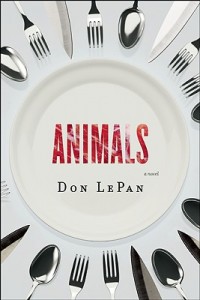

What are the ethical implications of eating factory-farmed meat? This is just one of the questions that Don LePan’s novel, Animals (Soft Skull, 2010), addresses on a fictional—yet existentially relevant—level.

What are the ethical implications of eating factory-farmed meat? This is just one of the questions that Don LePan’s novel, Animals (Soft Skull, 2010), addresses on a fictional—yet existentially relevant—level.

What makes humans different from or even superior to animals? To what depths of love and cruelty can a human heart succumb? As we follow LePan’s characters into a not-too-distant future, where (SPOILER ALERT) human beings are slaughtered as edible products–much like their farmyard brethren–LePan’s descriptions of suffering in the feedlots may rouse our sense of injustice. Yet every day we pick up our knives and forks to consume beef, chicken, and pork, we allow this very same suffering to occur in our own world.

Scientific facts are woven throughout LePan’s dystopian novel, often in the form of footnotes created by the character Broderick, who is re-telling the story at a distance, and this blending of truth and literary license raises some interesting questions. For instance: As modern food supplies continue to dwindle in nutritional value, and we pump our animals full of hormones or feed them inappropriate diets in order to fatten them for the slaughter, what becomes of the old saying “You are what you eat”? In LePan’s world, it mutates to “Garbage in, garbage out”: consuming food that isn’t really food results in birth defects. And these birth defects become so overwhelming a problem that people find it simpler to classify those with significant defects as “non-human,” sending them off to become food for the humans that remain. What, then, separates humans from animals whose only motto is “eat or be eaten”?

Some of the book’s characters display compassion and understanding for these dehumanized “mongrels” (LePan’s term), but most do not. The character most concerned with their plight is a young girl, Naomi, who cannot grasp the enormity of the situation but who nevertheless strives to rectify it. LePan suggests that although we know that factory farming is inhumane, we remain complicit by doing nothing to prevent it; as we continue to create food “products,” rather than actual food, we distance ourselves further and further from the filthy, dangerous floors of the slaughterhouse. In doing so, we provide ourselves an excuse for our inaction against dangerous, greedy corporate giants, and we also allow ourselves to become weaker human beings. LePan’s rhetoric hopes to sway us to take up the fight outlined in his predecessor Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation.

Though the book is often academic in tone (befitting LePan’s status as the founder of an independent academic publishing house), the story of mongrel Sam and the family that adopts him as a pet appeals to readers of fiction, challenging perceptions of right and wrong, good and evil. Who is to blame? Sam’s mother, who cannot care for her child and leaves him on the doorstep of a wealthier neighborhood family? The system that denies her access to healthcare, which would have identified her “mongrel” son as deaf rather than less-than-human? Or each and every person who over-consumes meat? In posing these questions, LePan’s novel asks the meat-eating reader to examine his or her own complicity in the factory-farming system.

Extras

- Read the beginning of Animals here, and shop for it at your local indie bookstore.

- Interested in further exploring the issues raised by this novel? LePan discusses them on his blog. He also provides an alternative ending to the book on his website.