (laughs) novel about the 18th century. So the act of revision was twofold, the first was amplification—I wrote all the Sally chapters basically in a rush—and then of cutting back. And you will actually notice there are a few passages I couldn’t bear to entirely excise, where I have Sally say, ‘Well I wrote this, but it’s not good enough, so I’m throwing it out.’ The stuff for instance about Gouverneur Morris [on pages 271-272], you know, everything that’s in italics, it’s old Delbanco, which I’ve given to Sally to say it’s not good enough.

BRS: And what’s interesting about the Sally invention is, as I was reading it, it immediately threw me back to [the short story] “The Writers’ Trade,” where the children’s author throws his voice into the fireplace, right, this lovely scene, this interesting awareness of this child protagonist realizing that trick, latching on to it. And what I thought was so interesting about Sally, is that this is a double-throwing. You have Sally as the stand-in, but then she’s also taking on the role of the creator. You talked about writing the Sally pieces in a rush. Was it mostly molding Sally to the Rumford arc that you already had? Was there any molding the other way, of the story back to fit Sally?

ND: Mostly the former. I called it point-counterpoint. In some ways the less like her predecessor, the better, because that notion of the anti-self, or the contrapuntal voice, became valuable to me. I won’t pretend otherwise: a lot of what she did, I just took from my own experience. I owned the farm were she purports to have lived, though with her lesbian lover. I wrote that particular thesis while I was an undergraduate at Harvard, although I did not lose my virginity in the K entry of Winthrop House. I mean I was remembering being an undergraduate then and there. And I’ve lived, as you know, in New England, with its long, dark winters. So I found Sally rather easy to invent, particularly since she’s just sketched in. She’s a series of brushstrokes rather than a rounded portrait. I do want to tell you by the way, for the mere gossip of it, that scene which you flatteringly remember from “The Writer’s Trade,” is real. My parents had a friend who had escaped from Germany roughly the time they did, on a bicycle with his wife. He drew and she wrote. They did a series of children’s stories called Raffi the Giraffe, which I have a copy, and then one of Pretzel the Dog, which was a little more successful, and then they named their next character Curious George.

BRS: (laughs) Oh my goodness.

ND: Exactly. This was Hans Rey, H. A. Rey. By the time of the story I tell in that had come to pass, he was terrifically successful, obviously. Somebody who wore a cap on his head would drive him to our house, and I thought, my god, this funny old man. He was a lovely man, and he took me out into the garden a lot, taught me about the stars, he also wrote a book about the stars, but he was a shitty ventriloquist. (laughs) I mean really bad. And he would come into the living room and sit, (in a high-pitched voice) “Macky, it’s Curious George, I’m in the fireplace.” And I would stare at him with a seven-year old’s aghast sense of, this person earns a living doing that? I pilloried him, in that story. But in some ways it’s absolutely true, it’s when I thought, my god, you can throw your voice for a living. He certainly did. And a handsome one it was.

BRS: What an amazing story.

ND: (laughs) So back to Sally.

BRS: I wanted to ask about a passage, the Red Devil Thompson passage, where Thompson is in the colonies and he is fighting the war, and they take over the town and use the gravestones for ovens; there is desecration of the gravestones everywhere. And that echoes throughout, we keep coming back to this idea of the names [of the dead] being inscribed on the bread.

ND: This is true.

BRS: What’s it like when you find that kind of detail: do you know it’s gold immediately?

