The story goes that when Émile Zola began research for Germinal, his masterpiece about the nineteenth-century French miners’ revolution, he toured the working mines firsthand. He noticed a broad, muscled Percheron pulling a sled through a tunnel. The foreman explained that they brought the horses down as foals. Yet when Zola asked him how they got them in and out of the mines each day, the foreman responded that they didn’t: “He hauls coal down here until he can’t anymore, and then he dies down here, and his bones are buried down here.” This was the seed for Zola. His descriptions of the mine horses in Germinal shed light on the harsh treatment of all workers, whether human or animal, and lend a concretized pathos to the majestic narrative rail against worker exploitation.

It’s a similar case in Christina Baker Kline’s new novel, The Exiles (HarperCollins), which might be understood as literary historical fiction with a feminist slant: within a depiction of the history of British convicts sent to Australia (marginalized people already), Baker Kline represents women’s experience, and within women’s experience those who left few traces: an indigenous girl, an orphaned young woman with neither financial means nor practical skills, and the fatherless teenage daughter of a drunken midwife. The three protagonists are of the margins within the margins—people whose stories were unrecorded, and so have gone untold.

Baker Kline’s storytelling reads so effortlessly and true that it’s easy to overlook the painstaking research that went into this novel, and the careful balance between vivid detail and larger questions about these women’s human experience. But let’s be clear: The Exiles is a masterful high-wire act. As both writer and reader, it’s thrilling to read.

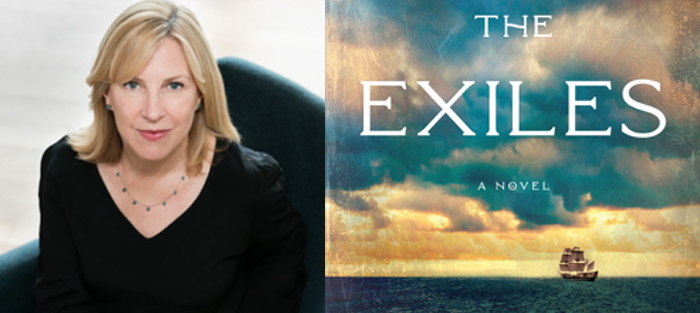

The Exiles is Christina’s eighth novel. Her work has been published in over forty countries, and her novels have received the New England Prize for Fiction, the Maine Literary Award, and a Barnes & Noble Discover Award, among other prizes, and have been chosen by hundreds of communities, universities, and schools as “One Book, One Read” selections. Her essays, articles, and reviews have appeared in publications such as the New York Times and the NYT Book Review, The Boston Globe, The San Francisco Chronicle, LitHub, Psychology Today, and Salon. She is a graduate of Yale, Cambridge, and the University of Virginia M.F.A. program, where she was a Hoyns Fellow in Fiction Writing. She is an Artist-Mentor for StudioDuke at Duke University and the BookEnds program at Stony Brook University, where, as a Fellow, I was so lucky to work with her.

Interview:

Jennifer Solheim: In discussing the fictionalization of historical events in my novel, you quoted Emily Dickinson: “tell all the truth but tell it slant.” But as an edict, the Dickinson line isn’t only about recuperation or new perspectives: it’s also about character and the particularities of individual experience. So how did you work with the idea of telling truth at a slant in The Exiles?

Christina Baker Kline: You’re right; it’s about both things. The next line of the Dickinson poem is “Success in circuit lies.” I kept thinking about this as I wrote The Exiles: how could I approach the story in roundabout ways to make it more intimate, more engaging, less like a rote history lesson? There’s a danger, when you write novels that involve large amounts of research, of sounding didactic, or worse, dry. In ways large and small, the task of a novelist who writes about the past is to make it come to life, to find singular details that make the story breathe.

Christina Baker Kline: You’re right; it’s about both things. The next line of the Dickinson poem is “Success in circuit lies.” I kept thinking about this as I wrote The Exiles: how could I approach the story in roundabout ways to make it more intimate, more engaging, less like a rote history lesson? There’s a danger, when you write novels that involve large amounts of research, of sounding didactic, or worse, dry. In ways large and small, the task of a novelist who writes about the past is to make it come to life, to find singular details that make the story breathe.

In The Exiles, I use a secondary character, bawdy, irreverent Olive, to recount the British plan to transport poor women to Australia as breeders. Her wry humor is a useful delivery system for this kind of exposition.

In general, my version of 1840s Australia is a blend of then and now. While I worked hard to avoid blatantly anachronistic language in dialogue, I didn’t try to approximate the speech of the time. I wanted the book to feel contemporary. I wanted readers to feel as if they were immersed in that world.

You traveled to England, Scotland, and Australia to research The Exiles. How did research and character development work in this novel? Did one inspire the other?

Some novelists don’t travel for research; they believe that imagination is all you need, and maybe they’re right. But I find standing on the soil where my novel takes place incredibly inspiring. If I hadn’t gone to Tasmania I wouldn’t have known about the fluorescent orange lichen on the rocks of Mount Wellington, for example, or that wallabies gather by the hundreds on the outskirts of the city of Hobart at dusk. I wouldn’t have known what the four-mile trek from the harbor to the Cascades Female Factory was like, or what it felt like to be inside the walls of that prison. I was in Scotland for a week and Glasgow for only a few days, but several months later, as I was describing Hazel’s miserable life there, I could easily envision her making her way along the wynds and pilfering a silver spoon from a shop; I knew what the cobbles felt like under my shoes. Her flinty character was forged during that visit.

