When Della Brown was growing up in the 1950s and 60s, young, working-class women had few career options. Many became secretaries, aiding and abetting male bosses in the business world. Others waited tables or became assistants in medical facilities or schools. Still others, whether by default or by decision, became homemakers and moms, a limited role that helped kick-start a late 20th century feminist revival.

Although Della was well aware of the constraints on her gender, she was not thinking politically when, in 1968, at the age of eighteen, she enlisted in the U.S. Army. Instead, she was being pragmatic. Uncle Sam would pay for her to become a registered nurse, a career she considered far more challenging and interesting than typing, filing, waitressing, or assisting. The catch, of course, was that the scholarship required a post-completion year of service overseas. It would be an adventure, she thought, a chance to get out of tiny Sterling, New York and see something different and new.

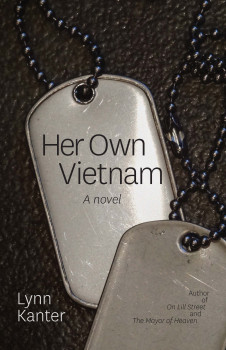

“I expected to go to Japan or the Philippines, where they were evacuating casualties from the war,” she explains years later to her younger sister, Rosalind, in Lynn Kanter’s intense and gripping third novel, Her Own Vietnam (Shade Mountain Press). “They told us nurses had to volunteer for the war and there was already a long waiting list.”

Alas, this was untrue: immediately after completing basic training, Della was shipped to Southeast Asia and catapulted into a war zone. Kanter’s account of her protagonist’s time in country is graphic, and the chaos of an undersupplied operating room is vividly rendered. The wounded, for the most part young men whose lives had not yet taken shape, haunt Della, and more than three decades after returning to the States fuel her nightmares and post traumatic stress. Kanter’s descriptions evoke the pooling blood and amputated limbs that formed the fabric of Della’s everyday efforts. What’s more, periodic flashbacks make clear how hard it is for veterans to put the past behind them.

Indeed, barely a day goes that Della does not remember the horror:

For twelve hours a day, six days a week, the ICU and the doctors, nurses, and corpsmen who inhabited it were Della’s universe. Hour after hour she replaced dressings saturated with pus and blood. She clamped chest tubes and emptied glass suction bottles that were filled, in ghastly shades of yellow, pink, and white, with fluid from men’s lungs. There was no time to stop, to rest, to eat.

Small wonder that upon returning to the U.S., Della barely speaks of the ordeal or tells family or friends what it was like to nurse combat casualties. They did not ask, she says, so she did not tell.

“They clamored to hear about flirtations and romances,” Kanter writes. “But anything real they recoiled from. Anything gory or wrenching they did not want to know. And Della had nothing to tell them that wasn’t wrenching. She had brought back no pleasant souvenirs from the bloody borderland of life and death.”

Although Kanter herself did not serve in Vietnam, she spent years interviewing women who did and learned that many female veterans kept silent about their military experiences once they returned home. The facts she gleaned—about being near combat and treating the injured only to return them to the battlefield—clearly informs Her Own Vietnam, but the novel never feels preachy or didactic. In fact, factual data about the war—and about the brave women who volunteered to provide medical care to the more than 303,000 American men who were injured and 58,000 who died—is seamlessly woven into a story that touches themes as wide-ranging as mother-daughter conflict, parenting, divorce, alcoholism, friendship, forgiveness, sibling rivalry, Post Traumatic Brain Disorder, and military bombast. It’s a potent brew—a book I wish every kid being cajoled by military recruiters would read before signing on the dotted line and committing to fight.

That said, Her Own Vietnam highlights the blood, guts, and senseless loss of life endemic to all wars without ever explicitly addressing the folly of U.S. involvement in Indochina. Likewise, the book says nothing about the Cold War, the fight against communism, or what the U.S. government was hoping to accomplish by sending troops to the region. And that’s okay since the point of Kanter’s unsettling book is that war will never solve the world’s political, economic, or social problems. In fact, Kanter treats the arguments used to justify the carnage of war as a distraction, unworthy of attention. What’s more, she eschews political cant in favor of humanism.