ND: Yes. It leaps out at you. It’s shocking. I don’t know if you read in today’s paper, the piece about Peter Matthiesssen and Killing Mr. Watson. This is a historical character that he found something about thirty years ago, and it just stayed with him. When I found out that Rumford baked bread on the tombstones of the colonists and tore down all the fence rails for kindling, so that the pigs and livestock would run free, I thought, my God. Now Abigail, to whom I ascribe his rage–meaning he becomes that avenging angel because of the desecration of his beautiful love, etcetera etcetera—she I invented. And you can probably tell that. Most of those are fictive moves. But the flat fact of how he behaved, in hunting them, is recorded in the history books. And, to the larger point, I was actually talking about him. A couple of days after my reading here [in Ann Arbor], I was in Chicago and did something somewhat similar at a humanities festival, and a woman came up to me afterwards, sort of scolding me for not talking at greater length about his scientific prowess and his history as chemist and physicist and what have you. She was a chemist. His career, and it’s not an inconsiderable one as scientist, has always been associated with heat, with fire and the controlling import of it. From the fireplaces to the understanding of the nature of transmission of heat, and his disproving of that ancient notion of phlogiston, etcetera, etcetera–all of that is what he’s known for in the history of science, and if you are a scientist you would know. Anyway, I took that and turned it into the old notion of the black magician, trafficking with flame. There’s even a suggestion in some necromantic manuals that you have to have human sacrifice before you fully earn your stripes as a magician. So I made heat his element, fire, and left earth, air, and water elsewhere.

BRS: What was so interesting about the scientific [aspect of the novel] is, it does feel, as we move through, that he leaves these scientific discoveries behind him. He is inventing things that are necessary for the time and then immediately moving on, and there is this constant shift from intrigue to intrigue, from lover to lover, from landscape to landscape, and the pace of the narrative feels very much like it is calling attention to this. There is a galloping pace, a sense of constant movement. We always see Rumford in motion, in carriage between place and place. How intentional was this?

ND: In part it was intentional, in part it was an acknowledgement of the form of the 18th-century novel, which was by and large picaresque. When you have a guy who travels as much as Rumford does, and covers as much ground as he did, in a sense, each of these chapters are self-sufficient episodes. And I do think that is probably a fair description of his life, as well. When he left America behind, he left it behind. When he left England and Germany, ditto. But I was quite conscious of shaping the chapters as if they were episodic and transitional. There are some books, as you know, that come full circle, or that insist on replicating in their last sections, something that happened in the opening. But that wasn’t true for him except as I imagined, in that long coda, where he recapitulates his life.

BRS: And that coda, what I take to be the climax, that chapter where everything is breaking apart structurally, everything is bleeding in and there is this sense of all these things that he has left undone rushing into his consciousness. In his old age and vulnerability, he is no longer capable of keeping all this stuff out. Was that from the earlier draft of the novel?

ND: Yes, and you know, you remind me of something I have not thought of before. If one can be reminded (laughs). Because you had flatteringly referred to “Everything,” that short story of mine [before the interview started]. I think, in some ways, this book, is a mirror or a version of [the story collection] The Writers’ Trade. It follows the same pattern, anyway. It’s not entirely an accident because I was working on them more or less at the same time. But yes, his randy youth, his official middle age, and then his entirely incompetent old age. It’s rather the same sequence, isn’t it? Maybe, indeed, unavoidably so. But I knew, maybe not from the start, but certainly when I got there, in terms of the writing, that I wanted him to be sitting in that house in Auteuil, completely hidebound and ill. It is not clear to me, not clear to the papers of the time or what biographies there are, what he actually died of. I suppose you would probably call it a stroke. You know, I’m older than he was, and not yet entirely incompetent (laughs). So he used up. He died, not young, but emptied. And that image of him sitting alone, I mean, I put him in the correct house. There was a statue, a copy of a Michelangelo in the garden. Astonishingly enough, his landlady had been one of Franklin’s inamorata in Paris. All of this is true. Exactly what was going on his mind, of course I have no way of knowing, and I allowed myself to imagine.

BRS: These mirrors to The Writers’ Trade are interesting because I wanted to ask you about the model of inventing something as you become obsessed with it, as the appetite for discovery arises, and then immediately moving on to whatever distracts you next—

ND: (laughs)

BRS: (laughs) I really identified with that, as a writer. I thought, yeah, that’s pretty much how it is. Do you feel like that’s a satisfactory model of the creative process, or am I trying to draw a 1-to-1 correlation where maybe it doesn’t totally exist.