Your three main characters meet by chance and fate, in some ways—but they also encounter one another as a result of the cruelty of systems and individuals to which they are subject. How did you develop these three characters and bring them together in the story?

The constantly changing relationships among these women are at the heart of this novel. Without them, the book would be little more than a treatise on the systematic oppression of women and Aboriginal people by the British government.

I think of Evangeline–the book-smart but naïve daughter of a village vicar who finds herself accused of murder and sent on a repurposed slaving ship to Australia–as a stand-in for the reader. She is catapulted from a comfortable middle-class existence into a world she’d never imagined; each experience is a fresh shock. Hazel and Olive, the convict women she befriends on the ship, are accustomed to this kind of life, more tolerant of its indignities and outrages. Mathinna, an Aboriginal girl, is torn from her home and family and must figure out how to navigate life in a household filled with uncaring British aristocrats. Hazel, working as a maid in the governor’s house where Mathinna lives, is the only person who shows her genuine affection.

An Aboriginal girl dependent upon a British aristocrat’s wife and amateur anthropologist, Mathinna is ultimately granted even fewer rights than the convicts. How did you approach writing Mathinna and her story? What inspired you to include her as part of the story of the convicts?

When I conceived of this novel, I planned to write about the British convict women exiled to Australia. But the more I read about the period, the more convinced I became that it would be irresponsible not to address the history of the Aboriginal people who lived on the island of Tasmania for thousands of years before being exiled by the British. I read the real-life story of Mathinna, the orphaned daughter of a chieftain who was taken on a whim and later abandoned by the British governor and his wife, and knew that she needed to be part of this story. It’s complicated to write about real people whose lives ended long ago, their fates solidified. As I did in my previous novel, A Piece of the World, I chose to end Mathinna’s story with a moment of connection, of recognition. Like Mathinna’s, the final years of Christina Olson, the real-life person who inspired that novel, were bleak. I wanted to end the stories from Mathinna’s and Christina’s perspectives by highlighting their resilience as well as their vulnerability while they contended with forces beyond their control.

When I conceived of this novel, I planned to write about the British convict women exiled to Australia. But the more I read about the period, the more convinced I became that it would be irresponsible not to address the history of the Aboriginal people who lived on the island of Tasmania for thousands of years before being exiled by the British. I read the real-life story of Mathinna, the orphaned daughter of a chieftain who was taken on a whim and later abandoned by the British governor and his wife, and knew that she needed to be part of this story. It’s complicated to write about real people whose lives ended long ago, their fates solidified. As I did in my previous novel, A Piece of the World, I chose to end Mathinna’s story with a moment of connection, of recognition. Like Mathinna’s, the final years of Christina Olson, the real-life person who inspired that novel, were bleak. I wanted to end the stories from Mathinna’s and Christina’s perspectives by highlighting their resilience as well as their vulnerability while they contended with forces beyond their control.

I’ve always admired the way your characters inhabit their bodies. I think of the bitter cold in the harrowing scene in Orphan Train when preteen heroine Dorothy traverses four miles through a snowy winter night in Minnesota, or of Christina’s pleasure in bathing before meeting her paramour in A Piece of the World. Now, in The Exiles, there are vivid descriptions throughout of the female body’s survival against horrifying conditions—the convicts are granted only slightly better conditions than the enslaved Africans who crossed the ocean in the very same ship hold, before the abolition of slavery. How do you approach embodying your characters as you write?

When I’m writing a book set in the past, I get completely obsessed with contemporaneous first-person narratives. While writing Orphan Train, I found a slim memoir at the Heartland Museum in Fargo, North Dakota, titled Rachel Calof’s Story: Jewish Homesteader on the Northern Plains. It’s filled with hard-to-believe details about what it was like to live through Midwestern winters in the 1900s. For The Exiles, I read ship surgeons’ logs, letters from female convicts, and newspaper articles from the 1800s about conditions on the ships.

But I understand that your question is larger than that. I work hard to convey the physical details of my characters’ lives, because I know that in order for a book to sing it needs to be fully felt in the body. Physical trials teach us what we can endure, what our limits are. We remember them vividly. Evangeline’s journey to the (literal) underworld of Newgate Prison and the bowels of the ship is horrifying, yes, but it is filled with self-discovery.

Newgate no longer exists, but I visited the prison site in London and similar historic sites in England and Australia. I also drew on my own life experiences; years ago I taught at a jail in Maine and a women’s prison in New Jersey.

I’d like to conclude with a question for fiction writers about the research and writing of historical fiction that portray brutal realities, as you have done so movingly in The Exiles: how do we stay true to the tales we tell while also giving them life beyond the margins?

The lives of the convict women in the early-to-mid eighteenth century were indeed brutal and unfair. It was even worse for the Aboriginal people. I didn’t want to minimize the hardship, but I was determined to celebrate the women’s victories, large and small. Though only one of the three main characters ultimately thrives, many of the minor characters–including Olive!–find ways to forge a life in this strange new land. They are the foremothers of the Australia we know today.