In the denouement of his 1985 novel Continental Drift, Russell Banks lays out a kind of manifesto:

Good cheer and mournfulness over lives other than our own, even wholly invented lives – no, especially wholly invented lives – deprive the world as it is of some of the greed it needs to be itself. Sabotage and subversion, then, are this book’s objectives. Go, my book, and help destroy the world as it is.

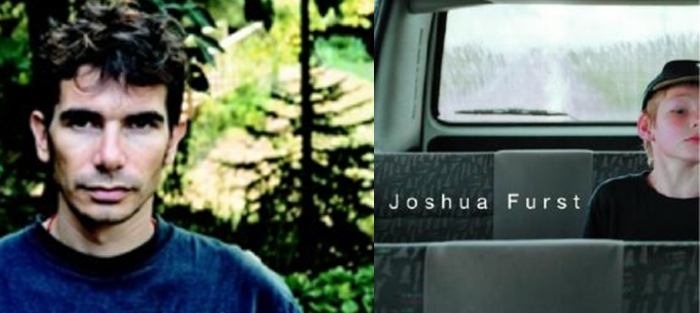

Few writers seem as concerned with the world as it is, and how fiction can explore its outer limits and shake those foundations to their core, than Joshua Furst. His debut story collection, Short People (Knopf), was one of those books that elicited an immediate vow to myself to read whatever Furst writes. The ten stories in that 2003 collection all deal with children, a.k.a. “short people,” and each one captures so fully what it feels like to be a particular age – 5 years old or 13 or any in between – that they generate the kind of false memories that only great storytellers can. After reading “Merit Badge,” Boy Scout Camp feels like something personally experienced. “She Rented Manhattan” will turn you into an awkward, lovelorn teenage girl for more than the story’s 16 pages.

In 2007, Furst followed up Short People with a novel, The Sabotage Café. That novel follows Cheryl, a suburban teen who runs away to Minneapolis, and her mother, Julia, beset by demons from her own past on the streets. Cheryl links up with a band of gutter punks, four guys who each reveal a particular shade of disenfranchisement with the American Dream. Trent, a darkly alluring anarchist, becomes her closest confidant. Julia houses alienation of a different kind; a past visit to a mental ward has made her suppress what she feels is her true self – until now. Their story takes a withering look at how society categorizes, and often ignores, the more difficult segments of a community. But Furst doesn’t deal exclusively with the dark side of consumerist culture, and those who rail against it. The Sabotage Café also maps the peculiar, sometimes hilarious, ticks of a generation raised in a pop cultural morass. Junk food to T.V., he gets the details very right, a kind of shorthand for childhood from the 1970s on.

Joshua Furst graduated from the Iowa Writers Workshop. He is the author of a story collection, Short People, and a novel, The Sabotage Café. Furst has received a Michener Fellowship, the Chicago Tribune‘s Nelson Algren Award, for the 1996 short story “Red Lobster”, the 2008 Grub Street Fiction Prize for The Sabotage Café, and fellowships from The MacDowell Colony and Ledig House. He has taught writing at several schools, including the University of Texas, Eugene Lang College, and, currently, the Pratt Institute.

Furst met me for lunch in Chelsea in late September. We talked about the launch of a new collective called Mischief + Mayhem, massively multi-player online role-playing games, the East Village in the late 1980s, and his belief that “every human being deserves the basic respect of being allowed to define their own reality.”

Interview

Lee Thomas: So, what made you want to become a writer?

Joshua Furst: When I was 8-years-old, maybe 9-years-old, I was cast as the boy in a production of Waiting for Godot at Ripon College in Ripon, Wisconsin. I spent the time during rehearsals studying the script and trying to parse some kind of cosmology out of the text. It put me in a relationship to words, and to aesthetics in general – theatrical aesthetics, in that case – that changed the way that I understood what it meant to be a thinking, feeling person in the world.

What did you read when you were growing up?

I read a lot of plays because I was very, very involved in the theater, and I was a child actor throughout my high school years. And I read a lot of comic books, and then the 10,000 Maniacs were very popular, and I became a fan of their “Jack Kerouac” song, so I searched out Jack Kerouac. I followed the sort of usual progressions through all of those writers whose books you steal, toward literature proper.

