There are two trees in my front yard–an oak and a beech–that have grown together, their trunks no longer two but one. My ten-year-old named them Romeo and Juliet. She’s outgrown the fairytales of Disney and Grimm, and though she doesn’t know the complicated and tragic end of Shakespeare’s play, she does know that it is a more grown-up kind of fairy tale, one that could begin with the line: “Once upon a time, there were two people who couldn’t live without each other, but something went terribly wrong.”

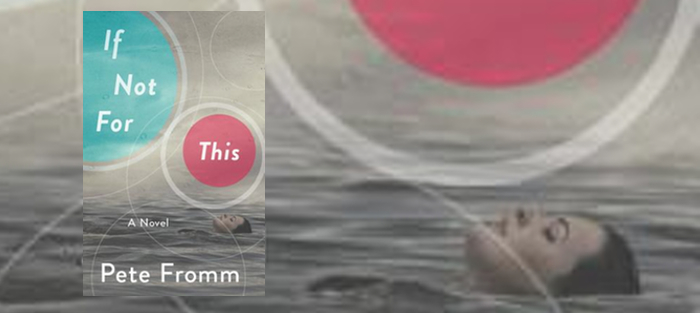

Pete Fromm’s third novel, If Not For This (Red Hen Press), is a fairy tale in this vein: equally an epic love story and a devastating tragedy. We meet both Maddy and Dalton in the prologue, well into their marriage, and Maddy well into the clutches of multiple sclerosis. They draw stares–Maddy confined to her wheelchair, struggling with the ability to speak, twitching, arm shaking, while Dalt (who Maddy describes as “the original idea for Michelangelo’s David”) pushes her. She snaps at the gawkers, “This is nothing. You should see us in bed.” In this one-page glimpse of their future, it is a metaphor for their lives that, in handling the wheelchair, Dalt takes on the practicality of her deteriorating condition while Maddy, in her own words, “dare[s] this all to be nothing.” It is also where she marries her greatest hope—that this fairy tale will have its happy ending—with her greatest fear—that tragedy will overpower it.

Though the prologue briefly flashes forward, If Not for This really begins where Maddy and Dalt begin, the edge of Wyoming’s Snake River where both live as river runners. The boatman’s bash where they meet would feel cliché–the party with its kegs and red Solo cups and flirting over music too loud–if not for the very authenticity of that cliché, because you’ve been exactly there, and when Dalton offers to take Maddy on a moonlight ride in his raft, it doesn’t end predictably. She is, after all, the self-proclaimed “ice queen,” the one who doesn’t want to be tied to anyone, anywhere. But there’s another float after that, and a day of skipped work to watch the lightening roll in, and the chemistry between the two is so taut you could hang their discarded clothes off it.

Somewhere in the sparse dialogue and lyrical prose, we realize before Maddy does that this is no ordinary romance, making her realization just a footnote to our own: “In the history of time, no two people have ever been this close. I know this like I know gravity.”

Lines like these could potentially elicit an eye-roll. But when Maddy’s voice, which is otherwise crisp, pragmatic, and often humorously sarcastic, lapses on these early pages into the dreamy language of one falling in love, we forgive the sentiment because it feels earned. And, more importantly, because the tale is told looking back with the full knowledge of what will eventually unravel. When they marry in the shadows of the Tetons and Maddy marvels that “the paths of the Buffalo and the Snake lay clotted with mist, like billowed white highways we floated away on…Dalt and I taking our first strokes toward happily ever after,” we already know from the prologue this will be no happily ever after, at least in traditional terms. And we know that she knows this, as well, in the telling of the tale. Yet, still, we want to believe with her. We want to suspend our disbelief right alongside her, if only temporarily. In a fairy tale world, at least those of Walt Disney, the scene would cut to credits and we’d go to bed assured of the unbreakability of Maddy and Dalt. Instead, we are still at the start of their story, only the middle of chapter two, and it will be a long slow fade to black, Dalton and Maddy on a path as wandering as the river they run.

It can be no mistake that Fromm begins this tale against the backdrop of some of the widest, wildest land in the U.S. The intertwined futures of Dalt and Mad look just as wide and wild, their “strongest desire” to love each other, to live out their dreams of running their own river-touring company with the patter of little feet, and little else. Reality crushes in on them, though, finances driving them out of their home and off the Wyoming rivers. They settle in Oregon, instead, in a little house in the suburbs, the dream of family and owning their own business still in bloom until Maddy is slammed with the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. As the disease takes its toll on Maddy physically, the elbow room around her mirrors the increasingly confining disease: the wilderness to suburbs to house to wheelchair an outward expression of her struggles with the narrowing of her personal loss of use of her body, from the freedom to walk to the use of her hands, to language, to even swallowing.