ND: I’m not sure it totally exists, but I am compelled to acknowledge, as I said and you pointed out, albeit perhaps inadvertently, that this is a pattern that I seem to have enabled before, or followed before. I think Rumford in his chair in the house in Auteuil is really very similar to the old man in “Everything.” I did something of the same, actually, in a novel of mine called Old Scores, where I have the man in his dying moment, have an entire sonata of everything that went on before, a reprise of his long history. So it may be a move with which I am comfortable; it may also be a way of allaying future ghosts. But as a literary device, it strikes me as a pretty useful one, because, among other things, you know, by the time you are on page 450, there’s every reason to assume that the reader will have forgotten what was on page 45, and so you have that reprise.

BRS: This what-happened-last-week-on-Rumford kind of move.

ND: I mean, in its way, it’s like the drowning man whose life is reputed to flash before his eyes.

BRS: We get an “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge” kind of sense.

ND: Right.

BRS: So this reprise is useful in these practical ways, but is there something else there, in terms of judgment, maybe, that you’re interested in? Is this the only way for us, as secular novelists, to render actual judgment?

ND: Interesting. Well, you know, it’s easy for me to talk about what a son-of-a-bitch he was, and how thoughtless and self-absorbed and scandal-prone, serially unfaithful and all that. It’s pretty easy to dismiss him as a human being. In fact, I had a more-than-sinking fondness for him; I rather liked the old rogue. My own feeling is that the emotion I hope the last chapter engenders is one of compassion…and if not admiration, at least a certain—well, la crima hero is the best term I have for it, the tears of things. And I would like the reader to like him at the end, because he is more sinned against than sinning.

BRS: One of the things that I think gives real pleasure is, especially with the scenes in the poorhouse—and again, this is a discovery, something he seems philosophically invested in as well as committed to working out the practical day-to-day details—but again, there’s this distraction, there’s the Academy of Science and everything after it, and what was interesting to me was that, there was the desire to help, but there wasn’t a sentimental attachment to it.

ND: Right.

BRS: And that’s what is maybe bracing but also very refreshing about Rumford is that—and of course his selfishness is his own fault—but this lack of self-awareness feels very fresh.

ND: Artists almost by definition are inward-facing and prone to nostalgia, and self-conscious in ways I’ve discussed, but I’m not so sure that men of action or men of invention generally are. I don’t know that Rahm Emanuel, who is about to become White House Chief of Staff, is spending a lot of time pining for his years as an Illinois congressman, or for the job he held before that. You do move on. You go from pillar to post, as it were. By the way, the chapter about the poorhouse, probably more than any other, is in his literal language. He wrote an essay about solving the problems of the indigent and the beggars in Munich. And though I embroidered it a little bit, most of the descriptions of the poorhouse are verbatim.

BRS: What was the process of synching all of the research together? You’re drawing from his words specifically, and whenever you need to you break it open and fill in what needs to be filled, but—

ND: He has five volumes of essays. And I read them. The stuff that struck me as really noticeable, I simply copied. At a certain point, to be totally honest with you, I can no longer remember what I wrote and what I copied. I am my own plagiarist in this regard. It’s alright, it’s in the public domain. But there are some lines there that maybe I wrote and maybe he did.

BRS: Is that kind of fun? Reading it and not knowing?

ND: It’s wonderful fun. I’ll give you another example of a hot spot, like the names on the gravestones. I did read, at some point, I can’t remember when, that Sally, his actual daughter, did exactly as I say in the last sentence of the novel. She had two favorite charities, and she endowed them by bequest: one a home for parentless children, and one a home for the New Hampshire indigent insane. Any daughter who does that with the money that her daddy left her (laughs) has to have a story to tell.

About Nicholas Delbanco

Nicholas Delbanco has authored or edited more than twenty books, including Spring and Fall, The Martlet’s Tale, the Sherbrookes trilogy, What Remains, and two teaching texts, Fiction: Craft and Voice (with Alan Cheuse) and The Sincerest Form: Writing Fiction by Imitation. The recipient of a Guggenheim and two NEA fellowships, he is the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor of English at the University of Michigan, where he also directs the Hopwood Awards Program.

For Further Reading

Read excerpts from Delbanco’s work here, a story of his in Five Points, and articles in Harper’s, the L.A. Times, and the Boston Globe.