Maria Romasco Moore grew up collecting antique photographs, the kind of discarded family pictures you find packed into crumbling shoeboxes at flea markets and estate sales. She describes the enchantment of opening an ancient Whitman’s Sampler at a flea market and finding something better than chocolates: her first payload of long dead strangers, writing, “I spent many evenings looking through the images, staring at the faces of the people in them, trying to guess their stories. The box was like a mystery novel, written out of order and without a single word.” Years later, this need to resurrect the abandoned dead brings us her novella-in-flash, Ghostographs: An Album (Rose Metal Press). The linked stories chronicle an unnamed narrator’s childhood in a town populated by haunted dogs, people growing from a field like sunflowers, children dropping pennies into a bottomless abyss, and a father who fishes for ghosts in a river that sometimes turns to molten glass, sometimes to milk.

The thing about Ghostographs is that you’re never really sure what’s real. Is the narrator recalling a childhood in a town in which dream logic rules the day, or are these just childhood games and dreaming writ as reality and relayed without the usual wink? Part of the genius of Romasco Moore’s writing lies in its refusal to provide a clear answer. In this way, it opens the door to that childhood space, somewhere between the imagined and the real, which fantasy and sci-fi novels can never truly access. Those genres are rule-bound: the worlds they spin need to make sense. Romasco Moore’s world isn’t tied to sense-making but to desire. Do you want the abyss to be real? Then it’s real.

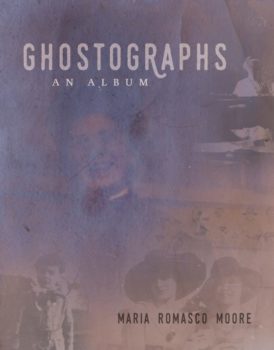

Each flash piece in Ghostographs is accompanied by an antique photograph from her personal collection, most of which appear to date from the early 20th century. Women in high-necked, long-skirted dresses squint into the sun. An old man and a young boy stand in an abundant garden, appearing to sing hymns to sunflowers. Pre-teen boys and girls dressed all in white kneel in front of a cluster of trees, on the verge of bursting into laughter. In each picture some detail—a slant of light, the quirk of a mouth—evokes an eerie strangeness, which Romasco Moore picks up and spins into a tale about wild packs of children, a woman with snakes for veins, and plants that must be prayed over if they are to grow toward God.

Each flash piece in Ghostographs is accompanied by an antique photograph from her personal collection, most of which appear to date from the early 20th century. Women in high-necked, long-skirted dresses squint into the sun. An old man and a young boy stand in an abundant garden, appearing to sing hymns to sunflowers. Pre-teen boys and girls dressed all in white kneel in front of a cluster of trees, on the verge of bursting into laughter. In each picture some detail—a slant of light, the quirk of a mouth—evokes an eerie strangeness, which Romasco Moore picks up and spins into a tale about wild packs of children, a woman with snakes for veins, and plants that must be prayed over if they are to grow toward God.

It’s tempting to call Ghostographs enchanting, but that’s quite not the right word—there’s a certain cuteness implied by “enchanting,” a princess-y sparkle attached by generations of Disney movies—and Romasco Moore’s collection is too stark and sad to sparkle, pervaded as it is by loss and little jolts of horror: if this is a fairy tale, it’s the old-school kind, in which girls dance all night in slippers full of blood because they’ve hacked away their own toes. Still, I was enchanted by Ghostographs: reading it made me remember the strange games children sometimes play, flirting with danger and death to see how they taste. Pretend the waterfall is haunted, the children tell each other. Pretend Tess is invisible. Pretend the river is a bottomless pit. And they pretend so hard that maybe everything they pretend comes true.

Romasco Moore’s work possesses a sharp sense of childhood, an incisive respect for the way kids understand the world and the mechanisms they employ to control their lives. This isn’t limited to make-believe. Children can be savage and destructive, and the author’s work touches on the nuanced logic behind this violence. In “The Troublemakers,” she writes:

…we were all troublemakers sometimes. It came on like a fever—the urge to wreak havoc, the desire to manufacture disorder. The need to take ahold of some small piece of the world and then move it—ever so slightly—out of place. To reaffirm in this manner the baffling fact of our own existence, tenuous and ephemeral as an unwatched crystal bowl….To prove to the world that we mattered, that we were there once, scissors in hand, and that afterword everything was different…

Ghostographs celebrates the fundamental honesty of our urges toward wildness and fantasy. This was your world once too, it says. Remember?

I think this is what Ghostographs wants from its readers: remembrance. While much of the book is about the wild dreamscape of childhood, in the end the story is about the end of a time and place. Ghostographs has a gently elegiac feel. As the narrator grows and changes, so does the community, until eventually the town and the people in it become unrecognizable. The narrator mourns this loss, saying, “There is a new town where the old one used to be. There are new houses, new roads. They look the same as the old ones, but they are new.”

I know the feeling—a disorientation you can’t quite put your finger on, a home that feels like a reflection of the place you used to live. Romasco Moore grew up in Altoona, a southern Pennsylvania town about two hours outside of Pittsburgh, the city where I’ve spent most of my life. There’s a feeling, in this quadrant of the state, of change rushing ahead, an accompanying sense of loss you can’t fully articulate or justify. There are the things you can be angry about for a good reason: the displacement of families who’ve lived in one place for generations, the fact that no one in your age can afford a home. But how do you explain that one of the things that breaks your heart is the loss of decay? That when passing the chic new coffee shop, you miss the abandoned storefront it used to be, miss the way the light slanting across its faded blue windowsills looked like the memory of water? I’m not trying to romanticize poverty or say that revitalization is all bad. What I’m saying is, change is complicated. What we call progress often erases a stark, haunted beauty that can’t be approximated by any amount of artfully distressed paint or lovingly curated clutter. That in growing, we leave behind something ephemeral and lovely that we can never regain.