That said, Her Own Vietnam highlights the blood, guts, and senseless loss of life endemic to all wars without ever explicitly addressing the folly of U.S. involvement in Indochina. Likewise, the book says nothing about the Cold War, the fight against communism, or what the U.S. government was hoping to accomplish by sending troops to the region. And that’s okay since the point of Kanter’s unsettling book is that war will never solve the world’s political, economic, or social problems. In fact, Kanter treats the arguments used to justify the carnage of war as a distraction, unworthy of attention. What’s more, she eschews political cant in favor of humanism.

All of this, however, is subtext, and Della’s story is told with tremendous attention to detail. The novel paints an intimate portrait of her psychological suffering—and it is not a huge leap to understand that her pain has been felt by far-too-many returning veterans, both male and female.

Della reveals the depth her own angst during a conversation with her ex-husband, another Vietnam vet. Sure, she confides, since returning home she has been able to hold down a demanding nursing job, maintain relationships with friends and family, and parent their daughter, but of late, she has increasingly been triggered by random sounds, sights, and smells. The upshot, she continues, is that she feels as if she is coming unhinged. “I’m being overrun by memories,” she tells him. “It makes me feel kind of sick, like there’s all this fear and guilt churning around, eating away from the inside.”

It’s a horrible confession, reflective of the retrospection—and introspection—that consumes much of Kanter’s novel. Nonetheless, it beautifully elucidates the trauma of post war re-entry, a distinction that separates Della from aging Baby Boomers who have never seen combat.

Like most of us, Della has to grapple with past and present concerns, burdens, and ghosts, yet it is the traumatic aftereffects of her military service that sets her apart. Now middle-aged, Della is wrestling with the lingering baggage of paternal abandonment alongside recurring dreams about dying soldiers that jolt her out of sleep with alarming regularity. As if this were not enough, an out-of-the-blue letter from her best friend in Vietnam, a woman she has not seen or heard from in thirty years, has upended her life and sent her reeling. It is also the narrative hook that unveils Della’s past and that allows Kanter to offer retrospective insights on the difficulties of post-war adjustment, for while the story is set in the here-and-now, the past intrudes with dramatic force.

In Della’s case, when the delusions start, she is knocked sideways, and then some. She is at work in the oncology unit of her local hospital when she suddenly thinks she hears the sound of low flying helicopters “swooping down to deliver its bloody cargo of other mothers’ sons.” Her present-day coworkers come to the rescue and take her home, but this only convinces Della that she is, indeed, going crazy. “So it was official: Della was losing it…It was not something she could ignore. She couldn’t be relied on to run through the nurse’s traditional five rights: Right patient, right drug, right dose, right method, right time—while her mind was busy replaying the greatest hits from 1969.”

In Della’s case, when the delusions start, she is knocked sideways, and then some. She is at work in the oncology unit of her local hospital when she suddenly thinks she hears the sound of low flying helicopters “swooping down to deliver its bloody cargo of other mothers’ sons.” Her present-day coworkers come to the rescue and take her home, but this only convinces Della that she is, indeed, going crazy. “So it was official: Della was losing it…It was not something she could ignore. She couldn’t be relied on to run through the nurse’s traditional five rights: Right patient, right drug, right dose, right method, right time—while her mind was busy replaying the greatest hits from 1969.”

But how to heal? Is recovery even possible? Needless to say, it wouldn’t be surprising to see Della simply crumple and fold. That she does not is testament to Kanter’s belief in human resilience. It’s powerful, if a bit too neatly resolved by conversation, confession, and a blatant reminder that she needs to remain focused on what is ahead.

Kanter’s more general contention, however, is anything but neat or simple. By implication, she suggests that it is only by truly listening to those who have been to war—by prodding those who have seen first-hand what it is like to be surrounded by death, putrid rot, and decaying flesh—that we can commit ourselves to finding non-violent solutions to the problems that plague us. Her plea calls to mind anti-war activist A.J. Muste’s [1885-1967] declaration, “There is no way to peace. Peace is the way.”

Her Own Vietnam underscores Muste’s words—and is a cogent rebuttal to politicians who wax poetic about the glory and honor of war and militarism.