Subjects choose authors, and Fallingwater chose Kelcey Parker. Describing her first visit to the architectural icon in her author’s note to Liliane’s Balcony, A Novella of Fallingwater (Rose Metal Press, 2013), Parker writes: “By the time the tour was over, I knew two things: I had to write about this place, and the story would be a domestic tragedy. What I did not know was that a domestic tragedy had already occurred there.” Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater as a weekend retreat for Pittsburgh department store magnates Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann; the tragedy Parker intuited was the Kaufmann’s difficult marriage. Over the course of her research she discovered Edgar Kaufmann’s love letters to Liliane, and returned to the house to work as a guide. She knows house and story from the inside out. Parker says in an interview with Talking Writing, “Wright leads you through space and sounds and organic substances that you’ve never experienced in a house. (And isn’t that akin to what writers aspire to with fiction: leading readers through narrative space?)”

Subjects choose authors, and Fallingwater chose Kelcey Parker. Describing her first visit to the architectural icon in her author’s note to Liliane’s Balcony, A Novella of Fallingwater (Rose Metal Press, 2013), Parker writes: “By the time the tour was over, I knew two things: I had to write about this place, and the story would be a domestic tragedy. What I did not know was that a domestic tragedy had already occurred there.” Frank Lloyd Wright designed Fallingwater as a weekend retreat for Pittsburgh department store magnates Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann; the tragedy Parker intuited was the Kaufmann’s difficult marriage. Over the course of her research she discovered Edgar Kaufmann’s love letters to Liliane, and returned to the house to work as a guide. She knows house and story from the inside out. Parker says in an interview with Talking Writing, “Wright leads you through space and sounds and organic substances that you’ve never experienced in a house. (And isn’t that akin to what writers aspire to with fiction: leading readers through narrative space?)”

A successful novella, like this one, uses to advantage the tensions inherent in its sustained brevity as neither story nor novel. Parker leads us through a compact narrative space composed of brief linked soliloquies that press the boundaries between poetry and fiction. Multiple voices—Liliane’s, Edgar’s, Frank Lloyd Wright’s, and those of present day visitors on a tour—speak in deeply interior flash chapters sometimes only a paragraph long. Liliane’s Balcony is, like its architectural inspiration, an intentional structural experiment. The author’s note describes Fallingwater as a “novella-sized house” and the formal structure of this work as “analogous to that of Fallingwater.” She explains that just as the house’s stone chimney “serves as the vertical core, supporting the rest of the house, Liliane’s story serves as the book’s core.” And just as the actual balcony at Fallingwater links exterior and interior space, here the transitional balcony zone serves as the bridge between the external and internal experience of her characters, the negative space Keats describes as “made for the soul to wander in and trace its own existence.” For above all, beyond subject, form, and genre, Parker’s novella is most interested in exploring the impact of external architectural space on inner psychological experience. Underscoring this motif, the book opens as Liliane stands on her balcony:

She is at the farthest edge of the house. Her white linen gown flaps in the wind, and a September chill reaches up and grabs her legs. One question she has always pondered: if one is on the balcony, is one inside or outside? The breeze says outside. But the balcony is not an exposed rock’s edge; it’s part of the house, designed by the architect. Behind her is her room, its warm glow. The French doors are open and the light spills onto the stone patterned ground. The architect had been so clever at dissolving the boundaries of the two.

Liliane is at home neither in her house nor her life, emotionally trapped on a psychological precipice, neither in nor out of her marriage. She can no longer maintain her precarious balance. The fatal dissonance between the illusory surface of her life and her internal experience comes to a crisis on the balcony: “It is the contrast between the inside and the outside that she can no longer abide.” And so throughout the book, the balcony zone of intermediate, indeterminate space serves as both stage and crucible for internal intra-psychic dramas. Suspended mid-air between heaven and earth, above the invisible but audible falls, each of Parker’s characters, Liliane and the present-day tourists, confronts transformative, undeniable internal conflict.

Fallingwater’s balcony is the most provocative and theatrical space in a daring house designed by a dramatic architect. It recently served as the literal stage for an outdoor production of “Shining Brow,” an opera based on a tragic scandal in Frank Lloyd Wright’s life. The magical cantilevered balcony appears to float, a sculptural masterpiece, as well as an architectural one. However, dramatic sculpture is not necessarily great engineering. The stress of defying gravity, the illusion of weightless counterpoise, has caused serious structural strain, and the resulting cracks have had to be repaired recently at great expense.

Parker’s work is similarly daring, and provides much narrative and aesthetic delight, but also at some risk and expense. She deftly captures the sensations of visiting the house—both the demands of its narrow stairs and low ceilings and its rewards of light and color and the sound of the invisible falls beneath. The author also nails my own, apparently typical, semi-comic experience of encountering this awesome domestic Shinto temple accompanied by a party of ill-assorted pilgrim tourists. However, the multiplicity, brevity, and flash pace of her visitors’ impressions and stories flood the reader. The author may intend to inundate with a cascading waterfall, like the falls of Bear Run beneath the house. But in such a concentrated span of pages perhaps less might have been more, as another architect has said.

For ultimately, as Parker herself says, Liliane’s story is the core, and the one that most deeply engages the reader. Liliane and her house above the falls are inextricably intertwined, in the deepest way. She is her house; and in this the reader is reminded of Mrs. Ramsay and her island home across the water from the beacon in Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse. Both works are meditations on love, loss, time, and change. But while the Ramsays’ story ends in loss, as all love stories finally must, something ineffable and good endures. Parker’s prose, like Woolf’s, is luminescent, but the resultant story is darker and more bitter. Liliane’s tragedy reveals the cost of the pursuit of aesthetic perfection, the dissonance between appearance and reality, and the cracks that appear over time beneath surfaces.

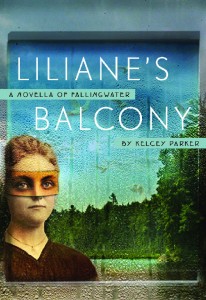

Parker herself is keenly attuned to aesthetic questions, the intersection of art and practice. Director of the creative writing program at Indiana University – South Bend, she describes herself to Talking Writer as “particularly drawn in by the tensions between the book as object…and the transition to digital reading machines.” She teaches narrative collage, a combination of image and text, and chapbook design. Her sensibility is well supported by her publisher; Rose Metal Press is committed to producing beautiful books-as-objects, and this is one. Ornamental linear designs by Frank Lloyd Wright underscore each chapter heading, and frame the page numbers. Even the typeface is based on an alphabet Frank Lloyd Wright designed.

These spare pages please and engage the eye, heart, and mind, like leaves in a chapbook. Liliane’s Balcony is a small elegant book in every way. Readers will be inspired to visit Fallingwater and listen for Liliane’s voice above the falls.