The former newspaper reporter in me demands I begin my thought here on Richard Ford’s new novel Canada (Ecco) with a bit of full-disclosure: Ford lives here in my native state of Maine and is a friend.

The former newspaper reporter in me demands I begin my thought here on Richard Ford’s new novel Canada (Ecco) with a bit of full-disclosure: Ford lives here in my native state of Maine and is a friend.

More full-disclosure: that last sentence seems so wonderfully odd to me, as I am a thirty-seven-year-old man still very in touch with his seventeen-year-old self who read Ford and his pals Raymond Carver and Tobias Wolff and believed they were the giants of contemporary American fiction. Two decades and many books later, I can’t say my opinion has changed much: Ford’s Canada is only further validation that I was right about at least one thing when I was seventeen.

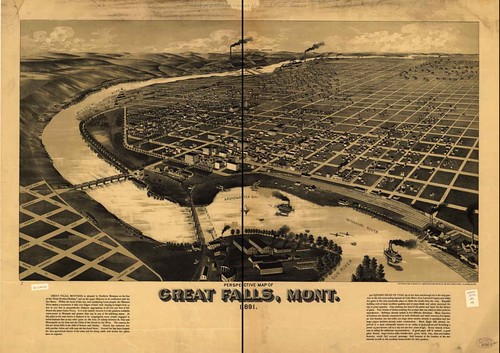

Ford’s new novel—his first since closing the Frank Bascombe trilogy that began with The Sportswriter (1986), earned the Pulitzer and PEN/Faulkner for Independence Day (1995), and wrapped with The Lay of the Land (2006)—finds the author returning to the landscapes and themes that made me fall in love with his prose: a combination of Montana and great upheaval during one’s teenage years.

But make no mistake, Canada is not an elder statesman of American letters repeating himself.

While Ford’s reputation stands in many ways on his Bascombe novels, it was actually his other books and stories that first cast their nets over me. Something about the stark geography of the stories in Ford’s Rock Springs (1987) seemed so perfectly harmonized with the spare prose. I’ve read and re-read it over the years. That collection is shot through with narrators not unlike the Canada narrator Dell Parsons, a man in his sixties looking back at his fifteen-year-old self. In particular, Rock Springs features Les, the narrator of the collection’s celebrated and oft-anthologized final story, “Communist.”

Ford followed Rock Springs with his quietly powerful novel Wildlife (1990). The short novel is narrated by Joe Brinson, a man approaching middle age but reminiscing and searching to make sense of the year he turned sixteen, when a wildfire swept through Montana and his family exploded.

Finally, there is Lawrence, the seventeen-year-old narrator of “Jealous,” the middle novella in Ford’s largely underrated novella trio, Women with Men: Three Stories (1997). Marooned in a barren landscape of endless wheat fields with his father, young Lawrence struggles to comprehend his parent’s separation.

“Well, I am a comer-backer,” Ford recently quipped in a New York Time Book Review podcast interview about Canada. He believed he was done with and would not return to writing about Great Falls, Montana. But as the landscape and themes continued to interest him, he wondered if he couldn’t “stand on the shoulders” of his previous work and “find something better.” Find something he has. Canada is unarguably Ford’s most fully realized and successful foray into his exploration of children in upheaval and children dealing with the bad decisions of adults. The theme of adolescence knocked off the rails, and the consequences that follow, runs through Canada with the power and certitude of one of Montana’s many wild rivers—yet, Ford manages it without repeating himself and as a more mature author working at the height of his powers.

In the broadest strokes, Canada is the story of fifteen-year-old Dell Parsons, his twin sister Berner, their gregarious Alabama-born father Bev (“He never conceded that Beverly was a women’s name in most people’s minds.”) and their tiny, intense, bookish mother “Neeva Kamper (short for Geneva).” The novel’s commanding opening lines bear repeating: “First, I’ll tell about the robbery our parents committed. Then about the murders, which happened later.”

