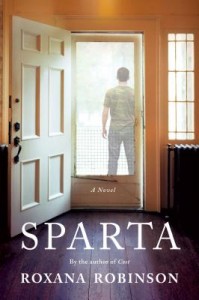

Roxana Robinson’s fifth novel, Sparta (Sarah Crichton Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux), tells of young Marine Conrad Farrell’s return home after two deployments in Iraq. It is the story of his struggle to readjust, to reconcile combat memories and present experience, to reconnect with his family and girlfriend. And though told primarily from his point of view, it is also the story of his family and his girlfriend as they struggle to understand his unspoken suffering.

Roxana Robinson’s fifth novel, Sparta (Sarah Crichton Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux), tells of young Marine Conrad Farrell’s return home after two deployments in Iraq. It is the story of his struggle to readjust, to reconcile combat memories and present experience, to reconnect with his family and girlfriend. And though told primarily from his point of view, it is also the story of his family and his girlfriend as they struggle to understand his unspoken suffering.

With the exception of Conrad’s occasional searing flashbacks to combat in Iraq, the novel takes place in territory familiar to readers of Robinson’s prior novels: upper middle class Manhattan and Westchester County. The Farrells are familiar also: sympathetic, thoughtful, fortunate, liberal intellectuals. Here once again the author plumbs below the surface to explore conflict and pain. The similarity in setting and cast with her previous novel, Cost (2008), is particularly close. Once again a child of privilege is in danger and his frightened family is trying to reach and rescue him. The threat in Cost was addiction, here it is the intangible dangers of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: depression, disillusionment, despair, dislocation.

The author, a Quaker, has said that her precipitating inspiration for Sparta was a story in the New York Times about the high incidence of traumatic brain injury among service men in Iraq, and the military’s apparent systemic disregard for prevention, protection, and after-care. She soon became intrigued with the experience of combat soldiers. Over the course of exhaustive research, including meeting with Marines and their families, she developed deep respect and compassion for the lives of these individuals and their family members, many of whom have also been deeply affected by the aftereffects of battle and conflict.

Robinson has also said that what intrigues her as a writer are “tangles…complexity.” And here as with her 2003 novel, Sweetwater, which focused on environmental degradation, she tackles a tangle of social and political elements and implications, dramatizing and humanizing the issue through the lens of individual experience. This is a political novel, inspired by the events in Iraq, and at home. But it goes far beyond. Eudora Welty once said, “Art is both more passionate and more dispassionate than reporting, and hence more true.” And thus Robinson renders the Farrells’ particular dilemma universal. In vivid, multi-sensory prose she describes the sand, the blood, the sounds of combat in Iraq through Conrad’s flashbacks, and all with the same close observation she bestows on her rich, painterly descriptions of domestic interiors, suburban and urban landscape, jogging, lovemaking, and family meals. The contrast between catastrophic memories and quotidian domestic life both conveys and more starkly outlines the returned veteran’s dismay and dislocation.

Yet while the Iraqi conflict is her proximate political inspiration, the deep literary inspiration of this book is the classical world. Specifically, the warrior state of Sparta in Homer’s Illiad. This is signaled immediately by her epigraph for the book, a quotation from Simone Weil’s The Illiad, or the Poem of Force: “The man who does not wear the armour of the lie cannot experience force without being touched by it to the very soul.”

Conrad, a Classics major at Williams, wrote his thesis on the Illiad. Burning with idealism, and wanting to test himself, he enlisted, to his family’s dismay, months before 9/11. The Illiad, he told his Iraqi translator and friend, is the greatest book in literature. But as a veteran he is consumed by anger and grief. Readers who enjoyed Madeline Miller’s The Song of Achilles and its exploration of the impact on Achilles of his beloved Patroclus’s death, will find much of interest in the way Robinson evokes the Illiad. Here, in structural as well as thematic homage to Homer, Robinson juxtaposes the consequences of battle on the warriors and their families at home. She interweaves the two experiences, as with Conrad’s flash of insight into his mother Lydia’s experience while he was deployed:

He thought of her here in the kitchen while he was gone, and he had a sudden sense of what it had been like. She had been here, moving through her day, waiting, waiting, for phone calls, waiting for letters, waiting for emails. Unable to do anything but wait. Waiting to learn once again that at that particular moment he was alive, still present in the world. He had been present to himself, living each second, but Lydia had been here in this silent house, powerless.

Robinson has said that her greatest discovery over the course of researching this book, and her hours of interviews with veterans, was that war is “about emotion.” She writes here of the emotional experience of war, and the emotional consequences on a returned warrior and his family. Her subject, like the Illiad’s, is fear, anger, death and survival, compassion and love. Robert Fitzgerald’s translation of the Illiad opens thus: “Anger be now your song, immortal one, Alchilleus’ anger, doomed and ruinous…” And anger, Conrad’s ruinous retrospective anger, is his immediate adversary and threat:

What made him so wild, what made his throat swell with rage, was the fact that no one here knew anything, no one here understood about the real world. No one understood what you looked for on the street (risk assessment), how you cleared a room (always moving as a team, though you had to slip through the fatal funnel one by one), how many shots you fired to kill someone (three), how you identified yourself on the radio (company, platoon, individual), how to establish a perimeter, or what the risks were in a room like this, filled with moving people and noise. They knew fuck-all here, everyone.

Throughout the novel, Conrad’s family invites him to talk about “it.” But he does not, he cannot. “He didn’t like being asked, though he didn’t like not being asked. He didn’t like scrutiny, though he also didn’t like invisibility.” Conrad considers exchanging email with his men as “still the main event of his day,” and he writes to one:

I know what you mean about finding it hard to talk about. I hardly talk about it at all. It’s hard being back and trying to think like a civilian.

Conrad’s emotional journey provides the intentionally spasmodic narrative arc here. He moves incrementally and intermittently through fear, anger, and grief. He advances and retreats; his family and girlfriend approach and retreat. They struggle, with compassion and love, to reach each other. This powerful book is riddled with authentic ambiguity and irresolution. Reading it brought to mind my own father, a veteran of World War II. His scarred back bore testimony to the wartime experience he never spoke of. He carried the memories buried deep as the remnant shrapnel until late in his life when he sought out the survivors of his company, to write and give voice to their experience (The Men of Company K, The Autobiography of a World War II Rifle Company, Leinbaugh and Campbell). Robinson is also the daughter of a veteran of that so-called great war. Her father also kept silent about his wartime experience, because, she believes, he could not communicate it.

Robinson dedicates Sparta “To those young men.” That simple dedication seems to include and recognize all the young men, of all the wars. Her dedicatory phrase resonates, reminding me of the young men Archibald MacLeish eulogized in Act Five and Other Poems (1948):

The young dead soldiers do not speak. Nevertheless, they are heard in the still houses: who has not heard them? They have a silence that speaks for them at night and when the clock counts. They say: We leave you our deaths. Give them their meaning. We were young, they say. We have died. Remember us.

With Sparta, Robinson remembers and honors the veterans and families of one war, and all wars. She speaks for her father and mine, for all the daughters and mothers, the sons and fathers.

Further Links and Resources:

- For more on Roxana Robinson and her work, please visit the author’s website.

- In 2009 the New York Times profiled authors about their writing spaces. Robinson was one of them. Check out where she writes. It might surprise!

- Listen to Roxana Robinson discussing Sparta on On Point earlier this summer.