Today as I was scouring the morning news, I stumbled over the following headline: “A soldier needed an ear transplant. Doctors grew a new one in her arm.” The accompanying picture—an outstretched arm, the shadow of an ear pushing through the skin at the elbow—makes me wince a little every time I look at it. And I can’t help but wonder: What’s a good fabulist to do when every day the world offers as reality, posits as entirely normal, the surreal images of our nightmares?

Today as I was scouring the morning news, I stumbled over the following headline: “A soldier needed an ear transplant. Doctors grew a new one in her arm.” The accompanying picture—an outstretched arm, the shadow of an ear pushing through the skin at the elbow—makes me wince a little every time I look at it. And I can’t help but wonder: What’s a good fabulist to do when every day the world offers as reality, posits as entirely normal, the surreal images of our nightmares?

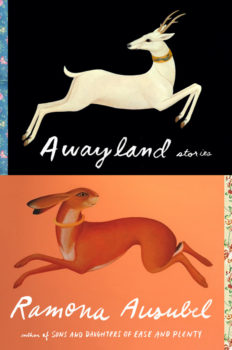

Ramona Ausubel’s dazzling new short story collection Awayland (Riverhead) provides reader and writer alike a possible direction. The eleven stories feel ripped out of a twisted fairy tales anthology: a cyclops posts his dating profile; a mermaid lures three shipwrecked sailors to their deaths; an aging mother evaporates; a young husband, in a romantic gesture to his wife, has his hand amputated and replaced with hers. The settings are all suitably fantasy-exotic—Beirut, a dying American town in the Midwest, a biosphere, an unnamed tropical island, a theme park that recreates Greek and Roman myths—and catalogued into sections with playful titles such as “Bay of Hungers” or “The Cape of Persistent Hope.”

Ausubel’s prose is pared down to a children’s book simplicity that matches these seemingly whimsical plots. Her sentences are lean and precise, honing in on the exact right image. Take this passage from “Fresh Water from the Sea”:

The girl watched boys jump from the sea wall into the deep blue. Families had chairs set up along the boardwalk, lunches, hookahs, children with candy-suck faces. They were alive and together and God, whichever god was theirs, had shaken this day out like a crisp sheet for them to lie down on.

The settings are all rendered with minimalistic detail, pared down to seem almost interchangeable. Here is the description of the Minnesota town in “Template for a Proclamation to Save the Species:

The economy droops. Winter is nigh. He takes solace in the fact that the whole city seems to have reached the sloppy bottom place, has sunk to the pond-scummy floor . . .

In the next story, “Mother Land” the unnamed country is rendered in a few sentences from the point of view of its just recently arrived American protagonist:

Lucy looked out the window. Women in patterned cloth skirts, men in jeans. Everywhere brightly colored plastic tubs in stacks. Children played in a red dirt field wearing their navy-and-white uniforms.

In fact, these stories are so deceptively simple and spare, about a quarter of the way through, I closed the book and thought to myself, is this really it?

But as I continued to read I realized Ausubel’s fabulism was not the mythmaking sort practiced by Kelly Link and Shirley Jackson but more closely akin to Voltaire and his satirical novel Candide. Like the titular protagonist of Voltaire’s novel, Ausubel’s protagonists—almost all straight, white, and callow—lead privileged lives, unable to comprehend the world’s cruelty outside the frame of their solipsism. Take for example the very next lines of the above description from “Mother Land.” The ironically named Lucy isn’t sure how to code the generic African landscape she’s just taken in: “Are they poor? she wanted to ask the African. Where should she set her sorry-gauge? The people looked clean and tended to.” The essential plot of “Mother Land”—an American woman falls in love with a wealthy and powerful white African and moves to his homeland where she leads a cossetted life on his colonial estate—is enough to make any minimally socially aware reader slightly queasy. But this is satire—not romance—and Ausubel never lets Lucy off the hook. The white African’s desire for Lucy appears to stem not from love but from his ability to control her given her foreignness and naiveté. Lucy gradually recognizes that her Americanness, and her whiteness, doesn’t render her powerful but invisible to the people around her. In the climactic scene of the story, Lucy convinces herself she’s going to die when the bus she and her husband are riding is attacked by an angry mob. The scene comes to an anticlimactic end, though, when the husband takes Lucy’s hand and the mob parts way for them. Lucy’s one quick perception: the rioters let her pass because she is “meaningless.”

The couples in “Template for a Proclamation to Save the Species” become pregnant and bear children solely to win a prize—a new car. The protagonist of “Departure Lounge” overcomes her qualms about flying to India and using an Indian woman as a surrogate mother in a single sentence: “I had two thoughts which arrived at the exact same instant: This is not OK and We will do this.“ She never questions the act again. When the wife of the protagonist in the story “Remedy” discovers that the bargain she is forcing her husband to make is inconveniently prohibited by American law, she finds an impoverished foreign island where her demand will be met. Just when the selfishness and egoism of all these characters begins to feel oppressive, Ausubel does give us one, small moment of grace. The young protagonist of “Club Zeus” starts of just as callow but this time his encounter with death and grief results in a moment of compassion between him and two foreigners. Perhaps youth might save us?

Ausubel’s satire isn’t didactic, and she offers no solutions. It isn’t a neat surgical evisceration. It is—like the surprisingly satisfying demise of a rapist in the final story—death by a thousand cuts. In the end, Awayland is the fabulist short story collection America deserves in the moment when we find ourselves gripped in another fabulist’s narcissism, slowly evaporating, being rendered nothing more than a blip in the world’s weather.