Do you come from a family of readers?

My parents are both serious readers. When I was a little kid my father, for bedtime stories, would read me Shakespeare plays, and we’d go a scene a night through the canon.

Do you have favorite plays?

Absolutely, you mean Shakespeare plays?

Yes.

Well, the one that I was most affected by, reading aloud with him, was Julius Caesar. But, by far, my favorite Shakespeare play is King Lear – which contains the entire world.

You studied at the Iowa Writers Workshop and sold Short People before you left the program, right?

I did. I sold it, I think, two days before I left town.

During what period had you written those stories?

Well, I’d been working pretty full time in theater, throughout my twenties in New York, writing and directing plays. Throughout that time I’d been writing stories, too, at my day job, instead of doing the work they were paying me for. So I had about half the stories in my collection before I went to Iowa, and I wrote about half the stories that became Short People while I was there. I knew exactly what I was trying to achieve before I got to Iowa, and went about writing stories specifically for the collection, and working toward this image I had in my head of how the collection would work.

Do you remember what the first story you wrote for the collection was?

The earliest story in the collection is “Red Lobster,” which was written in 1996, and published that very same year.

It won the Chicago Tribune Nelson Algren Award that year?

Yes, it won the award that year as well.

I love that story.

Good, I’m glad. That’s nice of you to say.

I also really love the first story in Short People, “The Age of Exploration,” and how it bookends the collection. It’s really a story about that awareness, when you’re a really little kid, of the way that you’re different from other people, and the dawning consciousness of other people’s interior lives. Is that something you thought about when you were a kid and revisited as a writer, or is that a fully adult idea?

I also really love the first story in Short People, “The Age of Exploration,” and how it bookends the collection. It’s really a story about that awareness, when you’re a really little kid, of the way that you’re different from other people, and the dawning consciousness of other people’s interior lives. Is that something you thought about when you were a kid and revisited as a writer, or is that a fully adult idea?

I mean, it’s definitely something I thought about as a kid. I think it’s impossible to be a kid and not think about, right? I mean, you know, the kid goes into the forest. What is going into the forest? Going into the forest is realizing that your family unit, your enclosed society is only a small part of a larger society, and that you’re now suddenly lost in this much bigger society, stuck in a terrifying position where you can’t understand the social codes because they’re so much more complicated and different from those of your small family unit. That can be a horrifying and troubling experience for any kid.

It can be a trauma from which you don’t recover.

Oh, I think it’s a trauma we spend most of the rest of our lives trying and failing to recover from.

In Short People, your young characters often strive to have agency in their world, and also to make sense of it. They aren’t really aided very much by adults. Is that search for meaning more prevalent in younger people? Or are adults just better at hiding their failed attempts?

When I was writing the book I wasn’t thinking of it so much in those terms – in terms of the relationship between the kids and the adults – as I was operating under a belief that I still hold, that there have been some major shifts in the way that our society operates: the prevalence of pop culture, and the way that pop culture has become an American culture. I think that there are certain generations of Americans for whom that was not the case. And I think for my generation, at least in my experience, the role that pop culture played in our understanding of morals and ethics and all of the things that go along with being a human being, was as large, or larger, depending on the situation, than the traditional cultures that we, as an immigrant society, have had handed down to us. So the mutts of America really do have a culture, it’s just a paltry and confusing and pitiless culture that our parents can’t help us with because our parents don’t live in that culture. They weren’t raised in that culture, and they didn’t have to grapple with the meaning of that culture in the way that we have.

What about the child narrator interests you?

There are a number of things about child narrators that interest me. One is, the relationship between preconceptions and experience. In that, as we become older, we become ideologues in certain ways. We start to believe that our beliefs about the world can define our reality. When in fact, that is obviously not true. Children are still impressionable enough to be testing out various belief systems. For them, the fault lines between ideology and realty become much more apparent much more quickly, to deeply intellectually-devastating effect. The other thing about child narrators that I hold to—that I think many writers who attempt to write from a child’s point of view don’t hold to, or don’t understand—is that there is not a difference in intelligence between a child and an adult. It’s not that children are naïve and incapable of discernment, it’s that children have less information, because they’ve had less time to compile information. I think we sell our children short, and we sell their experiences short, when we assume that they’re innocent in some way that they’re not.

