The Illness Lesson (Doubleday) is a psychological thriller that unravels the layers of women’s repression and rage. It’s subtle in its warnings that women are always more complicated than the men around them assume. Set in the 19th century, the book chronicles the story of Samuel Hood, his male colleague, and his daughter Caroline as they found a school that promises a revolutionary education for women. Caroline has concerns immediately which the men dismiss. When a flock of red birds arrives in the town, the town and the school are unsettled. Suddenly the students suffer mysterious rashes, headaches, and seizures as they often wander off into the night. A physician is brought in but his cure is worse than the illness. Caroline’s own body breaks down, and she must confront the patriarchal forces that have raised her. In the end, it is the men’s assumptions of how simple the education of young women will be that leads to their failure.

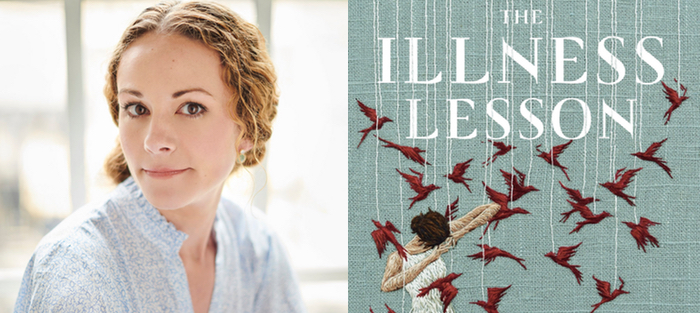

Clare Beams’ story collection, We Show What We Have Learned, was published in 2016 by Lookout Books. It won the Bard Fiction Prize, was longlisted for the Story Prize, and was a finalist for the PEN/Robert W, Bingham Prize, the New York Public Library’s Young Lions Fiction Award, and the Shirley Jackson Award. The Illness Lesson, published in February, is her first novel.

Clare and I met up at Founding Farmers in Washington, DC for brunch and bottomless coffee the morning after her stop at Politics & Prose Bookstore. Neither of us knew then that the rest of her book tour would be cancelled days later due to the pandemic.

Interview:

The Illness Lesson is set in the 1870s. How do you think readers receive a character of this era like Caroline? Can we sustain patience with her restraint?

Caroline has had a unique education that has made it difficult for her to act. Her education was built on her father’s judgement, meaning if her judgement conflicts with his, she should trust her father’s. Maybe it’s her lack of agency that can sometimes frustrate today’s reader who desire women to be bolder—though I think she does get there, in the end.

By contrast, Sophia speaks her mind and seems more self-determining.

Sophia, David’s wife, has a different mind and sense than Caroline. She isn’t as educated as Caroline is in some ways, but she has lived through things that Caroline has not, so her vantage is differently informed. She has more initial agency than Caroline’s careful upbringing allows, but this book is Caroline’s story.

Did you consider other voices besides Caroline’s in terms of point of view?

In early drafts I considered telling three different stories set during three different time periods all at the School of the Trilling Heart. But once I was writing, I was only interested in the outcome of the 1870s. I realized this school wouldn’t survive.

In early drafts I considered telling three different stories set during three different time periods all at the School of the Trilling Heart. But once I was writing, I was only interested in the outcome of the 1870s. I realized this school wouldn’t survive.

Speaking of survival, Eliza is a force. She’s so brassy and manipulative. It’s a pleasure to read her, and we learn so much about Caroline through watching her react to Eliza’s fits.

Part of Eliza’s tragedy is her inscrutability. If you could see inside her, she might not have been so lost.

The men in the novel seem to want to save the woman through education. Is that fair?

The principle of their education is beautiful: the idea that women can do what men can do.

But the school is more about that principle than it is about the girls at this school. I think no space has been left for the girls, really. It’s not that the principles are wrong. It’s that they are being implemented with these blind spots just because the things these men are choosing not to look at are complicating what they’re trying to do. There’s this sort of beautiful principle that has no attachment to the rest of the girls’ life.

How does the principle conflict with reality?

These girls’ world is not going to treat women as if they were just minds. So, it’s not that the principles are wrong, it’s that they’re not as simple as the men are pretending.

You use dreams at key points in the narrative. They are vivid and necessary for what they reveal about the characters. I’m curious as a writer about your role of using dreams in the book.

The dreams are a way for the repressed parts of Caroline to come out; they don’t want to stay silent, so I think that’s a way for those parts of her to have a voice. There is so much of Caroline that she herself is not aware of, things that her father has never acknowledged, mostly sexual, because in some ways she’s living a child’s life as a twenty-nine-year-old woman.

You’re saying the narrative has to exist with and without the dream.

Absolutely. If there is a dream in fiction, you need to know it’s a dream, relatively quickly, and you also need to still care about what’s happening in it when you realize it’s a dream.

Talk a little bit about Samuel. He seems to sometimes avoid parenting by using philosophy, but also in many ways he is a loving devoted father.

I still love him at the end, even though that’s not everyone’s reaction to him, and I’m not sure it’s really the right reaction. I do think he’s ultimately the villain in the book, despite his redeeming qualities. Hawkins is like walking evil. But Hawkins is only able to do damage because Samuel lets him in.

A female Samuel would not have been able to exist; she wouldn’t have been permitted the same blind spots. Samuel feels tragically alone, but it’s still in this kind of liberated way.

Are we ever aware of our own blind spots? When you read something do you operate differently than you think a man would?

I do think I operate differently, in just about every space, you know. I was one of those people who, until I was out of college, would probably have told you that we didn’t really need feminism anymore—that nothing had been harder for me. Then you grow up and you’re like, “Huh, some of these things are not the same.”

It’s like the water you’re swimming in all the time; you just don’t see it all the time.

Talk a little bit about magical realism—like the use of it especially in your story collection. Do you always write magical realism?

It’s mixed. I would say some of the stories in the collection aren’t exactly magical realism. Sometimes the strangeness is more pronounced than others, but to me there’s still always something that’s odd. I love this area between realism and surrealism, and I love that it keeps shifting.

I can’t wait for your next book, Clare. What are you working on now?

My next idea is still in its early stages, but it has its jumping-off point in a drug given to women from the 1930s to the 1970s called DES that was invented by a husband and wife medical team. DES was designed to prevent recurrent miscarriages. The idea was to regulate women’s bodies because they’d discovered hormonal swings and wanted to flatten out the fluctuations. It turned out eventually that DES caused horrible birth defects, especially in the female children.

What led to your research on this drug?

I found it when I was researching alternative titles for The Illness Lesson. I got lost in every weird medical corner of the Internet I could find connected to women’s health in any way.

I’m not the kind of historical writer who takes an event or a thing and tries to factually inhabit it. But I love to take the germ of something and pull it in a weird direction.