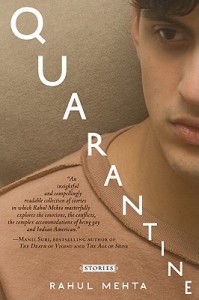

In his debut publication, Rahul Mehta confounds reader preconceptions. Mehta’s short story collection, Quarantine, features a cast of homosexual Indian-American men. The book artfully interweaves sexual and racial tensions without resorting to tropes or creating an antagonistic “other.” In the title work, “Quarantine,” both the gay, American-born narrator and his traditionalist grandfather experience the isolation metaphorized by the story’s title. The two generations simultaneously search for belonging, prompting the older man’s plea to stay among the Hare Krishnas. Decrepit for most of the tale, grandfather Bapuji finally comes to life among the devotees, “leading the aarti, chanting ‘Hare Krishna, Hare Ram.’”

In his debut publication, Rahul Mehta confounds reader preconceptions. Mehta’s short story collection, Quarantine, features a cast of homosexual Indian-American men. The book artfully interweaves sexual and racial tensions without resorting to tropes or creating an antagonistic “other.” In the title work, “Quarantine,” both the gay, American-born narrator and his traditionalist grandfather experience the isolation metaphorized by the story’s title. The two generations simultaneously search for belonging, prompting the older man’s plea to stay among the Hare Krishnas. Decrepit for most of the tale, grandfather Bapuji finally comes to life among the devotees, “leading the aarti, chanting ‘Hare Krishna, Hare Ram.’”

Finding these unlikely correlations between worlds, Mehta blurs cultural distinctions in the hyphenated Asian-American identity. In “Ten Thousand Years,” he sees Hindu lore in a Western relationship. The narrator recalls a poem in which Kali straddles the corpse of Lord Shiva, aligning the act with his lover’s infidelity: “Kali was fierce—a string of severed heads around her neck, her blood-stained tongue exposed, machete drawn as she lowered herself upon Shiva’s dead, but erect, penis.” The protagonist likens that image to “[his lover] and Miss Andhra Pradesh taking turns practicing corpse pose in the sand.”

Mehta’s simple yet striking imagery becomes most effective in “The Cure” and “What We Mean.” Situated in the middle of the book, the stories provide brief repose from Mehta’s predominantly character-driven works. Instead, Mehta uses these pieces to showcase his mastery of language. “What We Mean” considers the varied manifestations of meaning: “When… dogs bark, they are trying to communicate something vital. Someone is trapped in a burning house… Someone is holding onto a branch in a fast-flowing river heading for a waterfall, the branch about to break.” Though they lack the driving plot of the surrounding stories, these pieces command reader attention through spare, evocative language.

Ultimately, Quarantine becomes less a meditation on sexuality and race and more an investigation of human connections. While the collection does not shy from sex, it also marvels at the restorative effects of platonic touch. In “Ten Thousand Years,” the narrator’s boyfriend, Thomas, forms a deeper connection with his grandmother than the grandson ever had. In Thomas’s touch, the elderly woman finds a tenderness her grandson could no longer give. She dozes to his “hand on her forehead, gently stroking it until she [falls] asleep.” Similarly, “A Better Life” explores the sympathies between a college graduate and the wife of his host family. Mehta’s gentle, emotional prose culminates in one of the collection’s most tender scenes when, wordlessly, Lala offers Sanj the only comfort she can through her embrace.