In fact, I think a young person could read many of the stories in Short People and relate to them on a deep level. There seems to be an artificial construct in the world, that there’s a quantifiable thing called ‘adult content.’ If The Sabotage Café had contained less adult content, would you have been pressured to market the novel as Y.A.?

I wouldn’t have gotten that pressure because of my particular situation with my publisher, the set of circumstances around it. I’m lucky enough to have an editor who can still really do what he wants and pursue art. Obviously he’s affected by economic pressures, as anybody who works in publishing is, but he has a lot more leeway than a lot of editors do in our current environment. So he would have been able to get away with me writing about children for adults. I think in a different set of circumstances, with a different editor, absolutely, I would have been pressured to pander to the market. Also, interestingly, lot of stuff sold as adult fiction is, in fact, Y.A. fiction. A lot of coming-of-age novels aren’t measurably different from books that are marketed as Y.A. fiction. But separate from that, the difference between adult fiction and fiction for children has more to do with the point of view of the author and the subtleties of aesthetic and what those translate to in terms of the meaning that’s being communicated.

I wouldn’t have gotten that pressure because of my particular situation with my publisher, the set of circumstances around it. I’m lucky enough to have an editor who can still really do what he wants and pursue art. Obviously he’s affected by economic pressures, as anybody who works in publishing is, but he has a lot more leeway than a lot of editors do in our current environment. So he would have been able to get away with me writing about children for adults. I think in a different set of circumstances, with a different editor, absolutely, I would have been pressured to pander to the market. Also, interestingly, lot of stuff sold as adult fiction is, in fact, Y.A. fiction. A lot of coming-of-age novels aren’t measurably different from books that are marketed as Y.A. fiction. But separate from that, the difference between adult fiction and fiction for children has more to do with the point of view of the author and the subtleties of aesthetic and what those translate to in terms of the meaning that’s being communicated.

Pop culture is very prevalent in both your stories and your novel. It seems at times that you really drive the nail home with humor. Can you speak about humor in your writing?

Humor is very important to me. I believe that the best comedians are those who are most in touch with the darkness in themselves and their world. I’m conscious of that when I’m writing. How it appears in scene is less consciously within my control, because I have to write towards the reality of the characters and the situations if I’m going to make it believable. I do think that there is a certain amount of absurdity that is inherent in our contemporary world, that a lack of consciousness about this leads to a kind of a lie. And with that absurdity, obviously comes humor.

Are there comic or satirical novelists you enjoy reading?

I mean, my hero is Phillip Roth, who is often satirical. Though, not lightly satirical, like I would say Confederacy of Dunces is.

There’s no slapstick.

No, there’s a lot of slapstick in Portnoy’s Complaint, but it’s such gruesome and ugly slapstick, such self-loathing slapstick, that you’re never quite sure what the target it. Dostoyevsky – who’s another one of my huge heroes – is full of slapstick and comedy, too.

The Russians are really good at humor. They wrote such long works that they really could cram it all in. Talking more about Sabotage Café – a large part of the book deals with street kids and gutter punks. What made you interested in telling their story?

There are a number of things that made me interested in telling their story. I was fascinated by their particular relationship with American society, and the fault lines of American capital that their existence in and of itself points out. They, naively or not, have recognized one of the core injustices of American capital. And unlike most of the rest of us, they have attempted to find a way to grapple with it. They generally haven’t done a very good job of it. They generally end up destroying themselves more than they end up actually dealing with the problem. But to dismiss them out of hand for those bad choices becomes, I think, in our public conversation, a way of dismissing the truth behind those choices. Just because they’re wrong doesn’t make them wrong, you know?

