In a 1904 letter to Oskar Pollack, Franz Kafka wrote that “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.” L. Annette Binder seems to have taken this to heart. The fourteen stories in her debut collection, Rise (Sarabande Books), bring to mind the title of a Tom Waits album: Glitter and Doom. Rise contains a king’s ransom of both.

In a 1904 letter to Oskar Pollack, Franz Kafka wrote that “A book must be the axe for the frozen sea inside us.” L. Annette Binder seems to have taken this to heart. The fourteen stories in her debut collection, Rise (Sarabande Books), bring to mind the title of a Tom Waits album: Glitter and Doom. Rise contains a king’s ransom of both.

Pick up nearly any work of literary fiction these days and a reader would draw the conclusion that writers are a gloomy bunch; everything always goes wrong. Strains of fantasy, deformity (physical, emotional), the macabre, and plenty of bad (or absent) fathers run through Binder’s stories, but her writing elevates what, in the hands of lesser artists, would be mere gimmickry. It’s easy to see why Rise won the 2011 Mary McCarthy Prize.

The first story in the collection, “Nephilim” (which I’ve praised before), is perfect. A giantess (the back cover implies she had an angel for a father, but Binder rightly leaves this suggestion unresolved) falls in love with a young neighbor boy, decades her junior. “Falls in love” has come to narrow constraints in our society, but this story brushes them aside. So moving is the bond between Freda and Teddy that each reading only deepens the elegiac ending, “All beautiful things go away. Everyone knows this is true.” That arrow finds its hart.

Obsessives mask their brokenness and fear behind compulsive plastic surgery, a magic stone, and survivalist gear. Behold the damaged and the damned. These stories chop away at the frozen sea, with often-painful results. It’s a heavy burden on the reader, the seat in the confessional box full of people wanting absolution, protection, salvation that no number of rosaries will provide. The material grows so harrowing that “Dead Languages”—about an infant who only speaks ancient tongues and inhabits an isolated bubble of Etruscan, Dacian, and Elymian, cut off from his own mother—actually felt like a respite.

In “Tremble,” Leonard, a morbidly obese call center employee, falls in love with co-workers who resemble his dead mother. He describes the other end of his sales calls:

The widow who cried when he asked for her dead husband and the man who shouted about acid rain and mercury in the water. One old lady though he was her son. Freddy, you never call me anymore, she said. Don’t you love your momma? The babies wailing and the sirens through the line and all the people who cursed him for interrupting their supper. A man who laughed and laughed at the sound of Leonard’s voice. Maybe he was Armenian. Te zent tartakuti, he said, and it sounded like a curse.

May we never shout an expletive at a call center employee again.

The rarity of Binder’s moments of grace and humor give them great power and beauty. In “Nod” as Fish approaches his forty-third birthday—the year his father died suddenly in his sleep—he suffers insomnia. His wife hasn’t divined the cause.

He looked up from the catalogue then because she didn’t know. She lived with him in this tiny place, this third-floor apartment with its sloping floors, and they were mysteries to the other.

With a few deft strokes Binder conveys the crushing isolation of fear, one so dark and obscure it defies Fish’s abilities of articulation. But a few pages later, she lightens things with a remark about the wife, “She liked a steak every now and then, but at heart she was a vegetarian.” And Fish loves the imperfections his wife would hide: “Her front teeth overlapped a little, and her hair never stayed the way it should, and all these things she hated were the ones he loved best.” In “Galatea” a character remarks, “If we starve ourselves we can live forever.” We are bundles of contradictions.

With a few deft strokes Binder conveys the crushing isolation of fear, one so dark and obscure it defies Fish’s abilities of articulation. But a few pages later, she lightens things with a remark about the wife, “She liked a steak every now and then, but at heart she was a vegetarian.” And Fish loves the imperfections his wife would hide: “Her front teeth overlapped a little, and her hair never stayed the way it should, and all these things she hated were the ones he loved best.” In “Galatea” a character remarks, “If we starve ourselves we can live forever.” We are bundles of contradictions.

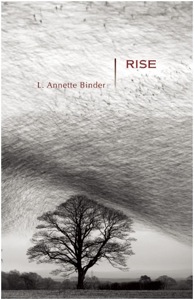

On the cover swarm a sea of small dark birds, caught in blurred motion so they resemble a thunderhead gathering over the plains. Binder can transform even the hopeful into a portent of doom, but the stories in Rise convey the utter darkness preceding the dawn with a clarity and precision that make even their pain a pleasure.

Further Links & Resources

- Read the title story of the collection – “Rise” – on Swink.

- Read “Ghost Girl” on Storyglossia.

- Convinced this is the deliriously dark collection for you? Pick it up from Amazon, IndieBound or Powell’s.