It can be no mistake that Fromm begins this tale against the backdrop of some of the widest, wildest land in the U.S. The intertwined futures of Dalt and Mad look just as wide and wild, their “strongest desire” to love each other, to live out their dreams of running their own river-touring company with the patter of little feet, and little else. Reality crushes in on them, though, finances driving them out of their home and off the Wyoming rivers. They settle in Oregon, instead, in a little house in the suburbs, the dream of family and owning their own business still in bloom until Maddy is slammed with the diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. As the disease takes its toll on Maddy physically, the elbow room around her mirrors the increasingly confining disease: the wilderness to suburbs to house to wheelchair an outward expression of her struggles with the narrowing of her personal loss of use of her body, from the freedom to walk to the use of her hands, to language, to even swallowing.

The devastating diagnosis comes on the heels of the joyful news that Maddy is finally pregnant, introducing the first crack in their happily ever after. The ameliorative effects of pregnancy on the symptoms are like a magic potion, bringing Maddy to her old self: energetic, capable, independent. After their son is born, Dalt, enthralled at the idea of both more children and a healthier wife, even if only for nine months, pleads with Maddy to consider another baby, a baby she knows she “cannot hold…cannot lift out of the crib when she cries” once the pregnancy hormones are gone.

It is not just Maddy who suffers, however. Although the story is told from Maddy’s point of view, the power lies not in how MS ravages her body but in how it ravages everyone around her, Dalt in particular. His hopes and dreams are, after all, intertwined with hers, and the loss of each freedom of Maddy’s is a loss equally his. Unlike Maddy, though, Dalt does not fight the changes that come. Instead, he sees it his duty to prepare for each new difficulty, an effort that infuriates Maddy, who is determined to deny it is happening even as she thinks twice over the safety of cradling her own baby.

The intensity of their love at first seems to be unshakeable, but Dalton’s need to care for and protect Maddy when she most wants to pretend all is fine for the sake of the family is what threatens to undo them. There is no fairy godmother here to rescue them, no apothecary to offer an escape, and the reality of life begins to fray their edges. Though Dalt rarely complains, it is clear the responsibilities of job, finances, kids, and an often-helpless (although stubborn) wife drain him. As the effects of MS demand more of Dalt, Maddy offers him the only thing left she has to give: freedom from her. In a world of literature where relationships fail because love diminishes or is diverted, Fromm creates characters who love each other too much, a heartache far more devastating than any other, for both the characters and the readers.

The intensity of their love at first seems to be unshakeable, but Dalton’s need to care for and protect Maddy when she most wants to pretend all is fine for the sake of the family is what threatens to undo them. There is no fairy godmother here to rescue them, no apothecary to offer an escape, and the reality of life begins to fray their edges. Though Dalt rarely complains, it is clear the responsibilities of job, finances, kids, and an often-helpless (although stubborn) wife drain him. As the effects of MS demand more of Dalt, Maddy offers him the only thing left she has to give: freedom from her. In a world of literature where relationships fail because love diminishes or is diverted, Fromm creates characters who love each other too much, a heartache far more devastating than any other, for both the characters and the readers.

Even with the ravages of MS, the small and great losses of dreams, the scraping of hope against fear, the true fairy tale is in the voice of Maddy who, even in the most heart-crushing scene of life crumbling around them, calls herself and Dalt “the lucky ones.” The miracle that Fromm pulls off is that, despite the devastating toll of MS, or maybe even because of it, we might believe they are.

We’ve discovered this month that the oak tree in our front yard is dying and that the beech, while healthy now, has become so conjoined that it, too, is facing imminent death. There is no way to separate one from the other, no way one can draw enough strength from its own roots to feed the other. They are just trees, we tell our daughter, who is distraught over the news. “But they are special,” she says. “They love each other.” She is learning one of the harder lessons of life: true love has a cost, even in fairy tales.

True love with a cost may be Pete Fromm’s calling card, his stories peppered with characters who inhabit broken places. But even though Fromm is a four-time winner of the Pacific Northwest Booksellers Literary Award for two novels, a memoir, and a short story collection, I predict If Not For This will be the book to catapult him into a greater national spotlight. This “fairy tale with a tragedy” will make you want to stretch your muscles and feel their pull, to breathe in great gulps of air, and to love with the same kind of tenacious determination Maddy expresses at the start:

When I have to catch my breath, find something to convince me we’ll always have enough to go on, I reel back to my anchor point…And the air I breathe gets all rarified even now, remembering how stunned I was, how hardly daring to believe. I can’t quite swear I believe it yet, believe we’ll last through even this.