One of the other reasons I was fascinated by them is because I lived down in the East Village during the late 1980s, early 90s, during the riots in Tompkins Square Park, and the entire transformation of that neighborhood. The culture of transgression was basically legislated out of the neighborhood, and the neighborhood was changed forever, obviously. So I had this storehouse of experience and memory that was fertile for a novel. There are a great many other reasons why I chose them, but these are the two primary inspirations.

Did you interact with the kids in your neighborhood?

You couldn’t not. When the streets close down and there’s a mob on the street, if you’re on the street, you become part of that mob. You have no choice.

My interactions with these kids in San Francisco always felt very us-versus-them tinged. I wish that they weren’t, but the barriers to dialogue seem so high. That feels like a cop-out on my part.

No, it’s not. The barriers to dialogue are insurmountable. We live in a culture in which identity is such a construct, in which everybody, at a certain point in their life, surrounds themselves with material signifiers of the person that they want the world to think of them as being. And there are so many varieties of choice there, and the meaning of those signifiers is so complex and so intertwined with consumerism and various approaches to consumerism and various relationships to class – both psychologically and materially – that nobody can really talk to each other. I mean, talking to those street kids if you’re a good, left-leaning, humanist urban dweller – which I’m assuming you are because you’re wearing a corduroy jacket – is just as impossible as talking to Glenn Beck or one of his followers. Every little group has its walls, and nobody can communicate outside those groups – at least superficially.

Between the recurring case studies in Short People and Julia, the mother in The Sabotage Café, you write very convincingly of mental illness. Do you have experience working in a hospital, or visiting a mental ward?

I know quite a bit about mental illness. I’ve thought very deeply and very long about the relationship between mental illness and the way that society conceives of itself, and the way that we define reality. One of the things that mental illness points toward is the possibility that reality is not what we think it is, and I believe that every human being deserves the basic respect of being allowed to define their own reality.

Julia really considers the compromises that she has made – basically sacrificing herself for a stability that feels more constraining over time. Many people play around the edges of those ideas and mostly keep it together, but I think that there is the Julia extreme and the Trent extreme – of anarchy and rage, even if that leads to self-destruction. Is there a happy compromise, or is that just something that people have to live with?

The Julia extreme being this nice suburban home?

Yes, the nice suburban home, keeping your demons at bay, and the implicit understanding that to participate in society you aren’t going to express yourself in certain ways, or people will think that you are mad.

Well, I mean, it’s hard to express them without people attempting to paint you as someone who is going to burn the house down. I think, separate from the aesthetics of the book and the issues of the characters, there are other possible ways to experience and engage in society than capitulation, having to do with defining society down, and thinking of community in terms of your neighborhood, your block, your town hall. The small society in which you operate has room for its own more equitable and less autocratic system. That, in the end, becomes more powerful than the larger organizational systems in some ways – if it really works, if you’re living and working within that environment. The very powerful forces in our society have learned a valuable lesson from the 1960s, which is that if they sell you back the image of what you want, they will neuter the dissent that you’re attempting to express. They allow you to receive the ego-gratification of your dissent, without ever having to grapple with the repercussions of that dissent. You feel heard, without actually having to be heard. And they can keep right on doing the corrupt and despicable things they’ve always been doing.

Does your experience in drama inform how you think about and write fiction?

Oh, absolutely. There are a number of ways in which that’s the case. For one thing, my understanding of dialogue and point of view and the relationship between words and meaning rose out of a deep engagement with the vernacular, the spoken word, because in the theater it’s all spoken. That’s had a deep effect on how I think about characters in a work of fiction. For another thing, because I started in theater, because I really came to literature through theater, my primary relationship with literature was completely international. In theater there’s not such a distinction being made between American playwrights and non-American playwrights. There are plays, and you read the history of theater, and you’re reading Brecht and Genet and all of these playwrights from around the world, as the history of theater – you’re not just reading English-language theater. I didn’t get a degree in English Literature, so from the start, I didn’t think of literature as this one English tradition, I thought of it as the whole history of words on a page. That would not have been the case if I hadn’t come out of the theater.