The Parsons arrive in Great Falls in 1956. It’s just another one of the many towns they’ve landed in due to Bev’s Air Force career. A veteran of B-25 bombing raids during World War II, Bev is anything but a conservative and settled-down military man. By the spring of 1960, Bev exits the Air Force after some of his less than admirable activities come to light. Set adrift, Bev makes one bad decision after another, until he ropes his wife into robbing a bank with him in order to settle a debt over a beef-smuggling racket he’s begun with some Cree Indians.

While Bev shoulders much of the blame for the Parsons family’s downward spiral, Ford manages to keep the oft oafish patriarch sympathetic. Bev is, after all, a thirty-seven year old with fifteen-year-old twins, a dissatisfied wife, and no idea how to function in the real world—he’s lived in the bubble of military life since he was a teenager. Ford mines that grey vein where fiction thrives.

But this is not Bev’s book. No, even as Bev’s actions propel the plot, it is young Dell’s observations, earnest voice, and struggle to make sense of life that shape and make Canada so compelling. When Dell offers a bit of observation laced with wisdom, it rings true and earned. The evening after his father decides to rob the bank, Dell believes he can see his father’s physical features shift: “He was becoming who and what he was always supposed to be. He’d simply had to wear down through the other layers to who he really was.”

Ford once told me, “I try to connect emotions to experience in a way that is different from what convention tells us is true.” Indeed he does, and beautifully.

Ford’s prose in Canada is crystalline without being sterile. You can luxuriate in the writing, but also feel compelled to keep turning the pages as quickly as you can. This last compliment hinges on Ford’s steady, hypnotic rhythms and the repetitions in Dell’s storytelling. Canada constantly curls back on itself. It’s a haunting technique; I was reminded of the hypnotic cadence in the novels of Norwegian author Per Petterson (whom Ford has praised). There are similarities in Canada to the elegance and impact Petterson achieves in Out Stealing Horses.

Ford’s prose in Canada is crystalline without being sterile. You can luxuriate in the writing, but also feel compelled to keep turning the pages as quickly as you can. This last compliment hinges on Ford’s steady, hypnotic rhythms and the repetitions in Dell’s storytelling. Canada constantly curls back on itself. It’s a haunting technique; I was reminded of the hypnotic cadence in the novels of Norwegian author Per Petterson (whom Ford has praised). There are similarities in Canada to the elegance and impact Petterson achieves in Out Stealing Horses.

Ford has the confidence to title a novel Canada, then take the reader to page 213 (in a 418-page book) before Dell sets foot in desolate Saskatchewan. Throughout, the pacing trudges forward methodically, entrancing the reader; one of Ford’s long-held skills is that he is a technically gifted writer, still capable of honest storytelling.

An elegant nuance abounds. Here, in a moment when Dell’s twin, Berner, runs away to San Francisco rather than move north with her brother, Dell looks back from his sixties to his fifteen-year-old self:

To concentrate on Berner leaving would make all this seem to be about loss—which isn’t how I think about it to this very day. I think of it as being about progress, and the future, which aren’t always easy to see when you’re so close to both of them.

The subtle layers of Dell’s memory, his adult opinion and his recalled youth, give Canada the melancholic patina of a settled thing. The life on the page has been lived, but we still race on to figure out the how and why of it.

“Bad things come to everybody,” Ford once wrote. “We don’t get out of it. But the real important, the real interesting, optimistic side of all bad things, is what we do in consequence of them.”

In some ways, that might serve as a thesis statement of sorts for Canada. In the end, the weight of Canada lies in the cumulative effect of many small decisions that went one way but could have gone another—in other words, the consequence of life.

Ford with dog. CR: J. Bodwell

Ford with dog. CR: J. Bodwell

Further Links & Resources

- A brief excerpt from Canada at McLeans.ca

- Richard Ford speaks with NPR’s Diane Rehm about the book.

- An interview with Richard Ford at The Guardian

- “Nobody’s Everyman,” an essay about Ford’s recurring character, Frank Bascombe, at Bookforum