On another level, my approach to aesthetics has been very defined by working in theater. I have much less interest in, or tolerance for, pre-existing genre convention, because the particular kinds of things I was doing in theater had to do with character, space, and time, and all of the things that can be done within a fixed space. I think of a work of literature as being, in many ways, a fixed space of time, and what can be done within that. As opposed to, “How do I tell a social-realist story, about three generations of a family that touches on class and society?” in these various workman-like ways.

Do you still go to the theater?

I have lately been writing theater reviews for The Jewish Daily Forward, and that has gotten me into the theater more frequently than I’ve gone in the recent past. When I left theater, I left theater because I couldn’t play well with others. And I always felt like they were fucking with my vision. And then I didn’t enjoy going to theater because all I saw was compromise on the stage for a long time. But I have begun – now that I have less of an investment in theater and the way it works – begun to be able to appreciate it more again.

Do you ever write plays?

I’m talking to a friend of mine about maybe writing a one act. He’s going to write one too, and we’ll mount those together. But I haven’t seriously written a play since 1998.

In an Identity Theory interview from 2003, you spoke about going through a bit of hardship for the sake of your art – this idea that you have to earn it in order to teach yourself the meaning of trying to make your work the best it can be. When you teach, is that something you talk about with the students? Is that something you think can be taught?

What I can do as a teacher is give the students tools by which to read better, and understand on a theoretical level the relationship of their choices sentence-by-sentence to the effect of those choices on the reader. Then I can talk with them about the process by which one goes about teaching oneself. Now, the first part of that is difficult and is real, there are actual concrete things that the students learn in that context. But in terms of what happens afterwards, there are a few essential things that I think any writer has to do if they’re going to be a good writer. One is, they have to be able to make their own choices, as opposed to thinking first “What would my teacher think is the right choice?” And if their only experience with writing, and their only experience with literature has been contained within a classroom, they’re only going to know how to attempt to please the figure of authority in that classroom. So, until the only authority in the room is their own developing aesthetic, and the literature that they’re reading, they’re not going to be able to define these things for themselves. I tell students not to go to grad school straight out of undergrad, because it’s going to be catastrophic for them as writers. But it’s not because I believe they should live in hardship, it’s because I think that then, if and when they choose to go to grad school, they’ll be going on their own terms, instead of someone else’s terms, and they’ll be better writers for it.

You teach undergraduates?

I teach undergraduates, primarily. I enjoy teaching undergraduates, because the flip side of what I’ve just said is that with graduate students, you’ve often got people who have so clearly defined their aesthetic that they’re not willing to engage in the conversation on my terms, which I, of course, want to do.

Your new novella: you only have to say what you want about it.

No, no. It’s finished. We’re shopping it. It’s called One Inch Tall. It’s about 80-85 pages long. It’s a story that revolves around a 40-ish-year-old man who, for a variety of reasons, is obsessed with, and whose life has been overtaken by, massively multi-player online role-playing games.

Did you do research for this?

Ah, I plead the fifth.

In late September you had a big launch party for Mischief + Mayhem – talk to me about the genesis of this idea.

Mischief + Mayhem started as a collective about three years ago. It was just a group of writers who, to one degree or another, had all experienced quite a bit of success in the publishing world and artistically as writers, who were seeing the trends going on in publishing and in literature, and in various ways and to varying degrees were dissatisfied with these trends. The history of literature is littered with small bands of people who have united for aesthetic reasons and attempted to support themselves and each other as artists, without having to bend to the marketplace at every turn. So that’s what we have set out to try to do.

Mischief + Mayhem started as a collective about three years ago. It was just a group of writers who, to one degree or another, had all experienced quite a bit of success in the publishing world and artistically as writers, who were seeing the trends going on in publishing and in literature, and in various ways and to varying degrees were dissatisfied with these trends. The history of literature is littered with small bands of people who have united for aesthetic reasons and attempted to support themselves and each other as artists, without having to bend to the marketplace at every turn. So that’s what we have set out to try to do.

How did you find each other?

Interestingly, we had all, at some point, over the past ten years been to the same writers’ colony, which is called Ledig House – it’s in Upstate New York. So we all met through the network of people who are alumni of Ledig House.

Part of Mischief + Mayhem’s mission is to “Nurture and promote distinctive authorial voices, especially those that fall outside commercially acceptable notions of literature, and to do everything we can to bring those writers the largest possible audience.” How do you find manuscripts that fit this bill?

We don’t really take submissions, because there are only five of us, and we’re all working writers. What we are open to are queries about our process and how we’ve gone about building this, in hopes of helping other people form their own collectives, and their own groups, and continuing to open up the dialogue. Which isn’t to say we only publish ourselves, we’re explicitly not interested in only publishing ourselves. I, for instance, have nothing planned in terms of the near future, in terms of publishing with Mischief + Mayhem. I’m under contract with Knopf, and I’m very happy with my position being published with Knopf. I just know of a great many authors who are not as lucky as I have been, and who are not in the position that I’m in, who are doing extremely interesting things in kind of a punishing environment right now. It’s kind of a ripple effect: everybody knows somebody who knows somebody who knows somebody who’s written a great book. That doesn’t mean that we’re a closed system that is only interested in publishing the elite people who have already made it, but because it’s not our full time job, there’s no way that we can read manuscripts all day.

Is the primary goal to open up a dialogue online?

Well, one aspect of what we’re doing right now, as we’re launching the press, is a website that has a blog component and the journal component. Once a month there’s a journal called Wild Rag that will publish four things, a piece of fiction, an essay, a piece of criticism, some sort of visual art and another thing that might be a hodgepodge of any of them, or might be something completely different. The first one of those is launching, we’re shooting for October 1. Then there’s a blog, which we’ve started posting to. We haven’t yet worked out all the kinks. That will have new posts—when it gets going—every day, by the members of the collective themselves, as well as other bloggers and other artists in various art forms, writers who are interested in visual arts, and specifically in translation, and a variety of other things, writers who are kindred spirits of ours. So every day there will be new content. Hopefully it will dissect and engage with ideas of aesthetics and art in relation to politics and culture, and with the question, “What does it mean to try to create relevant art? Is it possible for art to actually be relevant, or are we speaking in a vacuum?”

Well, one aspect of what we’re doing right now, as we’re launching the press, is a website that has a blog component and the journal component. Once a month there’s a journal called Wild Rag that will publish four things, a piece of fiction, an essay, a piece of criticism, some sort of visual art and another thing that might be a hodgepodge of any of them, or might be something completely different. The first one of those is launching, we’re shooting for October 1. Then there’s a blog, which we’ve started posting to. We haven’t yet worked out all the kinks. That will have new posts—when it gets going—every day, by the members of the collective themselves, as well as other bloggers and other artists in various art forms, writers who are interested in visual arts, and specifically in translation, and a variety of other things, writers who are kindred spirits of ours. So every day there will be new content. Hopefully it will dissect and engage with ideas of aesthetics and art in relation to politics and culture, and with the question, “What does it mean to try to create relevant art? Is it possible for art to actually be relevant, or are we speaking in a vacuum?”

How do you decide what art you engage with?

I get a lot of it from my students, who don’t know any better, or haven’t been trained to know any better, and so just pick up any book that’s before them. They mention these oddball and exciting writers they’re reading, and I write down the name of the author and look it up, you know? Then, also, I know the terrain a little bit, and I’ve read widely enough that there are authors whose work I’m following, and when their next book comes out, I know I want to read it. There are certain people who are affiliated with certain aesthetic movements that I find fascinating, so I will say, Oh I want to look at this because of this, that or the other criterion. If you’re engaged with your world, your world engages with you. I don’t find what I want to read from the New York Times.

Do you think there is a difference between being involved in the art of your contemporaries and art more generally speaking?

I pretty militantly read one non-contemporary book for every contemporary book I read. I try to make sure, if I’m reading a Charles Dickens book, the next book I’m going to read is going to be a contemporary book. And if I’m reading a contemporary book, the next book will be a non-contemporary book. To me, the best contemporary literature is in conversation with the history of literature, as well as the literature that exists in our singular time and place. And then, of course, it’s also in vigorous, fierce conversation with the world around us, too.